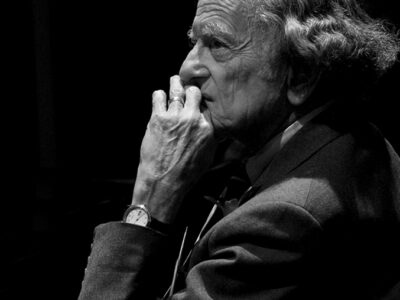

Poetry can be a means of rescue. Edward Hirsch Gr’79—poet, president of the Guggenheim Foundation, and chancellor of the Academy of American Poets—knows that in his very marrow. He writes in times of joy and darkness; on slow, calm mornings and desperate nights. He also knows what poetry cannot do: it can’t save a marriage or reverse a tragedy, nor can it halt the slow grind of time. Poetry’s power is in the page: it paints the story of a moment that exists only when it is lived, conjured, or captured again in memory. Poets are the memory-keepers.

Hirsch’s memory-keeping began when he was a beak-nosed boy in Chicago, writing down his thoughts and feelings without a trained eye for form or craft. He traded form in those years for raw passion, which he recalls lustily in later poems:

I’d give anything to find that birdy boy again

bursting out into the dusky blue afternoon

with his satchel of scrawls and scribbles,

radiating heat and singing with joy.

He developed his prowess at Grinnell College, as a star football player and as an English major. “I solidified my vocation [as a poet] at Grinnell,” he says, sitting in his wide office at the Guggenheim Foundation, his back to the incredible expanse of New York framed in the windows. “And it’s never wavered.”

From there he began picking his way down the poet’s path, starting with two years of Watson Fellowship-funded travel and exploration in Europe. Once back in the States he kept on writing, taking a semester at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop that was aided by a grant from the NCAA’s Postgraduate Scholarship Program. Soon the private world of a poet expanded to include the wider world of cultural study. Before spending two decades teaching literature, folklore, and creative writing—first at Wayne State University in Detroit and then at the University of Houston—he entered the PhD program in folklore at Penn.

The University proved to be a “tremendous intellectual hotbed” for Hirsch, who was enthralled by the cross-disciplinary nature of the folklore and English departments, where poetry and cultural inquiry seemed to percolate in equal measure. (His doctoral dissertation, under the late English professor Daniel Hoffman, was a study of W.B. Yeats and Irish folklore.) Other Penn scholars of folklore and anthropology, such as Dan Ben-Amos CGS’97 (now professor of folklore & Asian and Middle Eastern studies), John Szwed, and the late Dell Hymes, also impressed him with their deep interest in poetry—“but poetry all around the world, and the poetry of everyday life,” he explains. “And poetry as it related to culture.”

That dedication to the cultural breadth of poetry stuck with Hirsch, whose 1986 collection Wild Gratitudewon the National Book Critics Circle Award, and whose passionate commitment to the art form earned him a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” in 1998. In 1999 he channeled his passion and his craftsmanship into How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love With Poetry(Harcourt Brace), and earlier this year he published A Poet’s Glossary (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), a thick compendium of the roots and branches of poetry, from its earliest forms to newer and ever-more experimental varieties.

Poetry can sometimes feel insular, focusing on the details of a single day, or a wrinkled leaf, or the face of a friend. But Hirsch’s new book illustrates the reach that poems have had in human life: from ancient Greek epics to timeless lullabies to work songs in the American South. His critical work seeks to address those poets who have just begun to scrawl and scribble, “a young person who is on his or her own, in some part of America where it’s lonely to write poetry.”

Though a reference book may strike some as anachronistic in the age of Google, Hirsch wants A Poet’s Glossary to be read as a book, nestled in the lap of the veteran poet or the uninitiated beaky boy. He wants to make the act of reference a chance to read, to flip through pages and let the eyes fall upon unrelated alphabetical entries. Google may direct you to a precise definition of a sestina, but it will not remind you that riddle and satire are also poetic forms, nor will it steer your eyes to the Gypsy seguidilla, which “begins with a terrible scream that divides the landscape into two ideal hemispheres.” This randomness of discovery delights the reader of any well-crafted compendium and ignites an interest in poetry for its own sake.

On September 2, Hirsch published a deep and highly personal work that speaks to the power of poetry in his own life. After his 22-year-old son Gabriel died suddenly in 2011, Hirsch rescued himself through writing.

For three years he gathered the memories of Gabriel still living inside him and in those who knew and loved him, and out of that hundred-plus page dossier he crafted a single, book-length poem. Gabriel: A Poem(Knopf) has three parts: it speaks to Hirsch’s grief as a father, to his son’s life and his own alongside it, and to the many other poets who have continued to live and to write after shattering loss. He hopes that the personality and spirit of his son will shine through the book.

“Because he was so outrageous, so funny, so odd, really,” Hirsch explains, the twinkle of a smile emerging from some deeper place.

“A lot of my poems have to do with rescuing something from oblivion,” he adds. “A person, a memory, an experience. And transforming it. Something you don’t want to die.”

—Violet Baron

I love the desciption of Hirsch as a “memory-keeper.” Article makes me want to read Hirsch’s poetry and buy his reference book. Well done!

Lovely, spare and evocative!

Befitting the great poet and thinker…