Twenty-five years after she helped launch the original Nicktoons, Linda Simensky is still deciding what millions of kids watch on TV—and teaching Penn students who grew up loving the shows she developed.

BY MOLLY PETRILLA

Illustration by Roman Klonek

Photography by Justin Tsucalas

The Powerpuff Girls were fighting again. Voices squeaking and cartoon eyes bulging, Buttercup, Bubbles, and Blossom flew at a bad guy, throwing out kicks and punches.

Linda Simensky C’85 and her two-year-old son, Ethan, watched from the couch.

The superhero sisters weren’t just on the family TV back then. They were all over the house—splashed across posters, printed on T-shirts, molded into action figures, even on a cookie jar. Simensky had fought to get Powerpuff on the air as an executive at Cartoon Network. Ethan didn’t know that, but he could tell from all those mementos that the sisters were important.

As the girls sparred with an enemy on screen, Ethan turned to Simensky and punched her shoulder. He smiled up at her.

“I was like, ‘Huh, he just learned that from watching them,’” Simensky remembers. “That’s not good.”

It was 2002, and she’d been working in animation for well over a decade. She had helped build Nickelodeon’s cartoon department in the early ’90s (the Doug, Rugrats, and Rocko’s Modern Life era) and worked at Cartoon Network since 1995. Rather than sketching characters or writing scripts, as an executive she helped creators refine their ideas, test out their pilots, and ultimately put their shows on TV.

Simensky loved making kids laugh, but she hadn’t thought much about how else cartoons might affect them. How a kid who hears Ren call Stimpy a stupid idiot enough times might think that’s a good nickname for a friend. How a toddler watching superhero sisters fight a bad guy might try landing his own punch.

Sitting with her son that day, “I started looking at TV through the eyes of a mother rather than just a cartoon-maker,” she says. “I remember thinking, ‘If I’m going to make shows, I need to make something that’s impactful and important.’”

So she went to PBS, where she’s been in charge of children’s programming since 2003.

The move shocked many in the industry, but it wasn’t the first time Simensky, who now teaches animation-history classes at Penn, grooved to the strum of her own sitar. (No, really, she used to play one of the Indian lutes on College Green sometimes.)

Guided by gut instinct and personal taste, she’s made a career out of divining what kids want to watch. Her work at Nick and Cartoon in the ’90s helped coax teens and adults back to cartoons and made animation zeitgeisty again. At PBS, she’s managed to keep kids’ attention despite the siren calls of Netflix and iPads and XBox.

She also has a pretty cool office.

Where should you look first inside Simensky’s stuffed, technicolor room at the PBS headquarters in Arlington, Virginia? Maybe at the bowl of marbles or the Wallace and Gromit figures. The miniature globe collection or the succulents on the window. The Roz Chast originals or the doodle a coworker made in a meeting, now hanging framed on the wall. The photo of her last office, in which there’s a photo of the office before that, and on and on in a decades-long, Escher-esque joke with herself.

