New York’s Success Academy charter school network has been lionized for its sky-high test scores and robust curricular offerings—and decried for a rigidly disciplined school environment one opponent described as “abuse.” Opinions are just as divided on its combative and committed leader, Eva Moskowitz C’86. She’ll be happy to tell you who’s right.

BY JULIA M. KLEIN | Photo by Don Hamerman

An unusual April snowstorm has blanketed Manhattan with slush. In the gray hour after dawn, my taxi slides uptown across wet, icy streets, disgorging me at the modest sidewalk entrance to Success Academy Harlem 1.

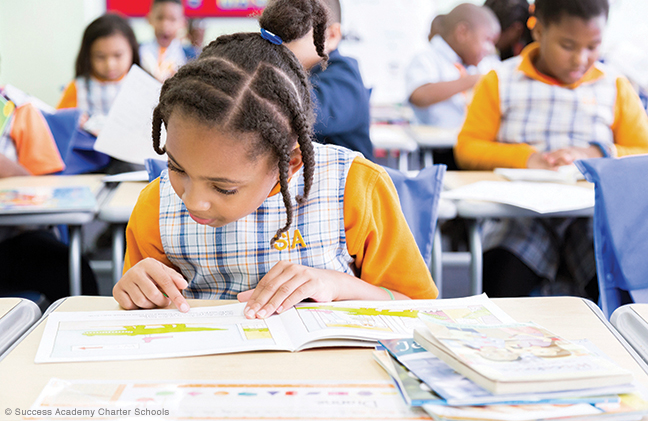

Uniformed in orange and blue, students here—“scholars” in the parlance of Success Academy Charter Schools—are arrayed on identical, multicolored rugs divided into rows of squares. A circle within each square indicates where these elementary school-age kids must sit, with hands still and eyes “tracking,” or following, whoever is speaking.

The rugs, says Success CEO and founder Eva S. Moskowitz C’86, are one element of the network’s school design, which prizes order, efficiency, and accountability—but not those qualities alone. According to Moskowitz, her 47 New York City schools, with their enriched curriculum and emphasis on college prep, embody “joyful rigor.” Ongoing teacher observation, a long school day,and engaged parents who are required toread to their elementary school-age children at home are other aspects of a complex, evolving formula that Moskowitz and her staff continue to tweak.

The 54-year-old CEO is a fierce, compact, indefatigable presence in a red dress ornamented by a dramatic crystal necklace and her trademark spike heels, which don’t seem to slow her down. “The most towering 5’ 2” person in the universe,” quips Derrell Bradford C’98, executive vice president of the education nonprofit 50CAN and a Success board member. Moskowitz is living her own creed of high expectations, creating an expanding network of charters that has made her a potent, controversial force in both political and educational circles [“Alumni Profiles,” May|Jun 2009].

Charter school advocates use the words “remarkable” and “incredible” to describe her accomplishments. Though she is an avowed liberal Democrat, she was interviewed by then-President-Elect Donald Trump W’68 for the post of US Secretary of Education. (Her assistant, she says, was frantic at not being able to reach her when he called—she was in a classroom coaching a second-grade math teacher.) After the interview, Moskowitz withdrew her name from consideration, and Trump ultimately tapped billionaire charter school champion Betsy DeVos for the post.

With her sharp tongue, combative nature, and unconcealed ambitions, the former New York City Council member remains “the most polarizing figure in New York City education today,” in the words of Diane Ravitch, an education historian at New York University and a prominent charter school critic. Carol Burris, executive director of the Network for Public Education, calls Moskowitz “extraordinarily talented,” as well as passionate, fearless, and abrasive. The one-time Long Island high school principal deplores Moskowitz’s denigration of the New York public school system and dislikes her pedagogy and disciplinary methods. Nevertheless, “I think she does have the heart of somebody who wants positive change,” Burris says.

