Philanthropy at the end of a fist. Grad students beyond thunderdome. Chin-rattlers. Brain-shakers. Welcome to Fight Night.

By Trey Popp | Photography by Candace diCarlo

Sidebar | The Alumna Behind the Blue Horizon

Before he stood in a ring edged by 1,200 frenzied spectators, boxing gloves slicked with sweat, white trunks speckled with the blood of his charging opponent, Donal McElwee worried that his manager would fail to deliver the dwarfs.

It was going to be the Wharton welterweight’s only bout of the year. All his friends would be there. He didn’t care if it cost a thousand bucks. The Irish native was dead set on having leprechauns in his entourage.

“It’s a matter of luck,” McElwee said in a dressing room, his brogue heavier than a sock full of stones, as the opening bell of Philly Fight Night drew near. “You need the little people in your corner when you’re fighting. I feel 10 times more confident with them than without them.”

Already, the belly of North Philadelphia’s legendary Blue Horizon boxing hall was quaking with noise. The 900 advance tickets allotted to Wharton had sold out in 20 hours, at $35 and $50 a pop. Now Penn Law students were streaming through the security pat-downs to support their own contingent of pugilists. There were six bouts on tonight’s card. Ten men and two women were about to climb past an EMT and a fight doctor to risk more than their pride in three rounds of combat.

The gate take, plus a handful of corporate sponsorships, would amount to a $55,000 donation to the Boys & Girls Clubs of Philadelphia. At the moment, however, McElwee’s entourage seemed to be the subject on everyone’s lips.

“I heard he’s hiring midgets as leprechauns,” said Wharton first-year Dana Scardigli, all but spilling out of the minimal attire required of an official ring girl. “I don’t know how I feel about that.” Then she disappeared into the giggling commotion of the ring girls’ ready room, where someone cried out, “More rouge!”

Across the way, grad students wearing sweatpants and sneakers tried to whittle away such distractions.

James “Playboy” Williams plucked out a pair of iPod earbuds to share his strategy for the third fight. “Knock his nose in, then his eye sockets, then his cheekbones,” the student of entrepreneurial management declared. “All in round one.” Perhaps confidence would get him further than his 0-1 lifetime record. “I’ve boxed once, in Thailand,” Williams confessed. “I was just on holiday there and wanted to fight. So I got myself into a fight in Chaweng Stadium. I lost.” But this time he had trained. And there was no question that his head was in the game. It bore the long spike of a freshly shaved mohawk, rendered “by popular request—of three people.”

Third-year law student Bill “The Big Show” Stone looked up from his wrist tape to consider whether he had ever done anything this crazy—or done anything at all, for that matter, in front of 1,200 people screaming their throats out. “If I have, I was a lot better at what I was doing than what I’m doing tonight,” he said. “I’m just going to try to conserve my energy, make it to the end of the fight, and try to land some haymakers if I get the chance.”

Elena “The Russian Bombshell” Aidova, a second-year law student, allowed that her opponent was “a nice girl.”

“But that’s all out when we get into the ring,” she quickly added, for there is no boxing without bluster. “I’m going to go for the head, go for the knockout, and walk out seeing her on the floor.”

EVEN RING FIXERS GET THE BLUES

Philly Fight Night is the brainchild of three Wharton students who went to the Blue Horizon on a lark one night five years ago. When they came out, R.T. Arnold WG’05, Schuyler Coppedge WG’05, and Dave Birnbaum WG’05 couldn’t shake the venue from their minds. Carved out of a row of brownstone mansions whose facades date to 1865, the smoke-stained auditorium has been called the best place in the world to watch boxing by none other than Ring magazine. The ring sits in a cavity taller than it is wide, framed by wooden balconies that dip down so close to the ropes that a spectator could almost lean over and land a bareknuckle punch.

In the city of Joe Frazier and Rocky Balboa, where “fighters come out of the womb knowing how to throw a left hook”—as local sportswriter Bernard Fernandez once put it—the Blue Horizon is a landmark unlike any other. It boasts of having hosted 30 world champions since opening in 1961. Stand in the hall when it’s empty, and the idea of 1,200 people cramming inside makes you wonder how much the fire marshal gets bribed. Experience a packed house, and you’re bound to fall under the spell that gripped Arnold, Coppedge, and Birnbaum.