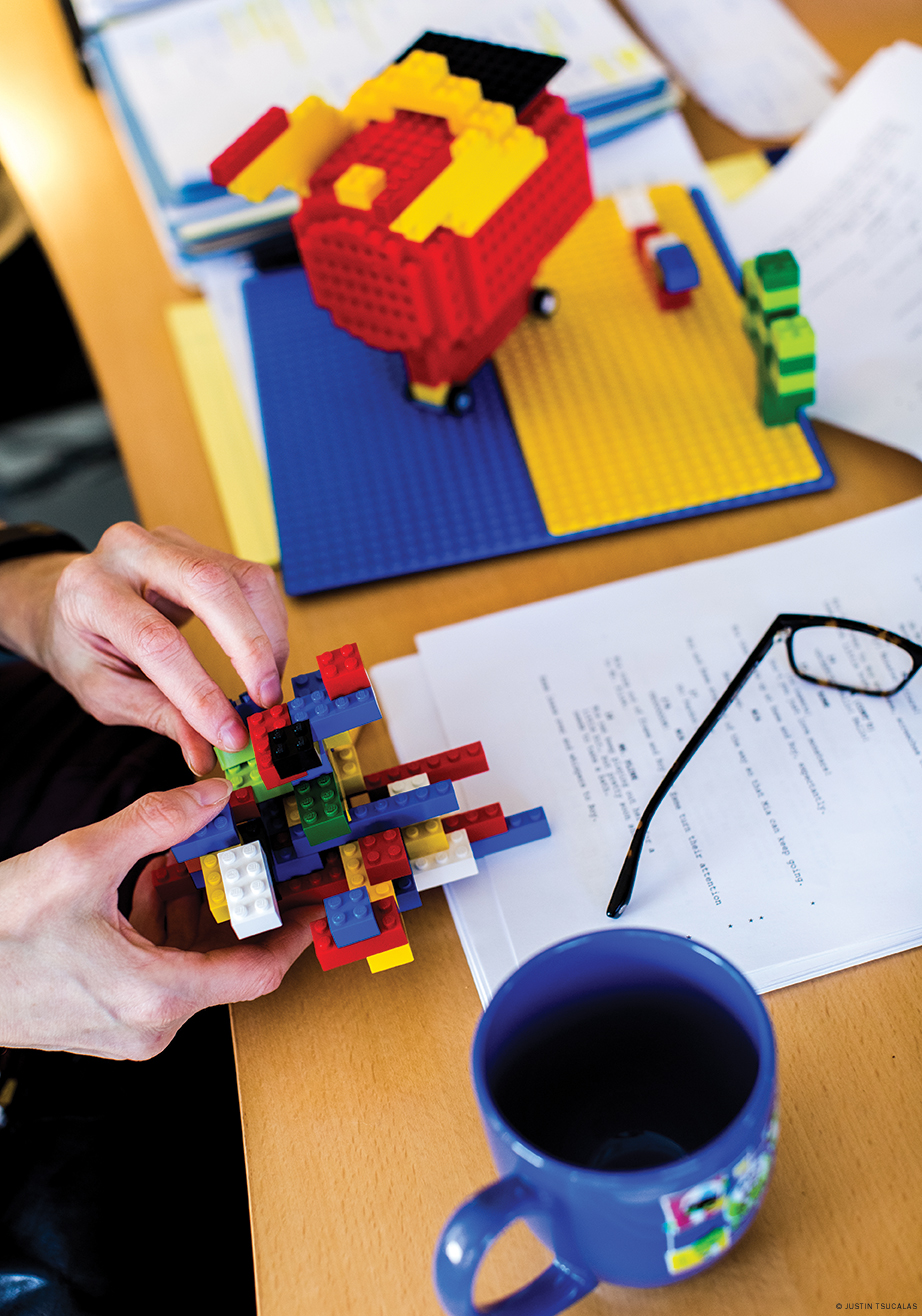

Maybe at the glass bowl of Legos, which occupy her hands during meetings. She’s had them for decades and recommends it: “Your productivity will go way up.”

“Over here we’ve got some Pez,” Simensky says, pointing out a jumbo size Snoopy dispenser. “There’s Beaker from The Muppets, and Bugs Bunny, and some Beatles. Astro Boy. And I have a whole collection of the Fisher-Price Little People from the ’60s and ’70s.”

Reminders of her current work are tucked in, too. At PBS she decides which shows will make it to air and works with the people who create them. There’s also some lurking behind one-way mirrors during focus groups involved in the job.

On a recent weekday, almost every show that aired between 6:30 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. on Philadelphia’s PBS member station WHYY arrived during Simensky’s tenure. Her office marks some of those shows with a parade of Dinosaur Train characters in front of a framed picture from Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood. Across the room, a stuffed animal from The Cat in the Hat Knows a Lot About That tops a shelf.

It’s a massive display, impossible to digest all at once. A swirl of colors and characters that’s somehow neatly organized and chaotic at the same time. Craig Bartlett, the creator of Hey Arnold!, Dinosaur Train, and Ready Jet Go, took a panoramic shot of it all with his phone the last time he visited Simensky.

“Going to her office is like going to this hilarious shrine of weird animation collectibles and cool animation art,” he says. “When she has to move out of there some day, she’ll have a huge job packing out.”

