A rationalist’s surprising—especially to himself—spiritual awakening.

By Jerome D. Levin

If you told me in March 2003 that Buddhist prayer flags would be hanging in my backyard and that I would find them not only aesthetically pleasing but spiritually meaningful, I would have been not only incredulous but dismissive. A rationalist subscribing to such superstition? No way. But after 10 days of trekking in Bhutan’s Himalayas, plus several days visiting temples, monasteries, stupas, and dzongs (historic fortresses now used as monastic training schools), I not only look at my prayer flags with deep satisfaction; I meditate focused on thangkas (religious paintings), wear a protective red thread, and finger worry-beads made of wood of the Bodi tree (the same type of tree under which the Buddha achieved enlightenment). Bhutan was truly a transformative experience.

The trip started out incredibly pressured. There were reports, patients, students, and lectures, not to mention inoculations, medicines, equipment, and clothing to be procured. The stress of preparation was compounded by fears of SARS, terrorism, and the Iraq war. Should we cancel?—we being myself and my “niece,” Ariel, the daughter of my oldest friend from Penn undergraduate days, Debby Devine nee Goldberg CW’60. (Thirty-five years my junior, Ariel never made me feel inadequate or antiquated when she surged ahead. Beautiful, resourceful, delightfully intense, passionately open to new experience, she was the ideal traveling companion.) In the days leading up to the trip, Ariel’s mother alternated between near-hysteria and vicarious excitement. In the end, the latter won out and we departed with her, still-fearful, blessing.

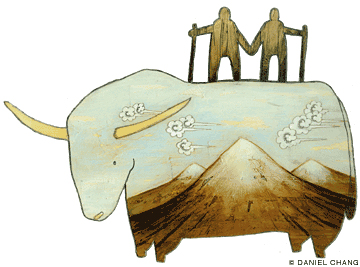

The majesty and grandeur of the Himalayas must be seen to be believed. The descent into Paro, location of Bhutan’s only airport, was magnificent. I felt as if I could reach out and touch the mountains. After clearing a rigorous SARS screening, we stepped out of immigration and met Palden, our wondrous guide—a magnificent expositor of his culture and of his country’s natural wonders, an opener of doors of all sorts, high-spirited, funny, knowledgeable, and highly protective. We always felt safe with Palden, and given some of the places and situations we would encounter—a hailstorm at 16,000 feet, a mad charging yak, and a second 16,000-foot pass with precipitous multi-thousand-foot drop-offs in deep snow—that was no small boon.

Palden drove us to the Gangtey Palace Hotel, which amazed us with its magnificent painted and carved wood, its frescos, and its stupendous views of distant snow-covered peaks. As the afternoon waned, we drove to an ancient Buddhist temple, where Palden cajoled the caretaker into opening its locked doors. Seeing the objects of veneration and religious wall paintings within, all lit by other-worldly diffused lighting, was deeply moving. When Palden prayed to Guru Rimpoche, the Tibetan saint who brought Buddhism to Bhutan, we joined him, genuinely sharing in his experience of the sacred. When the monk blessed us with holy water, we did feel blessed.

Om manni padme hum became our mantra. It all felt natural, organic, integrated, and right. Yet I was also aware of the superstitious side of the culture, and was amazed that the veneration of relics, worship of saints, monks pledged to celibacy, a view of life that holds that all is suffering and that non-attachment is the route to happiness, had such strong appeal for me. When I encounter their equivalents in the Christian West, they leave me cold. I think my reaction had much to do with the absence of coercion or of religious persecution by Buddhists. Buddha’s “middle path” has as its goal happiness and lacks the self-hating and life-denying characteristics of much Western asceticism.

Our second day we climbed 2,500 feet to the Tiger’s Nest monastery, which hangs on the edge of a 1,000-foot sheer cliff. This is magical architecture. The climb is exquisitely beautiful. Two thirds of the way up is a tea house, where we sat in the caressingly warm sun before finishing the ascent to contemplate the astonishing beauty emanating from the monastery’s integration of nature and art.

That afternoon, we visited Paro Dzong, which contained a monastic school for boys aged seven to 12, complete with a fearsome discipline master, whip and all. To our surprise, the second he left the room, the spitballs started flying, punches flew, and the scriptures went unattended.

The next day we started trekking, accompanied by eight horses, two mules, two horsemen, a cook, and his assistant. The horsemen sang folk tunes as they worked and walked. The head cook kept his distance as befit his high status. Up to 10,000 feet, cows were everywhere. Above 10,000 feet, yaks, not the most amiable of beasts, were the rule.