“We kept talking about it for a week or two afterwards,” Arnold recalls. “So we came up with the idea that maybe we could convince Penn grad students to get in the ring for charity.”

Choosing a beneficiary was a cinch. The Boys & Girls Clubs of Philadelphia serve some 15,000 local kids, and sports are a major component of their programming.

Recruiting boxers turned out to be surprisingly easy as well. The trio managed to coax 16 fighters—experienced and otherwise—onto their card in fairly short order.

The volunteer pugilists, of course, would have to do considerably more than just skip rope until it came time to lace up their gloves. Each one committed to a demanding training and sparring regimen supervised by Cliff Johnson, a former boxer and longtime coach who had recently become involved with the Penn Law and Wharton boxing clubs. Johnson’s task was arguably the tallest of all, for he would be Fight Night’s matchmaker, as well as its referee.

Yet Arnold and company still faced a daunting order: getting a critical mass of their classmates to a part of town where few had ever set foot, to watch a sport that almost none had ever paid money to see. It was the same challenge every promoter faces, only no ring fixer in history has been deluded enough to rely on grad students to churn turnstiles.

By noon on the big day, it looked like the trio was about to learn why.

“We had sold about 200 tickets,” Arnold says. “I mean, hardly anything. We were looking at each other. We weren’t even sure we were going to be able to cover our costs, let alone give any money to the Boys & Girls Clubs.” A couple hours before show time, Arnold was pulling down folding chairs. Fight Night was bleeding before the first punch had been thrown.

Then, minutes from the opening bell, a huge crush of people hit the box office. Eight or nine hundred bodies poured inside. Yet the mood was still uncertain, skeptical even. No one seemed sure what exactly the night had in store.

“People didn’t believe that the students were actually going to fight,” Arnold remembers. “They thought it was going to be a joke, or some sort of performance. No one could really get it. And when the first fight started, and they realized that it was actually for real, the place just blew up.”

Below, each fighter’s entourage.

DO DEAD MEN DRAW BLOOD?

On February 28, 2009, the Blue Horizon’s floor literally trembled beneath a sellout crowd as Praveen “The Baby Face Assassin” Lingathoti made his way to the ring in a wooden coffin borne by four hooded figures dressed like Benedictine monks.

An 18-year-old Boys & Girls Club member named Jessica Sledge had just kicked off the fifth annual Fight Night with an object lesson in guts, belting out the national anthem unaccompanied by background music—or the duet partner who had been struck songless by the room’s unreal voltage. Now it was Lingathoti’s turn to face the glare. It would be an uphill battle for the Wharton second-year. He’d be giving up 20 pounds and three inches in height to Al “The Truth” Taj CGS’01, a third-year law student who entered the arena wearing an orange prison jumpsuit and handcuffs.

Escorting Taj was a quartet of what can only be called “lady cops.” Navy blue mini-dresses, eight-point police caps, black boots to the knee. Forget about the right to an attorney. Is there a right to be arrested by the cast of a midnight feature on Cinemax? No wonder Donal “The Lethal Leprechaun” McElwee felt pressure to live up to his ring moniker. An amateur fighter might be forgiven a disappointing bout, but his entourage had better give the crowd its money’s worth.

After the hoopla of their arrival and the ding of the bell, the opening combatants circled the ring tentatively. Their first clash turned quickly into an embrace. Feet shifted, arms flailed, and the two bodies locked together again. So the clinch-heavy theme of the first fight was set. The convict landed no blow worthy of a felony rap sheet. The assassin managed a few valiant flurries and bloodied his mark’s nose, but spent too much time leaning away from the action. Bottom line: neither man managed to send out the other in Lingathoti’s raw-pine conveyance. At the end of three rounds and a 2-1 split decision, the referee raised Taj’s clenched fist. The throng bellowed and booed. Penn Law 1, Wharton 0.

To even the score for the MBA side, Ryan “Rampage” Berger would have to go through all 210 pounds of Bill Stone, the biggest man on the card. It was hard to know what to make of this match-up. Berger, who once broke an ankle dancing around a make-believe jump rope at a wedding reception, had been playing it coy in the run-up to Fight Night. “No matter how much preparing I do, I’ll still be lost in the ring,” the New Orleans native said a month before his bout. “But hopefully the other guy will be too.”

