Second in a 110 part series.

In his Opening Day address Provost Harrison called attention to the fact that every room in the University’s fledgling Quadrangle dormitories was not only taken, “but with a ‘waiting list,’” adding that the construction of more dormitories “has become an immediate and pressing need; and it is one to which all of us should call public attention.” He was certainly doing his part. A report on the opening of Robert Morris House included the news that it had been funded by the great-granddaughter of the ‘Financier of the Revolution’ honored in its name—who also happened to be Harrison’s wife.

The news that the Houston Club would be getting its own “sub-postoffice” (which I’m pretty sure was still there in the Seventies) shared space with a notice that famed Irish poet William Butler Yeats would lecture “in the auditorium of the Houston Club … on ‘The Intellectual Revival in Ireland.’” (No word on whether Penn’s two future Modernist giants, Ezra Pound C1905 G1906 and William Carlos Williams M1906 Hon’52, who were both on campus at the time, attended.)

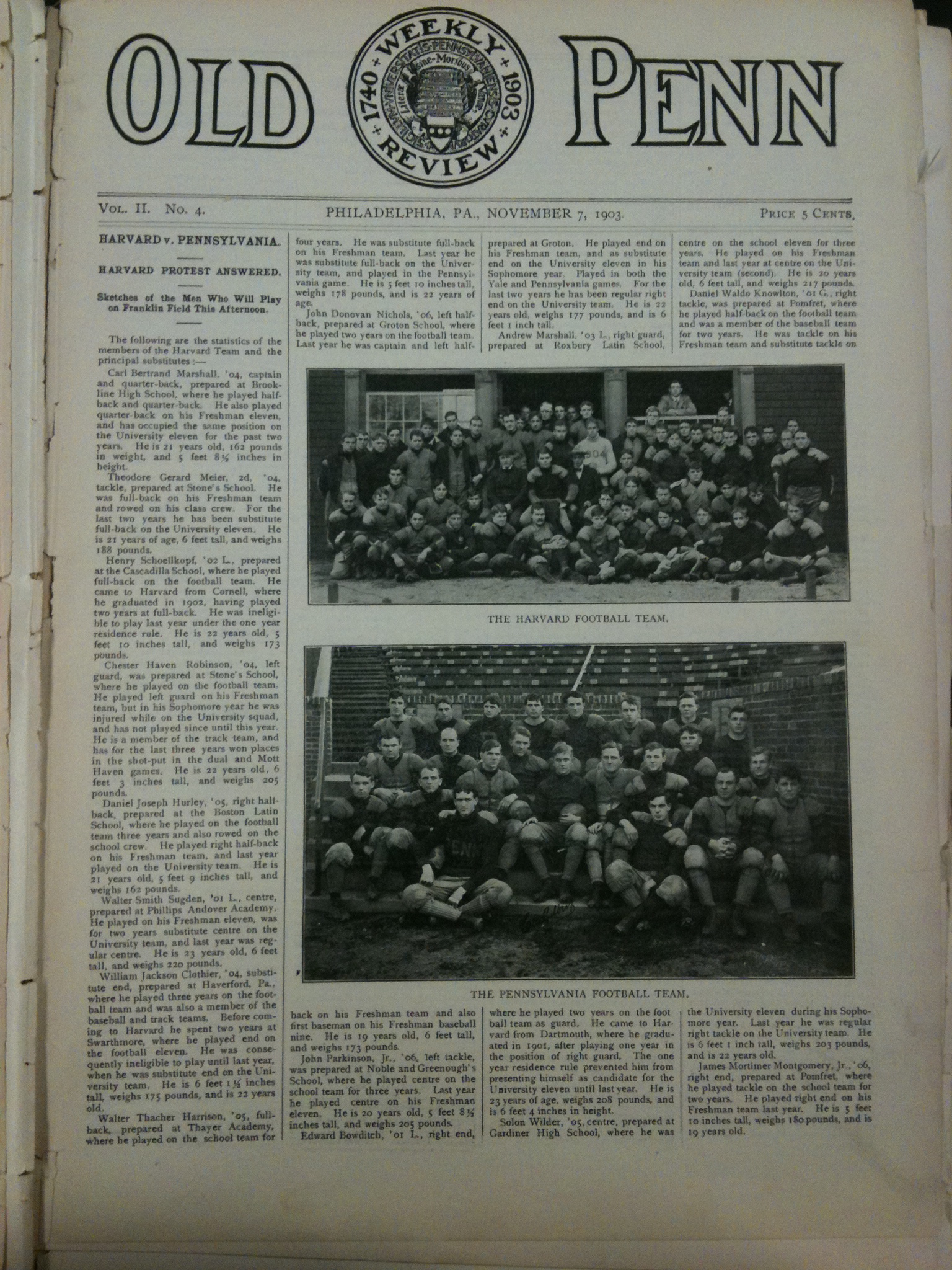

It was a mostly disappointing football season: “[F]or the sixth consecutive time the Red and Blue bowed to the Crimson, and the result was never the least in doubt, it being apparent from the start that while Pennsylvania was good, Harvard was heavier, faster, and played better football.” From the pictures on the front page, it looks like they also had at least twice as many players. The season ended on a higher note, however, with a 42-0 thumping of Cornell; “A Great Game of Football on Franklin Field, followed by the Snake Dance.”

The debate team continued to receive ample coverage. This year’s team included a very young Scott Nearing C1906 Gr1909, whose controversial firing from Penn’s faculty, a bit more than a decade later, would help create the modern tenure system. And Cornell would get its own back when Penn’s debate team fell to the Big Red “on a technicality” later that year.

An editorial weighing “College Debating Versus Athletics” had it both ways, asserting: “These two sports, the mental and the physical, should not appeal to different types of college men, but should engage the time and enlist the praise of all.”