“I’ve never dabbled in tasteful,” Simensky says midway through a tour of her workspace. Taste aside, it must be distracting to have so many things clamoring for her attention all the time. “Not at all,” she says. “I would be very distracted if it were empty in here.”

She says it’s not unusual for people in animation to have offices filled with stuff. “We’re all visually oriented and it’s sort of how we communicate,” she adds. “It’s how we think. It’s like the insides of my brain are on the wall.”

Simensky’s brain, much like her office, has been swirling with animated characters since toddlerhood. Her baby book includes the note that she “loves to watch cartoons!” in the age 3 section. When she learned to read a few years later, it was to decipher Peanuts strips and conquer TV Guide . “I knew that if you could read those two things, that was power,” she says.

Growing up in Union, New Jersey, not far from the Newark airport, Simensky would hustle home to watch old Bugs Bunny cartoons after school. In eighth grade, she started telling people that she wanted to write scripts for Bugs someday. “Then I learned Bugs Bunny had not been in production for quite some time,” she says.

While animation experts call the 1930s, ’40s, and early ’50s a golden era for cartoons, many write off the next three decades, including the years when Simensky was a kid. That’s when cartoons stopped having broad appeal. They ran on TV at times only kids were watching, with few traces of the carefully crafted, high-budget artistry that people of all ages had loved in movie theaters.

“Nobody really cared about animation, nobody really talked about it,” Simensky remembers. “By the time I was in my late teens, there was a real sense that animation was for little kids. Watching cartoons after I was past my teens seemed like a big act of rebellion at that point.”

But Simensky liked what she liked. At Penn she’d unwind with old Bugs Bunny shorts. A favorite, “Little Red Riding Rabbit,” sends Little Red off to grandma’s house with a familiar rabbit to stew.

She majored in communications and took a sitar class for five semesters. “Sometimes we’d go outside and play and everyone would look at us kind of weirdly,” she remembers. She didn’t care. She loved learning the instrument and meeting other students who were as Beatles-obsessed as she was.

Simensky told classmates she wanted to make cartoons someday. When someone asked what she was doing at Penn, a school with no animation department, she shot back: “Developing a sense of humor.”

On August 11, 1991, exactly 25 years ago this past summer, Simensky lifted her glass inside a Mexican restaurant in Greenwich Village and toasted a new era of cartoons.

She’d gone to her 10-year high school reunion the night before, been asked “What do you do?” by former classmates. She said she worked in animation at Nickelodeon. They looked confused. Nickelodeon didn’t make cartoons. “If you watch tomorrow, you’ll see what I’ve been working on,” she said.

The next morning, a Sunday, Nick premiered its first original cartoons in a single “Nicktoons” block: Doug, Rugrats, and The Ren and Stimpy Show. Simensky watched the broadcast in New York with Nick executives and the Doug creative team.

She had been out of Penn for four years and working in scheduling at Nickelodeon—making shows start on time using a computer that backed up via tape deck—when the network formed an animation department. Simensky had been clear about her cartoon obsession since she started at Nick. “Other than being really interested in animation, I didn’t really have any of the skills needed” to develop shows, she says. “But I was there, I knew the Nick brand, and I knew what I liked.” She became employee number two on the new two-person Nicktoons team.

Cartoons hadn’t improved much by the time she left Penn in 1985. Popular shows like The Transformers, The Care Bears and G.I. Joe were often, as Simensky wrote in an essay for the book Nickelodeon Nation, “merely half-hour commercials for the properties they featured”—and adults still weren’t watching them.

She points to three developments in the late ’80s that began reviving animation and clearing a path for the Nicktoons. Who Framed Roger Rabbit? became a hit movie in 1988; the Simpsonsgot their own show in 1989; and The Little Mermaid was nominated for a Best Picture Golden Globe in 1990. “It suddenly seemed that animation was ‘hot’ again,” Simensky wrote in her Nickelodeon Nation essay.