On the day of my visit, Moskowitz is explaining what makes Success tick to a classroom of David Rockefeller Fellows—vice presidents, managing directors, law firm partners, and other rising titans of business who may one day number among the network’s donors, executives, or board members.

One question is just how Success, which relies on a mix of public funds and philanthropy, has earned such dazzling scores—the highest in the state—on standardized tests. Educating a population that is 76 percent low-income and 93 percent children of color, at a fraction of the per-pupil spending of many suburban districts, it has vaulted its scholars past such upscale enclaves as Jericho, Scarsdale, and Chappaqua, not to mention the city’s traditional public schools. “It’s not that we’re closing the achievement gap,” says Moskowitz, never one to mince words. “We’re reversing it.”

Another issue is just how useful a model Success, which as of the current school year is serving 17,000 students, offers for public education in general. On this, as on just about every aspect of the network, opinions diverge. But Moskowitz says that she has been approached to start schools elsewhere, domestically and abroad. Memphis called, and “Dubai wants us,” she says. “I don’t really want them.” For now at least, she is committed to New York City, where she plans to open 100 schools, with about 50,000 students, within the next decade or so.

Moskowitz leads the Fellows on a breakneck 25-minute tour of her pilot school, which opened in 2006 with 165 students chosen, as state law requires, by random lottery. By 2017, about 17,000 children were vying for 3,000 available slots, a tribute to the network’s results or, its critics insist, Moskowitz’s marketing savvy and fundraising prowess. Two 2010 documentary films, The Lottery and Waiting for “Superman, ” chronicled that often heartbreaking, high-stakes process. “Last year, we sent 14,000 kids home empty-handed,” Moskowitz tells the Fellows. “And those kids most likely will not learn to read.”

We march quickly through immaculate corridors, past walls covered with bright displays of student artwork. For five minutes each, we crowd into the back of classrooms equipped with white smartboards and bins of carefully chosen books. Students are quiet and attentive. A first-grade reading teacher leads a discussion about a picture book. A first-grade science teacher shows how an oscilloscope represents sound waves. Kindergarteners engage in block play, with one duo partnering to build a model of New York’s Flatiron building. Elsewhere, students deconstruct “number stories” in math, learn chess strategy, or pursue art projects. Direct instruction usually comprises only the first few minutes of each class period, after which students work in pairs or individually and then share their ideas with the group. Every segment is timed.

Even now, Moskowitz, a former college professor and, for three years, the principal of Harlem 1, stops on occasion to pull teachers aside and provide feedback, as her principals do regularly. Relentless in her focus, she tells the Fellows that a math class was paced much too slowly, and that the reading teacher could have asked better questions. Always, Moskowitz wants more, better, faster; her schools are a laboratory where the experiment is never quite finished.

“What you saw here,” she tells the Fellows after the tour, “is a replicable model. Everybody is executing against one school design. So the dot rug is in every classroom, the curriculum is the same, the assessments are the same, the teacher training is the same, the school calendar is the same, the books in the school library are the same. And some people view that, in the education reform wars, as a constraint on teachers and principals.

“And in my experience,” says Moskowitz, a battle-hardened veteran of those bruising wars, “it’s the opposite—it frees people up to be responsive to the children in front of them.” Teachers find both “creativity” and “autonomy,” she says, “in really knowing the kids in front of them as mathematicians, as readers, as scientists.”

There is little guesswork involved. “We are a very data-driven place, from the home office down to the teacher level,” Moskowitz says. “We expect teachers to know the reading level and the reading goals and struggles of every kid in her class. [A phonics teacher] would know which letter sounds every kid does not have yet. That is the level of granularity. Really the trick is to have the organizational infrastructure to know what to do about that. How you use data to change practice—that really is the key.”

The product of New York public schools, including academically selective Stuyvesant High School, Moskowitz once imagined reforming them—and then running for mayor, an ambition she has put on hold. “It’s no secret that I have an interest in political office,” she says.