The other guy wasn’t. Stone came out at the opening bell with haymakers still on his brain, stunning his smaller opponent with a shot to the nose that drew blood halfway through the first frame. As the clock expired on the opening 90 seconds, Berger looked astonished. “When you’re sparring,” he said later, “one and a half minutes seems to last forever. But this was totally different. When the ref said Round!, I was blown away. It felt like we’d just started.”

Only after Stone landed a second stiff blow in the next round did the Wharton first-year snap out of his daze, driving the bigger man into the ropes three times in rapid succession even as his own headgear slipped off. The Wharton contingent roared as the tide seemed to turn, and Berger blew the lid off in round three with the first proper wallop of the night.

“I don’t know where it came from,” he said afterward. “It wasn’t anything I’d planned. I just let my arm go. Before I even knew I had done it, the crowd was going nuts and he was going back. I had a good feeling then that if he didn’t come out of the standing eight count and put me on the ground, the fight was mine.”

The final bell sounded with both men still standing. The judges were unanimous: Berger had evened the score.

It wasn’t until the third fight, however, that the crowd fused into one primal mass and fell off its collective rocker. Tommy “1-2-3” Forr got cornered before the bell even rang. The rugby players in James Williams’ entourage backed him against the ropes with a Maori war dance—the haka performed by the New Zealand All Blacks before international matches.

It did not intimidate the second-year law student. Forr, who carried a 7-1 record as an undergraduate at Notre Dame, had scored a three-round victory in last year’s Fight Night.

The bell rang. Forr came out of his corner with leonine grace, feet sweeping over the mat in a balletic whirl, hands quickly recoiling after each probing jab. Williams moved almost as fluidly, but heaved more of his body with each lunge. A shot to his midsection caused him to stagger, yet it was Forr who first lost his balance, hitting the canvas after a glancing blow to the head.

He bounced back to his feet in less than a second, answered the ref, and flew back at Williams like a pinball from a paddle. Williams stepped into his charge. Clearly neither fighter would be playing it safe. A pulse of energy rippled out from the ring as Forr reclaimed the offensive, doubling Williams over next to the ropes. The throng came unhinged. The sound of the bell was almost inaudible five feet away from the clapper.

The next time it rang would be the last. Again Williams and Forr charged into the center of the ring with breathtaking speed. They clashed and spun, far from the corners, until one punch froze the action for good. Forr tossed a left jab that exposed his head just long enough for Williams to power through with a devastating right cross. The strike sent Forr’s head bobbling as though his neck was made of springs. His knees buckled. Williams followed with a gentle left hook that almost caught nothing but air. Forr was already falling away, his legs splayed fore and aft as his back collided with the mat.

“I have no doubt that he had me on points in both rounds,” Williams said later. “He was great. But my corner man said, ‘Throw the overhand right, and if you land that, he’s going down.’ So I listened.”

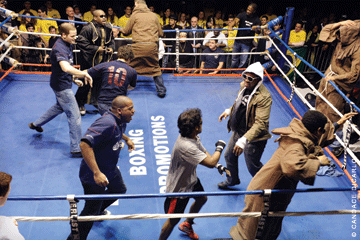

Forr rose to his feet more slowly this time, and walked to his corner. The referee looked into his eyes for a moment and then waved off the action. The judges held on to their scorecards; it was Williams by technical knockout. Wharton 2, Penn Law 1. The airspace above the ring suddenly filled with a spectator who had leaped out of the balcony in a lunatic victory dive. He thwacked the canvas on all fours and sprang up to embrace the victor. The hysteria of the crowd was total.

THE CHARMS OF SMACKDOWN PHILANTHOPY

Some people jog for charity. Others walk. Not long ago an American breast-cancer foundation staged a stroll-a-thon whose participants didn’t even have to get off the couch, deputizing online avatars to walk for a cure in cyberspace instead. Yet in the last five years, dozens of Penn graduate students have elected to take an actual physical beating to raise money for a cause. Why?

“It’s kind of ancient, in a way,” muses Lou Marchetti, an MBA student and one of this year’s organizers. “It’s a little barbaric, but not totally—there are rules. But it’s really just man-on-man, or woman-on-woman, with no one else to help them out in the middle of the ring. So your heart is racing for that person. Because whomever you’re rooting for, it’s them against their opponent, and if they lose, there’s some consequences of getting knocked out.”