With their brand-new characters, gender-neutral appeal, and focus on “kid empowerment,” the Nicktoons promised something fresh. Most ’80s cartoons followed the Hanna-Barbera art style, but the Nicktoons were recognizable even from a single background frame. There were Doug’s soft curvy lines,Rugrats’ purple-heavy palette, and Ren and Stimpy’s—well, as an animator says in Slimed!: An Oral History of Nickelodeon’s Golden Age, “It was like somebody had slipped [creator John Kricfalusi] a tab of acid or something.”

All three shows connected with audiences—mostly kids, but some adults began watching, too. Their ratings ballooned. The characters showed up on the fronts of T-shirts and backs of jean jackets. Soon Simensky was developing a fourth Nicktoon, Rocko’s Modern Life, with creator Joe Murray, and working with Craig Bartlett on the Hey Arnold! pilot.

“We were kind of making it up as we went along,” she says of those early Nicktoon days. “No one was really making stuff like this, so we were just kind of guessing about what might work.”

But as the guesses paid off and the Nicktoons’ success grew, Simensky felt pulled toward a new cable network that was running cartoons 24 hours a day.

She bumped into Mike Lazzo, then the vice president of programming for Cartoon Network, at an airport baggage carousel in New York. As they waited for their suitcases to slither down the chute, Simensky told him how much she liked his network. Eventually they met up for dinner and talked for five straight hours about cartoons—not Cartoon Network, just cartoons.

Simensky moved to Atlanta in 1995 and started working for Lazzo at Cartoon Network. Reminders of that chapter—which lasted until she went to PBS in 2003—are sprinkled across her current office: action figures from Dexter’s Laboratory, a Powerpuff Girls skateboard, Samurai Jack mementos.

Like Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network wasn’t making its own shows when Simensky arrived. That meant she got to “start building again” as she had at Nick. Again she shepherded new shows from pitch to pilot to series. By the time she left Cartoon as head of original animation, the network had produced multiple hits.

Paul Siefken, who worked with Simensky at Cartoon Network and PBS, and now oversees content production and management for The Fred Rogers Company, has a simple explanation for her track record: “She knows how to get the funny out of people.”

Siefken says TV execs will often make suggestions for how something could be funnier, which drives creatives crazy. “She knows that,” he says, and instead dishes out feedback that leaves artists invigorated rather than frustrated.

That’s why Bartlett has followed Simensky from job to job, network to network. He says some executives give notes just for the sake of saying something. Others look at a script or storyboard and “take the edges off of it—smooth it out so it’s less weird or whatever.” But Simensky “gives me a ton of rope,” he says. “If she thinks something works, she’ll just leave it alone.” Like season two of Dinosaur Train, for instance. She told him there were no notes and added, “I’ll get out of your way.”

More than 30 years after she took classes in Bennett Hall, at the corner of 34th and Walnut streets, Simensky now stands inside one of its classrooms, facing her own students.

Jiminy Cricket is paused on a screen behind her. She warns the class that there have been some technical difficulties with the DVD player lately. “But don’t feel bad for me,” she deadpans, “don’t take pity on me.”

She tells the class that when she was a kid, Disney was for squares. “We were groovy eight-year-olds,” she adds. “We didn’t want to be seen watching Disney.”

The class giggles at this, as they do when Simensky delivers dry one-liners throughout the three-hour class. (“Pinocchio is like your annoying cousin who you have to keep bailing out of jail, and you’re Jiminy Cricket” lands especially well.)

“There’s a lot of laughing in that class,” Diana Gomez, a College senior who has taken several courses with Simensky, says a few days later. “And it’s the nice, natural kind of laughing—not the forced, give-me-an-A kind of laughing.”

Amy Jordan, the professor and associate dean for undergraduate studies at the Annenberg School who co-edits the Journal of Children and Media, remembers inviting Simensky to her 50-person class, Children and Media, for a guest lecture in 2012. Simensky had a broken leg at the time. She came anyway to talk about her work at PBS.

“I introduce her and she starts talking without a single note, without any PowerPoint slides, without any audio/visual, and she had that audience of students captivated,” Jordan says. “It’s a gift to be able to do that.”