Stymied after losing a 2005 race for Manhattan borough president, she embraced the offer by two hedge fund managers, Joel M. Greenblatt W’79 WG’80 and John Petry W’93, to open a charter school in Harlem. “We were looking to build a replicable model, and share it as widely as possible,” Greenblatt recalls. They settled on Moskowitz as their CEO because “she was so passionate, smart, thoughtful, and driven.” The issue of replicability beyond Success itselfremains unsettled. “I think Eva’s rare, to be honest, and special,” Greenblatt says. “It would be tough to replicate Eva. But there are other talented people out there.”

Today Success Academy Charter Schools, under the aegis of the State University of New York’s Charter School Institute, offer a free public education to thousands of children who could never afford a private one—in a system unbound by many of the regulations, including union work and tenure rules, that Moskowitz believes hobble traditional public schools.

A micromanager with almost inexhaustible energy, Moskowitz works about 80 hours a week andcalls herself “a notoriously demanding boss.” In her recent memoir, The Education of Eva Moskowitz (Harper, 2017), she writes that her board “feared I was running people into the ground” as Success grew and suggested she bring in a more experienced CEO. Instead, during the period 2012-13, she sought out management advice, streamlined Success’s organizational structure, and resolved to be less critical of herself and others.

She continues to be involved in virtually all aspects of the network’s operations. At her first school, she dealt with the issue of bathroom uncleanliness by instituting a “golden plunger” award. Leaving Harlem 1 after the Rockefeller Fellows event, she still stops to listen to a custodian’s complaint about sinks that are too small. Unsatisfied with reading curricula on the market, she developed her own THINK Literacy curriculum, which emphasizes independent reading. She’s now working on fine-tuning the writing curriculum, as well as developing more sophisticated high school math and science offerings. (Success’s Ed Institute makes its curricula and other aspects of the network’s model available for free online.)

Success students prepare intensively for state tests, participating in “Slam the Exam” rallies, earning incentives (such as “effort parties”) for improvement and extra help whenthey are struggling. Moskowitz also insists that elementary schools provide five days a week of laboratory-oriented science, as well as sports, chess, and arts education. Love it or hate it, Success embodies Moskowitz’s own values. She sends two of her three children, admitted by lottery, to Success schools. “I wake up every day,” she says, “and I’m thinking about the hundreds of thousands of children who don’t get to go to a loving, intellectually stimulating school that offers art, music, and dance—and that pains me.”

Not everyone is a fan. Critics argue, first of all, that charters such as Success divert valuable resources from district-runschools, while declining to educate the neediest children. They argue that those superior test results are (at least in part) an artifact of the network’s alleged culling of poor-performing students – and that the price for achieving those stellar scores is too high. “[I]t is possible to winnow out the most intractable students and be left with the best and most compliant ones by selective attrition,” Ravitch writes.

A January 2016 federal civil-rights complaint, filed with the Department of Education on behalf of 13 children from 10 Success schools, charged that the network discriminates against students with disabilities by failing to provide“reasonable accommodations” for them and retaliates against them with measures such as repeated suspensions and early dismissals “to coerce them to leave.” The complaint, as well as a similar lawsuit involving five plaintiffs, followed the revelation of a “Got to Go” list of 16 students, many with behavioral issues, created in December 2014 by the novice principal of Success Academy Fort Greene. The list was reported in October 2015by The New York Times. By then, the principal already had been reprimanded, Moskowitz says. She called the list a mistake, not reflective of Success policies. Ann Powell, Success’s executive vice president of public affairs, says that the complaint and the lawsuit are still pending, and that Success has filed a motion to dismiss the suit.

The Success website says that 15 percent of the network’s population consists of former or present special needs students. “Our special education kids do twice as well on state math testsas the general edkids at public school, and they also outperform on English tests,” Greenblatt says. But Moskowitz also says that her schools aren’t the right fit for everyone.