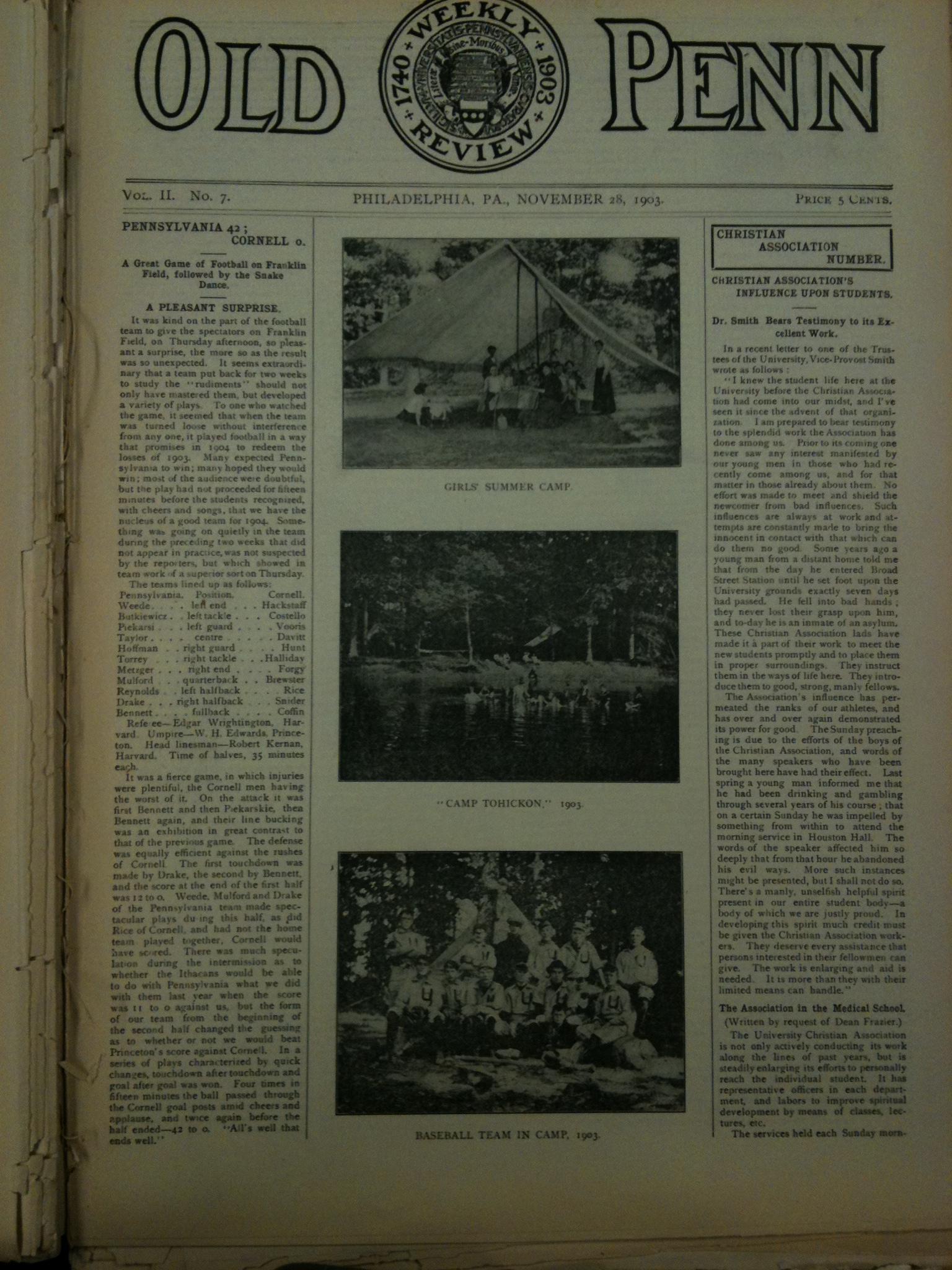

But it wasn’t all snake dances and opposing arguments. The November 28, 1903 issue gave over most of its pages to a discussion of the charitable work being done by the Christian Association, both in morally influencing the student body and providing practical assistance to the city’s underprivileged through camps and settlement houses. Vice Provost Edgar Fahs Smith recalled the dark days before the CA, telling the tale of a “young man from a distant home” freshly arrived in the city: “He fell into bad hands; they never lost their grasp upon him, and today he is an inmate in an asylum.”

A story on “the University’s rapid growth” noted that the campus encompassed almost 60 acres and more than 50 buildings—with more space needed, of course, for additional buildings and improvements. New medical laboratories were dedicated that spring, “located along Hamilton Walk, parallel with the ‘Old Field,’” giving the University “the most complete and extensive plant for teaching medicine in the world.”

This year a column headed “Houston Club Notes” was a regular feature, offering results of various contests (bowling, swimming, billiards, etc.) and news of upcoming events: “The smoker on Tuesday evening, February 16 will present an attractive program of exercises, consisting of fencing contests and gymnastic exhibitions, accompanied by music.” As it turned out, this event, a subsequent column reported, was “attended by a reduced but enthusiastic audience,” which it attributed to the fact that “last Tuesday evening was so bitterly cold that students who had sought their rooms after supper probably remained indoors.”

In “A Summer Vacation,” a rare-for-the-time student essay, Julius Bernstein described the experience of traveling to Europe and back on a cattle boat as an inexpensive route to a tour of the Continent. On the up side, the work is not very demanding on the way over, and there’s none on the way back, when the returning ships are empty. On the other hand:

“The ‘bull-pusher’s” food and surroundings are not as easily accepted as the work. Breakfast is served at 8 o’clock, and consists of a stew of ‘salt horse’ and ‘spuds’ (potatoes), known as ‘scouse,’ one loaf of ‘punk’ (bread) and black coffee. The ‘scouse’ is varied twice a week by baked hash, ‘burgoo,’ or curry and rice. Dinner at noon consists of vegetable, pea, or bean soup, ‘spuds’ and ‘salt horse.’ Supper at 5 P.M. consists of black tea (so-called) and ‘hardtack.’”