For Wharton students, whose educational experience is often channeled through group cohorts and teamwork, there may be something uniquely appealing about the competitive purity of boxing’s every-man-for-himself dynamic. After all, boardroom victories can come in all flavors, including poisons that have none. The ring is a simpler affair. The field of combat is well lit. Your opponent can’t sneak up behind you. You can’t win by subterfuge.

Or maybe it’s just irresistible to do something that would all but spell doom in the post-graduation quest to impress some firm’s senior partners.

“For a lot of business-school students,” says R.T. Arnold, “they say, ‘This is a chance to do things I may never do again.’ There’s definitely a risk, but everyone I’ve spoken to who’s done it, whether they’ve won or they’ve lost, said it’s just a once-in-a-lifetime experience that they’re never going to forget.”

For others, it’s a chance to revisit a feeling that age will soon put beyond reach. “Look,” Tommy Forr said with disarming cheer after his loss, “I’d much rather do this than stand before the Supreme Court and make an argument. Any day. But God didn’t give me those gifts.”

The intensely local nature of Fight Night also scratches an itch that sometimes nags grad students who pass through town without really making a connection. “We want to show that Wharton is about more than just having kids run around Philly for two years,” Marchetti says. “You want to make sure you’re out there in the community, and not just doing your own thing.”

For the Boys & Girls Clubs, “$55,000 is a huge number,” says Al Molica, the organization’s chief development officer. “It’s the second-largest fundraising event that we’ll have over the course of the year.” And this year there was more to it than the money, he adds. “This year we had Lou, [fellow organizer] John [Buchanan], and some of the fighters come out to our Bridesburg club and work with our kids—sort of teach them a little bit about boxing, and present solid role models.”

“That was a lot of fun,” says Rick Springman EAS’02, a doctoral candidate in mechanical engineering. “We talked to a group of about 30 to 50 kids, aged maybe 7 to 11, about the importance of education and exercise. We kind of used boxing as a tool to emphasize the role of discipline.

“Then we got to work with them and show them some stuff, which I thought was funny,” he adds. “I was thinking about their parents, and how they were probably going to hate us for teaching their kids to box—because the first thing I would have done if I learned to box as a kid would probably be to box my brother when I got home. But the kids really enjoyed it, and I think we probably enjoyed it just as much.”

“That’s one of the most important things for us, that connection,” Molica says. “University of Pennsylvania kids are high-level folks. We want to give our kids an understanding of what they can aspire to be.”

THE CATS FIGHT, THE BULL BLEEDS, THE LEPRECHAUN GETS IN HIS LICKS

Insofar as aspiration requires courage, it would be hard to find a better example than Wharton’s Leeatt Rothschild. At five feet and two inches, she would have had trouble seeing the action from any row but the first. Yet she had a different problem when the referee signaled the beginning of bout four. Namely, she was in it.

In the absence of an official tally, it’s impossible to know if Rothschild threw more punches per second of combat than any other fighter of the night. Her rapid-fire, battering-ram approach to Elena Aidova’s belly made it seem like a strong possibility. She may have lacked Rocky Marciano’s deltoids or Mike Tyson’s dental attack, but Rothschild was a true swarmer.

Aidova’s response drove both the crowd and the referee wild: she simply grabbed Rothschild and threw her onto the canvas in the first round.

Duly warned, the law student went on to use her superior reach to fend off her smaller opponent, landing the occasional blow between Rothschild’s game charges. The bout ended in a bloodless split decision for Aidova, deadlocking the Wharton-Law tally at 2-2 in head-to-head competition.

The penultimate match pitted Wharton’s Adriano “The Bull” Blanrau against Springman. The engineering alumnus would be giving up 20 pounds to the big Brazilian, but had credentials to fill the gap. Springman was a two-time All-American wrestler as a Penn undergraduate.

Fight Night would give him a chance at a sort of crossover comeback. “It’s been about eight years since I competed. I’ve grown to miss that intensity,” Springman reflected afterward. “Pre-match, when you’re in that space where it’s just yourself, and you know you’re going up against an opponent, and it’s only the two of you out there … it really felt good.”

Blanrau gave him two and a half rounds to add to his recollections, but the ref called the bout for Springman ahead of the final bell. For the second year in a row, Penn Engineering’s lone pugilist notched a convincing win.