That includes teachers. Turnover is higher than in district schools, with the average teacher lasting just three years. Job sites such as Glassdoor cite the high stress and long hours, but also praise the generous pay, benefits, and training opportunities. As part of what Success calls a “culture of continuous improvement,” principals and teachers regularly review a variety of data—from tests to unexcused absences—across schools, grades, and classes to monitor progress. Some teachers are designated as exemplars and receive extra compensation to serve as models for others.

For teachers who perform well, mobility can be rapid. Michele Caracappa C’02 was a founding teacher at Harlem 1. Twelve years later, she is the network’s chief academic officer. “We’re never satisfied—that’s a big Success trait,” she says. “We don’t take the time to make five-year plans here. There’s big ambition in terms of what we want to accomplish in any given year, a really hearty ambition and vision that comes from [Moskowitz] that filters into everything we do.”

Paloma Saez C’12, who has taught at Success elementary schools in Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Williamsburg, says she chose the network because of “deeply craving someone to just help adjust what I was doing, to help me become a better teacher.” During her first two years on the job, Moskowitz was frequently in her classroom to coach her. “The first time it’s definitely nerve-wracking,” Saez says. But she realized “it’s not about evaluating you as a teacher—it’s about partnering with you for the kids.”

Student attrition is another issue, though Greenblatt claims it is lower than at district schools. The recent high school graduating class of 16, the first in the history of Success, started as a cohort of 73 first-graders. Critics seize on the fact that Moskowitz won’t admit students—or “backfill” the vacancies, in education-speak—after fourth grade because she believes that older students would be too far behind academically. Neil Campbell, director of innovation for K-12 education policy at the Center for American Progress, says this policy may become less defensible as Success continues to expand.

Another flashpoint has been “co-location.” In her memoir, Moskowitz describes in gritty, righteous detail the constant political skirmishes she has fought to allow charter schools to share space, gratis, in underutilized public school buildings. Most of her schools are co-located with district schools—a practice that Campbell says New York, with its expensive real estate and sympathetic political officials, is unusual in permitting. Closing her schools for the day, Moskowitz has led rallies of Success parents, teachers, and students to Albany to pressure legislators on this and other issues, harnessing her constituency as a political force. New York’s Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo has been supportive of Success and other charter schools, as was former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a Republican in his first two terms and an independent in his third.

During his 2013 mayoral campaign, the labor-backed Democrat Bill de Blasio took a more antagonistic tack.“Time for Eva Moskowitz to stop having the run of the place,” he told a United Federation of Teachers crowd. “She has to stop being tolerated, enabled, supported.” City Education Department spokesman Doug Cohen played down the enmity this summer, saying the city supported “building collaboration between district and charter schools in order to share best practices and support the needs of all students.” Meanwhile, the battles over co-location continue.

“There’s a lot of resentment around her use of the political system to gain advantage for her charter school chain,” Burris says. She and others also are critical of Moskowitz’s compensation, now $750,000—more than double the $345,000 salary of New York City Schools Chancellor Richard A. Carranza, who oversees 1.1 million students in more than 1,800 schools. Success’s Powell says taxpayer money accounts for $195,000 of Moskowitz’s salary, with the balance privately funded.

In 2016, SUNY, which charters Success, investigated the network’s strict disciplinary policies—more fallout from the “Got to Go” list—but found no wrongdoing. Leonie Haimson, executive director of the nonprofit Class Size Matters, nevertheless uses the charged word “abuse” to characterize the school environment. “She’s run this charter chain something like a military exercise,” Haimson says. “She’s bullied people, including our mayor [de Blasio], to give in to her will over and over again.”

Mike Petrilli, president of the pro-charter Thomas B. Fordham Institute, says there is no question that “it’s Eva’s way, or the highway.” Success is “not for everyone,” he says. “People have to buy into the whole model. They can’t pick and choose.” If you don’t like the model, he adds, “Fine—don’t teach there, don’t send your kids there.”