In 2013, the Cinema Studies Program asked Simensky to teach Contemporary Issues in Animation. She’s come back every fall since to unravel the history and current practices of animation for Penn students. This semester’s course is called The Animation of Disney, and it’s cross-listed as an English, cinema and media studies, fine arts, or art history course.

On Monday afternoons, Simensky leaves PBS early and takes the train from DC to Philly. She walks over to campus and gets in front of her class, thick curly hair spilling down her back, a FitBit strapped to her wrist. Her voice is quiet and low, remarkably close to Daria from the old eponymous MTV cartoon. It’s distinct enough that several friends, including Beavis and Butthead creator Mike Judge, have asked her to perform characters on their shows over the years. She’s had to turn them all down because the acting part doesn’t come as easily as the voice does.

She doesn’t wear a suit. She doesn’t use PowerPoint and rarely looks down at her notes. “I want to make this clear,” Jordan says. “It’s not that she doesn’t prepare. She prepares extensively. It’s just that she needs no aids to convey what she wants to convey.”

Some of that may be natural teaching talent, but it’s also because Simensky has been working in animation longer than her students have been alive. As her crammed office makes clear, she is a fan of the art form itself—not just the shows she’s worked on but Bugs and Snoopy and Beaker, too. On LinkedIn, her profile photo is a cartoon drawing of her face.

Bartlett says that’s what makes her so good at finding hit shows. “She brings a really deep awareness of the history of cartoons and a love of cartoons,” he says. “A lot of executives you meet in this business don’t seem to particularly love cartoons. They’re just giving notes, trying to make sense of what they’re putting out. Linda’s a fan of the work.”

Many of her current students grew up watching the shows Simensky developed at Nick and Cartoon Network. Gomez says Powerpuff Girls was her favorite cartoon as a kid, so knowing that her teacher helped get it on the air “brings a whole different weight” to her lectures.

Among Digital Media Design students, many of whom continue on to work at high-profile animation studios like DreamWorks or Pixar or Disney, Simensky’s is “one of the most beloved classes,” says Amy Calhoun, DMD’s associate director.

Jeremy Newlin EAS’13 GEng’14, now a technical director at Pixar, took Simensky’s class his senior year, and he says it was one of the best courses he took at Penn—partly because it let him think deeply about animation without actively making it, but mostly because of Simensky.

“Our [DMD] professors in general are either computer scientists or artists,” he adds. “Linda’s a producer. There’s something special about hearing that perspective.” When Simensky taught a History of Computer Animation class two years ago, she says the class was about half DMD students.

Last fall she brought in some of the old Nickelodeon pilots that never made it to air. Next year, she’s planning to teach a class focused specifically on TV animation—and again integrate her past work. She admits that it’s “very trippy” for her early work to now be a history lesson.

As a former student told Simensky, referencing a genre that dates back to 1900, “You are the history of animation.”

“I said, ‘I know you mean that as a compliment,’” Simensky remembers, “‘so I’m going to take it as a compliment.’”

One of PBS’s newest additions, Nature Cat , opens with an earworm theme song, sung at almost-off-the-rails speed:

We’re climbing up the trees now.

We’re swinging through the breeze now.

We’re getting muddy knees now

With Nature Cat.

Fred’s an indoor cat who morphs into his alter ego, Nature Cat, as soon as his humans leave for the day. He goes on outdoor adventures and gets into more slapstick situations than the dignity of a real feline would ever permit. (In a single episode he runs smack into a tree and also gets spritzed by a skunk, stung by a bee, and chewed up by mosquitoes.) The characters’ voices come from Saturday Night Live stars past and present—experts at making people laugh. As Nature Cat co-creator David Rudman told Channel Guide Magazine last winter, “We wanted to do Looney Tunes with a nature curriculum.”

Between the humor and classic animation style, the show looks and sounds like something Simensky might have put on Cartoon Networkback in the late ’90s, but with science lessons and an underlying message that nature is cool. The show sums up what she has tried to do at PBS since she got there: train her eye for entertainment on an educational mission.

When she arrived in 2003, Barney & Friends and Teletubbies and Clifford the Big Red Dog were among PBS’s top offerings for kids. Simensky wondered what had happened to funkier shows like The Electric Company, the broadcaster’s sketch comedy series that she’d loved in the ’70s.

