How and why the Penn Museum relocated its iconic 25,000-pound ancient monument.

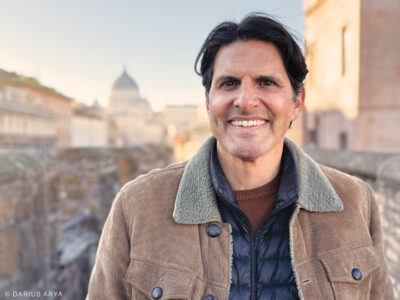

Surrounded by curious onlookers in the Penn Museum’s Mosaic Courtyard, Julian Siggers cranes his neck to watch what he calls “one of the most important objects in America from the ancient world” move for the first time in almost a century. “It’s a cocktail of exhilaration and anxiety,” the Penn Museum Williams Director says while a 3,000-year-old Egyptian sphinx glides across an elevated 200-foot ramp. “It’s one of those objects you can’t put a price on. It’s like hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars. But it’s made of red granite, so it’s very solid—which is reassuring.”

In the end, Siggers could breathe easier. With a combination of modern technology and carefully applied human muscle, the Sphinx of the Pharaoh Ramses II—the largest sphinx in the Western Hemisphere—successfully completed its short but stressful journey from one side of the courtyard to the other. Fueled by four “air dollies” that shoot up compressed air, the 25,000-pound statue of a lion with a human head essentially floated an inch or two above the causeway, with some workers slowly pushing it along to navigate inclines and turns. Brian Houghton, the museum’s chief building engineer, described it to WHYY as a “glorified hoverboard, like from Back to the Future.”

Following the three-part, 300-foot move—which began two days earlier when the sphinx was lifted by hydraulic heavy machinery from its original base in the Lower Egyptian Gallery and placed on a custom-built track—it ended up in its new home as the centerpiece of what will be a renovated Main Entrance Hall, so that visitors can immediately see the museum’s most prized attraction upon entering. A central component of the museum’s Building Transformation Project [“Penn Museum Makeover,” Sep|Oct 2017], it will debut to the public there on November 16, along with new galleries and a “beautifully restored” Harrison Auditorium, Siggers says. “The journey of the sphinx represents a larger journey this museum is taking,” he adds, calling it a “red-letter day for this museum, and a red-letter day for the city, as well.”

Philadelphia has a unique relationship with the sphinx, first welcoming it to its shores in 1913, after it had been discovered in the ancient ruins of Memphis, Egypt, by English archaeologist Flinders Petrie and offered to the Penn Museum. As documented in the 2015 book The Sphinx That Traveled to Philadelphia [“Century of the Sphinx,” Nov|Dec 2015], it arrived from Egypt, via steamship and with much fanfare, to a Port Richmond pier, where it was lifted by a giant crane onto a railcar and transferred through Philly to the end of the rail line at 23rd and Arch Streets. It was then placed on a steel-reinforced wagon, pulled by a team of horses and 50 workmen.

Penn students organized a parade to welcome the sphinx to the museum’s garden, where it resided for several years until weather concerns caused it to be moved again, just inside the main entrance to a similar spot to where it will live now. The third move in 1926—and the last one until this year’s—placed it in the Lower Egyptian Gallery, where Siggers was convinced it would forever remain. So was Jennifer Wegner—associate curator of the Egyptian section of the museum and coauthor of The Sphinx That Traveled to Philadelphia—who notes this project “has made a little bit of a liar out of my husband [and coauthor Josef Wegner] and me. When we wrote the book about the sphinx, we said it would never, ever leave the gallery. It’s impossible, it’s impossible, it’s impossible. Guess what? It’s possible.”

Siggers admits to initially being “the grumpiest person in the room” when the idea of moving the sphinx in conjunction with the Building Transformation Project was floated, simply because the gallery had been built around it and he had “been told since I got here that it can’t be done.” But he allowed engineers to explore the possibility and was intrigued by some of the methods they came up with, which included lifting the sphinx by crane and breaking a hole in a wall, “which would have been more dramatic.”

Once museum officials, structural engineers, and other contractors set and put the final air-dolly plan into motion—and soil engineers tested the soil to make sure it was dry enough for the pylons to hold the sphinx’s 12.5-ton weight (which had been determined by 3D imaging)—the anticipation became palpable. “Do we cheer?” one onlooker in the courtyard asked a colleague, shortly before the sphinx’s blunted face poked through a second-story window (it was too big to fit through any door) a little after 10 a.m. on June 12. Yes, they cheered. One of the crew members tipped his hard hat in response. Schoolchildren pressed their faces against windows to watch. Other museum guests scampered for the best vantage points so they could witness a monumental move that took most of the day.

“The sphinx has long sparked fascination, especially among our younger visitors,” Siggers says, calling Ramses II, who reigned in Egypt from 1279 to 1213 BCE, “the big Kahuna of Pharaohs.” Carved in his honor out of a single piece of red granite roughly 3,000 years ago, Penn’s sphinx has “become the iconic object of the museum,” Siggers says. “And I’m really glad he’s going to be the first thing you see when you walk in the door.” —DZ