On the other hand, he says, “the results are incredible.” In 2017, according to the Success website, 95 percent of its scholars tested proficient in math, while 84 percent were proficient in English Language Arts. The comparable percentages for New York City district schools were 38 percent and 41 percent.

Given that achievement typically correlates with socioeconomic status, the 2016–17comparison with a wealthy district such as Scarsdale may be even more startling. With a median household income of $291,542 (compared to $32,191 for the census tracts served by Success) and per-pupil spending of $29,251 (compared to $14,027 for Success), Scarsdale delivered poorer test results than Moskowitz’s schools: 82 percent proficiency in math, and 74 percent in English.

“I totally understand why some people don’t like Eva, especially when she gets engaged with politics and advocacy,” Petrilli says. “But when it comes to Eva as an educator, I just find it hard to understand why anyone wouldn’t celebrate her as somebody who has broken ground.”

Frederick M. Hess, resid ent scholar and director of Education Policy Studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, says that he’d “ be the last person to say she’s cracked the code,” noting that public schools could never require a comparable level of parental involvement. Not only must Success parents supervise homework and keep reading logs, but they are expected to respond to all school communications within 24 hours. “If Success was saying, ‘Every school should be run like ours,’ that would be a huge problem—because it is a stressful model. It’s not a good fit for everybody,” Hess says, “so you do get more attrition than in some other models.

“I don’t think the big problem with American education is, on the whole, that it is too demanding and too rigorous,” he adds. “If you are looking for schools that are more accommodating, less demanding, it’s not that hard to find them.”

Not even her harshest critics question Moskowitz’s single-mindedness or her passion.

The daughter of academics, the educator prides herself on having grown up in Harlem, and on living there still with her lawyer husband (and high school sweetheart), Eric Grannis, and their three children. (In one scene in The Lottery, a New York City councilwoman questions whether Moskowitz actually resides in Harlem and demands her street address; the councilman representing Harlem vouches for her.) Moskowitz’s father, a mathematician, taught at Columbia University; her mother, an art historian, recently retired from the State University of New York at Stonybrook. “I thought everyone got a PhD!” Moskowitz recalls. “I was living in a narrow world.”

At age 10, with her father on sabbatical in Paris, she attended a “not terribly inspiring” French school, where “underlining was the main thing you were supposed to do” and “the teachers were always on strike.

“Dictation was particularly challenging because I didn’t know the language,” she continues. “Everything was scored out of 20, and I remember getting to a six at one point, which was very poor. But what I learned was that, when I came back, I hadn’t missed anything.” Even Stuyvesant, its fine academic reputation notwithstanding, was at best a mixed bag, she reports in her memoir. “Many [teachers] … were disengaged or ill-prepared,” she writes, and the AP physics teacher sometimes showed up drunk.

Moskowitz was entrepreneurial from a young age. One of her early efforts, a cheesecake cart, went awry. But the story does suggest something about her intensity. “I made an incredible number of cheesecakes—every kind,” she says. “I had this huge book on making cheesecakes, and I thought I was going to sell them, and then I ran out of time, because I went off to Penn. But I spent four weeks, every evening after work, making cheesecakes, driving my parents crazy.” In the end, she says, “my parents actually started insisting that I stop because they were gaining weight.”

The next setback was more painful. After both she and Grannis started college (he attended Columbia), he ended their relationship, citing Judy Blume’s young adult novel, Forever, “about how high school relationships don’t last forever.” The citation seems to have bothered her almost as much as the breakup itself. “I was sort of insulted,” she says. “First, I didn’t know boys read Judy Blume. And he was very sophisticated,” a comparative literature major. “This was a man who introduced me to Flannery O’Connor!” Would she rather that he had quoted Shakespeare? “Yes,” she says. “That would at least have had more credibility.” In their case, it was the breakup that didn’t last.