During her interview at PBS, she suggested funnier TV that focused on academic subjects rather than building social-emotional skills. She got the job.

The first new show she brought to PBS came from fellow Nickelodeon alum Mitchell Kriegman, who created the wacky live-actionClarissa Explains It All in the early ’90s. Simensky has brought in more Nick show-makers since then, including Craig Bartlett (Hey Arnold!) and Joe Murray, who created Rocko’s Modern Life at Nick and is now working on a show for PBS called Luna Around the World.

Simensky is aware of how her audience has changed since she moved to public television. Many of the kids watching PBS stations come from low-income families. They don’t have cable, or a personal iPad. They can’t tune into Nickelodeon and Disney or watch cartoons on Netflix. They don’t always get to see the newest Pixar blockbuster in theaters.

“They end up watching us,” she says, “and they shouldn’t be penalized for that. Everyone should have access to funny programming.”

When Nature Cat premiered last November, some parents wrote in to say that it couldn’t possibly be educational. It was too focused on laughs. That made Simensky laugh herself. “I’d always dreamed of the day someone would complain that a show I’d worked on was too funny,” she says. Now Nature Cat is one of PBS’s top five shows.

Cory Allen Gr’00, the associate director of research at PBS from 2000 to 2007, says Simensky helped reinvigorate the nonprofit’s programming. Before she got there, “I think there was a sense among some people that a PBS show must look a certain way or not have humor, not have an edge,” he says.

At the same time, Jordan says Simensky’s choices at PBS acknowledge how perceptive kids are. “She knows that the content we give children shouldn’t be talking down to them or pandering to them, but challenging them,” Jordan adds.

If that Powerpuff moment with Ethan started the shift, then making educational TV has fully transformed Simensky into a curriculum convert. When friends hand her their pitches for other networks, she’ll read them and think, But what is this about? “I’ve gotten so used to shows having a purpose that it’s weird to look at ones that are just funny,” she says. “Though to me, Odd Squad and Nature Cat are just as funny as anything I’ve worked on in my other jobs.”

But unlike at those other jobs, Simensky doesn’t get to make hits anymore. Not because she works for PBS, but because there are so many series out there and so many places to watch them.

“Clearly the definition of ‘hit’ now is that you’ve made it past the first season,” she says. “No show gets the amazing ratings that something like SpongeBob SquarePants got. It’s just not that world anymore.”

Actually, is show even the right word? PBS Kids calls itself “an educational media brand.” Series like Nature Cat aren’t only on TV. They’re apps. They’re on the PBS website with games and video clips and DIY projects. “We say TV as shorthand,” Simensky says, “but really we’re making content.”

“It’s a transmedia experience,” adds Jordan, who studies media’s effect on kids. “And under Linda’s leadership, [PBS] has recognized that the landscape has changed. She’s been very cutting-edge with it.”

Simensky sees this multi-media revolution as a good thing—“a great way to be in a lot of places,” she says. As a kid, she missed the Brady Bunch episode that introduced Cousin Oliver. There was no chance to catch up, so instead she tuned in the next week and sat there wondering who this new little kid with glasses was. Now kids can watch anything they want any time they want to, and they can keep interacting with it between episodes.

But even as she puts out wildly varied content—shows with their own apps and games, shows with puppets, shows with live actors—Simensky remains an animation junkie at heart. She loves The Simpsons. She watches Phineas and Ferb and Gravity Falls. Her kids came home from school one day and found her home sick watching an episode of the PBS cartoon Arthur.

“Are you watching that for work?” they asked.

“I said, ‘No,’” Simensky remembers, “I’m watching Arthur ’cause it’s funny.”

Having known Simensky for more than 20 years, Siefken says he can’t picture her working in any other field. “It’s not really a choice for her,” he says. “It’s not what she does. It’s who she is.”

Just ask the Looney Tunes monster and Lisa Simpson figure perched over her desk.

Molly Petrilla C’06 blogs on arts and culture for the Gazette and writes frequently for the magazine.