And just like that, it was time for what Donal McElwee had promised would be the spectacle of the night. “It’s the main event,” he’d declared at the outset.

“But you and your opponent are the smallest fighters on the entire card. What makes you the big draw?”

“Because I’m explosive. I can guarantee you I’ll be crowd-pleasing, and the guy I’m fighting is good.”

“Will there be small-statured men in your entourage?”

“We’ll see,” the 142-pound Irishman smiled. “It’s not as easy as you think getting those people on board. I’ve got my manager in charge of that. He spent many hours trying to get a hold of little people.”

To all appearances, that was more time than 149-pound Nathan Dyer had spent mapping his whole fight strategy. “Don’t get hit: that’s my strategy,” the Graduate School of Education student said in his dressing room. “If I don’t get hit, and I hit him once, I win.”

But appearances are deceiving. On the basis of a three-year-old press clipping, Dyer would be anything but timid in the ring. “In the only knockout in the first set of matches,” the Notre Dame Observer reported in 2006, “the referee stopped the fight in the second round to save freshman Jack Carroll from the beating he received from junior Nathan Dyer.”

If life were a boxing movie, McElwee and Dyer would have entered the arena towering over every man in it, and their battle would have ended in a come-from-behind knockout. But life is a bit weirder than that. And weirder still on Fight Night. Dyer ascended the ring clad in black shorts and quiet resolve. McElwee entered in a tartan kilt. Both men towered over two shamrock-covered members of the Irishman’s entourage, but the bagpiper was a head taller still.

The last bout went the distance. The fevered crowd no doubt wanted more. So when the referee raised The Lethal Leprechaun’s right hand in victory, bringing Fight Night V to a close, everyone in the Blue Horizon had a question to face:

Who’s ready to start training for next year?

SIDEBAR

The Alumna Behind the Blue Horizon

Boxing at the Blue Horizon goes back to 1961, but the venue itself has been on the ropes more than once in recent years. Perhaps no person has done more to keep it in business—and out of condemnation proceedings—than Vernoca Michael SW’72 GCP’74.

In 1994, Michael and business partner Carol Ray quit their jobs and took on $500,000 in debt to buy the Blue Horizon. What primarily attracted them were the building’s architecture and its potential to become a cultural hub on Broad Street, which Philadelphia was rebranding “The Avenue of the Arts.”

“I was supposed to be just an investor,” Michael says. She ended up being far more. She started a nonprofit educational foundation, helped to orchestrate a badly needed, $3.5 million renovation of the historic building, and became the first African-American woman boxing promoter in Pennsylvania. “From a legal standpoint,” she says, “I think there are now about four in the country.”

None of it was easy. A month after the purchase, the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections cited the Blue Horizon for dozens of problems, including fire and electrical code violations. Its new owners knew the building needed work, but hadn’t realized just how much. The city had promised $2 million for the Blue Horizon that year, but that line item never made it from the budget to the bank. Michael and Ray managed to scrape up enough money to patch up problems here and there, but more rounds of daunting code violations followed and at times it seemed like every fight at the Blue Horizon could be the last.

They kept at it, eventually pulling down a $1 million state grant and a $1 million low-interest loan from the Delaware River Port Authority to make the renovation a reality in 2002.

Since then, Michael has carved out an unusual niche in the male-dominated world of pugilism. “That proved to be challenging,” she says. “However, attending the University of Pennsylvania when I did, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, helped prepare me for that kind of thing.

“I had the experience of challenging larger institutions when it came to some areas of discrimination,” she explains. “In those days you had very few African Americans attending Penn. And Penn would make statements like, ‘We couldn’t find any qualified candidates.’ Well, you can’t find any qualified candidates if you’re not looking! So I had to challenge the school to step up to the plate and begin to find qualified candidates.”

Almost 40 years later, Michaels says Penn has been a longstanding partner to the Blue Horizon’s nonprofit arm, which provides job training, internship opportunities, and other social services geared toward preparing young adults for the “world of work.”

“Many people don’t know the kinds of things that we do with the students in the community,” she says. “They only want to see us from a boxing point of view. And I say to them, ‘We do boxing approximately 10 days a year; what do you think I do the other 355?’”

Of course, a lot of Philadelphia sports fans might consider Michaels’ efforts to keep the punches flying in this hallowed hall a social service in its own right. As the Gazette went to press, the next round of fights was on the calendar for May 15.