At Penn, after being told her writing was weak, Moskowitz turned to the writing center for help, and the lessons she absorbed stayed with her. A history major, she remembers such “stellar” professors as Drew Gilpin Faust G’71 Gr’75 Hon’18, a historian of the American South who recently retired as the first female president of Harvard University; Bruce Kuklick C’63 G’65 Gr’68, Nichols Professor of American History Emeritus; and the late Michael B. Katz, a scholar of poverty who helped found the University’s urban studies program.

“I was so inspired by the quality of the faculty. I took advantage of all the office hours. I went religiously,” she says. Her honors thesis focused on student activism in the 1930s. Outside the classroom, she founded the Political Participation Project, an organization “oriented toward getting students involved in political activity, including voter registration.”

It was a harbinger of a career to come. But, first, Moskowitz turned to the family business—academe. She earned her doctorate in American history at Johns Hopkins, and eventually landed a one-year post as an assistant professor at Vanderbilt University. Her doctoral dissertation became her first book, In Therapy We Trust: American’s Obsession with Self-Fulfillment (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

“People ask me, ‘Are you against psychological happiness?’ Of course not! It just goes back to civic engagement,” she says. “There’s some tension between being focused on the self and focused on the public good. And in no other country is there as much attention to [the question of] ‘Is one happy? Is one’s ego being taken care of?’”

Bouncing around the academic job market, Moskowitz realized, “I didn’t want to be a professional historian for the rest of my life.” She was competent, she says, but exploring big historical questions was not her greatest strength. “If you’re Einstein, then you should pursue a theory of relativity,” she says. “But I had no illusions about that.”

More pressing was her desire to effect social change. “That was something I grew up with,” she says, with her mother working as a draft counselor during the Vietnam War, and both parents involved in the antiwar movement. “Dinner table conversations were about how to make the world fairer, more equitable.”

Years earlier, Grannis had advised her to enter politics. In 1996, despite making about 15,000 cold calls, Moskowitz narrowly lost her first race for New York’s City Council, a crushing defeat. She took a job at Prep for Prep, a nonprofit that worked with gifted minority children. In 1999, undeterred by having a one-year-old son, she ran again—and won. “It was really public education that motivated me,” she says. “It just seemed incredible that the school system was failing so many children.”

She likens her work as chair of the council’s education committee to historical research. In 2003, she made her name, and plenty of enemies, with contentious hearings on the city’s union contracts with teachers, principals, and custodians. Before the hearings, she says, she sent each participant some homework: a 25-page list of questions to answer.

“Just to be clear,” she says, “I could have said, ‘I’m going to ignore the elephant in the room. I want to have a successful political career.’ As a Democrat, you do not touch the third rail of Democratic politics: unions and the contract.” (Success, like most charters, has no unions. “Labor and management, first of all, are not on separate teams,” she says. “I don’t know how to run a school that way. I’m there to support [teachers] in developing their practice.”)

Moskowitz says that she entertained “the perhaps naïve notion … that you could be honest about the challenges of public education, including the role of the contract—and survive politically.” But her failed race for Manhattan borough president, with her 16-hour campaign days no match for the anti-Eva efforts of the powerful teachers union, “proved the opposite—which still saddens me to this day.”

After the loss, her husband had yet another job idea: Why didn’t she start a charter school? She had been offered a “figurehead” post leading a teacher-training program for the city Department of Education, and she’d considered educational philanthropy. “But giving out money or support,” she says, “didn’t seem like my cup of tea. I was really impatient to solve this problem. It has so much emotional urgency for me.”

Meanwhile, Grannis had been providing legal advice to Petry and Greenblatt, and they asked Moskowitz for help with their charter application. “The next thing I knew, John and Joel offered me this job,” she says. “I was frankly a little taken aback. I didn’t know how to run a school.” When she started to explain her vision, she encountered little pushback: “They just wanted a good school. What was important to Joel—which is also important to me—is that it be financially disciplined.” The point was to produce better results than district schools on essentially the same dime—or less. (For 2018-19, according to the New York City Independent Budget Office, spending in district schools will rise to $24,109 per pupil, compared to $15, 807 in funding for Success students. That doesn’t count the benefits of co-location, nor philanthropic support for charter school start-ups.)