That first day was easy enough—a pleasant meander past fields and farmhouses, people coming out to greet us, the assistant cook humming along with a hot lunch on his back, cows and dogs everywhere—until we crossed a river and started climbing more steeply. By the time we arrived at camp, seven miles later, I was maxed. As the sun set, the horsemen rounded up their grazing charges and tethered them nearby lest they provide a meal for wolves or jackals.

The second day was a 13-mile continuous up-and-down challenge. Our camp that night—more than 11,000 feet up—was near a “communal hut,” a rough stone building with a fire pit used by nomadic herders. Yaks, rather like cats rubbing against the furniture, scratched themselves against our tents as we put on layer after layer against the cold.

On day three, as the sun climbed we stripped to shorts and t-shirts and headed for base camp at Jhomolhari, the sacred mountain. This was perhaps the most beautiful campsite I have known. The towering, snow-clad mountains; the romantic ruins of the dzong; the frayed prayer flags, becoming one with nature as they disintegrated; the yaks, the dogs, and the trail to Nyile La—the 16,000-foot pass we were to climb—all came together as if composed by a great painter.

The next morning, we started for Nyile La. The altitude made for a tough, slow climb. I had to stop every 20 yards to catch my breath. The top was loose scree and very steep. As I peaked, I was exuberant. Tears ran down my face. Ariel wept with joy and emotion. No sooner had we raised our hands—not in hubris, but in gratitude—than black clouds rolled in, followed by hail, thunder, and the sound of distant avalanches. There was no place to hide. The hailstones grew to golf-ball-sized. It was two hours before we walked out of the storm, and another three before we reached the tiny village of Lingzhi.

It rained that night, which meant it was snowing in the passes. We were between two 16,000-foot passes, with no other way out. I woke up several times that night, fearful of what sounded like continuous avalanches—actually the rushing river we were camped next to, as I saw in the morning.

During a rest day at Lingzhi, we explored the village and its cliff-top dzong. It was occupied by one monk, who admitted us to his meditation cell—where there was a poster, used as wallpaper, of a large-breasted nursing mother feeding her infant, inscribed in English, which he didn’t understand, “Breast feeding builds strong teeth.” Regardless of the incongruity of the picture, the room and the monk projected centeredness, calm strength, and serenity. While we explored the dzong, Palden went ahead to reconnoiter. Returning to camp, he reported that a herd of yaks had been driven over the pass and, fortunately for us, had trampled down the snow.

Still, it was an extraordinarily difficult climb. I had to stop every other step to catch my breath, but we persevered and reached the snow line. From there on there were precipitous drops at the edge of the narrow, slippery trail and precious little oxygen. When prayer flags greeted us at the top, I experienced an emotion hitherto unknown to me. A mixture of awe, gratitude, at-oneness and exhaustion, it stayed with me.

The last two days of the trek held ample challenges of their own. We followed a river whose towering cliffs on either bank were reminiscent of Sung landscape painting.

Our last day we were transversing a sharp rise on a narrow trail that fell precipitously to our right when an out-of-control, adolescent-male yak charged over the crest, hell bent on trampling us or tossing us down the precipice. At Palden’s frantic urging, we scrambled up the slope on our left. It was a close call. Moments later, two yak herders appeared, futilely in pursuit.

Finally, we came out on a lumber road, which ended in a village with a small general store. Far above, there was a monastery from which monks descended to buy Coke. A wondrous covered bridge, intricately carved, flying prayer flags in all stages of being, led to the monastery. We crossed to be treated to a show by dozens of langur monkeys. We had made it, and the monkeys were congratulating us.

The next morning we were driven to the capital, Thimphu. That night, we had a wonderful dinner with Palden’s family and the next day paid our last temple visit. A festival was in progress and children were being brought to be blessed. The lama came out and tied a protective red cord around our necks, poured holy water over our hands, and sent us on our return journey safeguarded from SARS and those aspects of Western culture that would attempt to undermine our serenity.

We drove back to Paro and in the morning, Palden took us to the airport. As we parted, he gave us gifts from his sister and then a gift from him—Buddhist prayer beads that he put around our wrists. The three of us wept; our sadness at leaving Bhutan was palpable and strong. Then Ariel and I strode toward customs and the West.

Epiphanies fade, yet I remain more open, more receptive, and more in contact with the mystery, the mutability, and the sacredness of all things.

Dr. Jerome D. Levin CGS’61 practices psychotherapy in Manhattan and Suffolk County, New York, and teaches at New School University. He has published 12 books on addiction, psychotherapy, and the self.