The death of Albert M. Wilson, an African American who was known by generations of students and faculty as “Pomp” during his 50 years of working for the University, received extensive and sympathetic—if also patronizing—coverage:

“On Tuesday at noon the body lay in state in the chapel of College Hall, surrounded by many simple floral pieces—tokens of affection of his many friends. For over an hour a file of students, graduates, and members of the teaching force filed by the coffin to take a last look at the familiar face of ‘Pomp.’ The bell in the steeple tolled fifty strokes—one for each year of service, and the flag was at half mast.”

Afterward a procession including the University secretary, Jesse Y. Burk, “the Provost, Vice Provost, the deans, the faculty, students, graduates and friends, proceeded to the chapel, where the funeral service was held.”

Wilson, who began working as a janitor’s helper at age 13 in 1854, was the last living link to the University’s previous campus at Ninth and Chestnut streets. He eventually came to be a valued assistant to Dr. John Frazer C1830, Professor of Natural Philosophy and Chemistry. (Though nothing in Old Penn alludes to it, Wilson had a whole other life as a medical practitioner in the African American community around South Street, as noted in this biographical sketch on the University Archives website.)

Wilson’s skills and character were recalled in a mostly pretty awful but also kind of touching poem—“Pomp and Circumstance,” inevitably—that Frazer’s son, Dr. Persifor Frazer C1862, offered at his 1904 annual class dinner, reprinted in Old Penn:

How skillful, and patient, and wise, and persistent

He was as the Chemistry-Physics Assistant

…

Was it “Moon,” or the “Pendulum,” “Light,” “Electricity,”

He prepared every lecture with equal felicity.

He never forgot, and he seldom was worried.

He never neglected, and seldom was hurried

…

Pomp used circumstances; they did not use Pomp.

He has gone; yet however restricted his sphere,

Society gained by his tarrying here,

And some of the best will his passing deplore—

Can any of us for himself hope for more?