In her memoir, Moskowitz is acidly critical of her press coverage. One pet peeve is the notion that a smaller special-needs population or high attrition is responsiblefor the sky-high test scores. “The mathematics just doesn’t work,” she points out.

Then there’s the frequent categorization of Success as a “No Excuses” school, a rubric applied to charters such as KIPP, Achievement First, and others with high behavioral and academic expectations. “I don’t think that’s accurate,” she says. “If you’re a ‘No Excuses’ school, then there’s no joy and there’s no love, there’s no second chances. Whereas in our world, if you’re in kindergarten, every five minutes is a new day—you don’t hold grudges, you get a new chance. The schools are to make mistakes—that’s the whole point of them: You learn from your mistakes.”

Moskowitz says that, far from pushing them out, Success mobilizes around children and families in crisis. In one instance, a child was hospitalized and endured multiple surgeries as a result of abuse. “The entire staff,” she says, “showed up at the hospital, and the kid asked when he woke up from surgery, ‘Is it my birthday?’ Because he couldn’t believe there were balloons, and everyone was there.”

She also professes bafflement at negative portrayals of Success’s insistence on common courtesy. “For hundreds and hundreds of years, schools taught things other than reading, writing, and arithmetic, including ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ or respecting your peers and respecting adults and so forth,” she says. “And now if you do it, you’re some weird fuddy-duddy.”

It’s important, she says, to see these criticisms and others “through [the lens of] aggrieved politics and not take everything literally.” While the political debate about charters continues, she says, “I think it’s over empirically. That doesn’t mean that every charter is delivering on its promise, or every district school is not delivering on its promise.

“And by the way,” she says, “for parents, none of this matters. Parents don’t care if it’s a charter or if it’s a district—they want a good school for their kids. I think that is going to ultimately flip the politicians.

“To me, it’s not even a charter-district debate. It’s really, ‘How do we live in the greatest city on earth and have 90 percent of our schools not working for the most vulnerable students in our system? How do we accept that as normal?’ That’s not normal. So people are going to have to speak out.”

It’s indisputable that many charters nationwide, launched with such promise, have failed to produce results or, worse yet, been mired in chaos or corruption. “It’s like saying ‘Let’s not have any restaurants because some of them are bad,’” Moskowitz responds. “I am not saying that a charter guarantees that you will deliver a good education. I am saying that, everything being equal, a charter gives the freedom to deliver excellence. But it still takes enormous executional competence to deliver excellence. It’s hard! And the poorer the kids you serve, the harder it is.”

Given the rigors of Success, Fordham’s Petrilli says, “It takes a certain kind of family willing to commit to it. It wouldn’t work as a traditional public school. But there are a whole lot of families out there who are craving something like this. For low-income, for working-class families, this is a godsend. If they are willing to do the work, then [Moskowitz] is willing to give their kids a real shot at succeeding in the American meritocracy.”

The charter network’s emotional high school commencement, held June 7, offered a glimpse of how that success might look and feel. All 16 members of the Class of 2022 (so named for their aspirational college graduation year) have been accepted into four-year colleges or universities, including Barnard College, Emory University, Tufts University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

