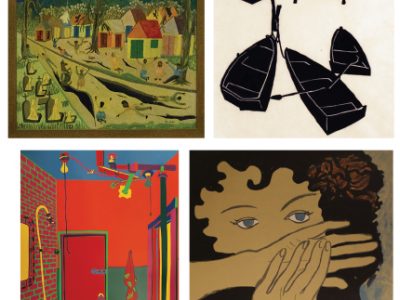

“Arcadia” by Sam Hyde Harris (1889-1977).

Eleven years ago, the Irvine Museum put together an exhibition that would be shown in Paris, Krakow, and Madrid. While the Irvine has put together no fewer than 65 traveling exhibitions during its 20-year existence in the California city whose name it shares, this one was particularly significant—it would be the first time the museum’s works of California Impressionism had traveled to Europe.

James Irvine Swinden W’76, the Irvine’s president, admits to being a tad apprehensive about the reception the paintings would get in the birthplace of Impressionism. (In fact, they had to remove the word Impressionism from the title of the accompanying book—which turned out to be a blessing, since the title they settled on, Masters of Light, was both more appealing and less derivative.)

When Swinden and his staff arrived in Paris, the head curator of the museum in question, the Mona Bismarck Foundation, “was bubbling over with enthusiasm, saying how wonderful the show looks and how successful it’s going to be,” Swinden recalls. “I asked her how she could be so confident about this, and she said, ‘Well, the two men we’ve hired to unpack your paintings and hang them for us are two of the best installers in all Paris.’ I said, ‘That’s very nice, but it doesn’t quite answer the question.’ And she said, ‘No, it’s perfect, because they just finished installing a Matisse and a Picasso show at the [Musée] d’Orsay—and they like your stuff better.’”

Masters of Light went on to break attendance records at all three venues. (In Krakow, the 30,000 visitors nearly quadrupled the previous record of 8,000.)

Seeing people enjoy that art so much was “really special,” says Swinden. It also validated the mission of the museum, which is dedicated to the “preservation and display of California art of the Impressionist period” (roughly 1890-1930) and committed to spreading the gospel of that “important regional variant” of Impressionism.

This past summer and fall, Penn’s Arthur Ross Gallery hosted another Irvine exhibition—California Impressionism: Masters of Light from the Irvine Museum—and for 10 weeks its walls emanated light from three-dozen plein air landscapes by the likes of Granville Redmond, Guy Rose, and Franz Bischoff. During an October reception, Swinden addressed several dozen members and friends of the Ross Gallery. He talked about the artists (the Philadelphia-born Redmond was a deaf-mute whose patrons included Charlie Chaplin) and some of the individual paintings (Redmond’s luminous “Nocturne,” for example, fused Impressionism with Tonalism). But mostly he talked about the museum and its unique collection, mission, and operating style.

Swinden has spent much of his life in and around Irvine, and the history of his family and the southern California landscape it dominated are part of the museum’s history as well. Amazingly, it wasn’t until the early 1990s that his mother, Joan Irvine Smith, began buying the roughly 4,000 paintings that make up its collection. She had previously collected English sporting art as well as art from China and Japan, and once she started buying works by California Impressionists she didn’t waste time. In January 1993 Smith, Swinden, and Athalie Richardson Irvine Clarke (Swinden’s maternal grandmother) founded the Irvine Museum.

“The museum was formed on two principles,” says Swinden. “One was that we felt that these paintings were by first-rate artists. But my mother also wanted to use the paintings to show what California looked like in its unspoiled condition—and do it in a non-threatening way. When people walk in and see these paintings, many of them say, ‘Wow, I live there and it doesn’t look like that anymore.’ So it’s an easy way to get people engaged in not only the beauty, but also maybe thinking about what they need to do to help preserve what’s left.

“In many ways,” he adds, “I’m finding that I had the same passion that my mother did about the land.”

Of course, Swinden is also a Wharton alumnus with a law degree from Loyola Law School, so he approaches his work from a slightly different angle than most museum executives. Early on, his role as president was more or less limited to the business and legal side, but he soon became involved in selecting paintings for exhibitions as well as in educational outreach and publications.

“Within five or six years I was pretty much, in a sense, running the museum,” he says, “even though we have an executive director [Jean Stern] who knows more about the art than I do.”

At first blush, it may seem surprising that the Irvine doesn’t own the office building in which it is located. But it makes sound financial sense.

“We did everything totally backwards from other museums,” says Swinden. “After 20 years, I’m more convinced that small regional museums might want to look at our model before they go and build a building.”

The Irvine is now on the ground floor of that office building, though it started out on the 12th floor. That first location was at times “bizarre” for a museum that had to accommodate busloads of schoolchildren (not to mention seniors who had to walk down 12 flights of stairs when the elevators malfunctioned). But the views from the 12th floor were “spectacular,” he says convincingly. “At that point many places were still pristine. You’d be looking at a painting, and then outside the window you’d see the scene. And you’re almost awestruck by that.”

At some point, Swinden acknowledges, the museum “would like to have a permanent location”—adding that a location in the Orange County Great Park, part of the Irvine Ranch (no longer owned by his family) is being considered.

In the meantime, “we really focus on making our collection available to the greatest number of people possible,” Swinden says. “One of my pet peeves with other museums is that they have wonderful collections, but 80 or 90 percent of the collections stay down in the vaults, and they trot ’em out every 20 years. I like to say, ‘Why can’t the big guys give a third-level curator a chance and put together an affordable show and have the public see these works of art by loaning them to other museums?’”

As a result, they formulated a policy in which they don’t charge a fee for an exhibition—“just shipping and insurance one-way,” he says. “Small regional museums can take our shows for about $10,000 to $12,000, and they only have to go to two patrons to get that, and it doesn’t break their budget.”

The fact that the Irvine just celebrated its 20th anniversary is both surprising and gratifying, says Swinden. “We were reflecting back on what we had done and accomplished—particularly the outreach we’d provided for our own community and throughout the state and country. It’s really been gratifying in many ways, because when we first started the museum, most people didn’t expect it to last.”—S.H.