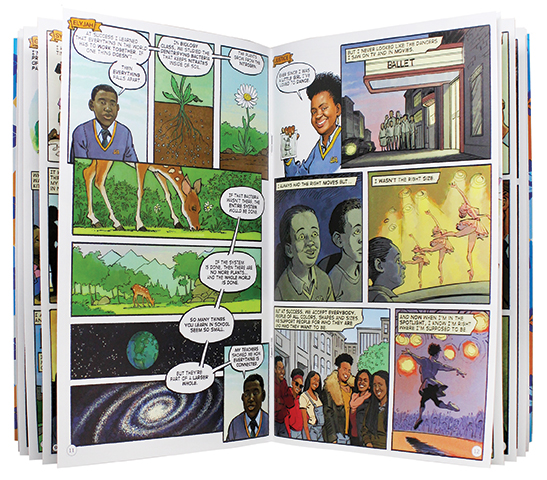

To celebrate this milestone, Moskowitz has rented out Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center and festooned it with orange and white balloons. A graphic novelette, Success Stories, based on their college essays, highlights each graduate’s story: Sydney Cairo McLeod’s battle with sickle cell anemia; Noumoutche Elijie Fanny’s effort to overcome racial stereotyping; Lexi Torres’s internship with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor. “I’m only in high school,” Torres writes, “and look where I am.”

Security is tight, but the crowd’s mood is giddy, electric. Board members, families, teachers, administrators, and students stream through the doors. Anticipating their own future, juniors from the High School of the Liberal Arts in Manhattan are perhaps the giddiest of all. They punctuate the occasion with cries of “We love you, Mr. Malone!” in tribute to their principal.

“Parents and families, you entrusted us with your children 12 years ago,” Moskowitz tells the assemblage, fighting back tears. “We had no school building, we had no principals, we had not very good teachers, and I frankly did not know what I was doing. But I had a vision for an excellent school that could be achieved where every single kid not only learned to read, but loved reading … Since then, we’ve faced down many challenges together to reach today.”

Class speaker Kelvin Joshua Jennings, headed for Tulane University, reminds his fellow graduates that they persevered and beat the odds. “All of us are going to college. We are going to college,” he repeats. “I think we’re ready.”

Principal Andrew Malone, his voice breaking, underlines the afternoon’s mixed emotions. “I know that as excited as you are for college, there is a part of you that understands and feels this moment as a loss,” he says. “And a part of you that is sad and maybe even a little bit scared to be leaving one another. I know that is exactly how I feel watching you go.

“It’s okay,” he says. “Because you will always have one another, because you are, in large part, one another.” He enumerates, one by one, the unique qualities of each graduate, so precisely that even a stranger feels that she knows them: Mame Diarra Seck, the gifted writer; Justice Gloria Jane Mabry, the life of the party; Lexi, the warrior for social justice; Moctar N. Fall, epitomizing both head and heart. “Whatever you need, you have,” Malone says. “What you have seen every day in one another, you will have forever in yourself.”

At the reception afterward, the main order of the day is not the generous buffet, but family photography memorializing the occasion. In the ladies’ room, I see a middle-aged black woman at the mirror, dabbing away her tears. I guess, correctly, that she is the mother of a graduate.

“The community didn’t have what we needed for our children education-wise,” says Keisha Rush, a health-insurance agent living in Harlem, whose son, Elyjah Mark Anthony Pellew, is planning to attend the University of Southern California to study environmental science. “So we took a chance with Eva. And it worked out for the best.

Oh, Eva’s excellent, to open the door for these kids the way she did—I applaud her,” Rush says. “When we started out, she said it was a marriage. And it surely was.”

Julia M. Klein has written for The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Mother Jones, The Nation, Slate, and other publications. Her Gazette profile on Eli Rosenbaum received a first-place award this spring from the American Society of Journalists and Authors. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.

To the Editor:

Success Academy is the best argument for parental choice (“The Rigors of Success”). For some children, Success Academy is a disaster; for others, it is a godsend. Only parents should be able to make that determination. Focusing on Eva Moscowitz is a distraction.

Sincerely,

Walt Gardner, C ’57

376 Bonhill Road

Los Angeles CA 90049

310-472-1964

Walt Gardner blogs about education at theedhed.com.

Thanks for well written, balanced, and research article on Dr. Moscowitz overcoming mandates (testing, etc.) and barriers to education, especially giving productive feedback and training to allow teachers to improve their “practice” as professionals.

Sincerely,

Toby Decker