A “painfully cheerful” solar eclipse enthusiast is helping the country prepare for the singular astronomical event of 2024.

One day in 2012, Debra Ross C’91’s 11-year-old daughter, Ella, came home from an astronomy class at the Rochester Museum & Science Center with an announcement. “In five years, I’m going to be 16 and have my driver’s license, and you and I are going to go on a road trip to Missouri to see the total solar eclipse.”

“Sure!” Ross replied, though her inner monologue was skeptical. It gets dark every night. I know what a shadow is. What’s the big deal?

But Mom kept her word, and in late August 2017, Debra and Ella began the 800-mile drive from their home in Rochester, New York, to St. Louis. Ella had liked the city on a prior visit, and it was close to the path of totality, where the moon would completely cover the sun during the August 21 eclipse.

Their first stop was the Saint Louis Science Center. Deb served on the board of the Rochester Museum & Science Center, and she was the creator of Kids Out and About, a web platform that lists family-friendly activities in communities across North America. Whenever she traveled, she visited the local science museum.

At the gift shop she bought two of the last three mugs commemorating the Great American Eclipse. She told the clerk she was from Rochester, which would experience its own total eclipse for three-and-a-half minutes on April 8, 2024. He leaned forward, conspiratorially. “Whatever merch you’re thinking about buying, double it,” he said. The town was buzzing with tourists, and several large events were planned downtown. Ross started to realize that the eclipse was a very big deal.

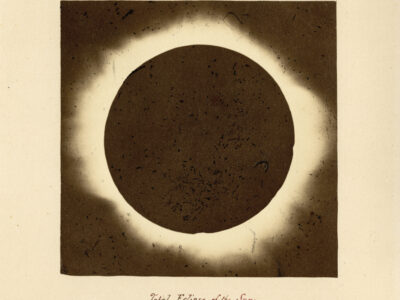

The next day, the Rosses drove 24 miles southwest to the hamlet of Kimmswick, inside the path of totality, and parked in a clearing. At 11:49 a.m., as the women watched through safety glasses, the moon began to creep across the sun’s face. At 1:17 p.m., the sun suddenly disappeared, and the Rosses stood fully in the moon’s shadow. The temperature dropped, taking the edge off the summer heat. Crickets began to chirp. A red-and-gold sunset glow lit the horizon in all directions. Mother and daughter removed their glasses to look at the sun’s corona, the outer atmospheric layer that’s ordinarily impossible to observe amid the brightness of the sun itself.

“My life was transformed during those minutes of totality,” Deb says. “I was aware of four bodies in the entire universe: the sun, the moon, the earth, and me. You can read about celestial mechanics; you can watch Neil deGrasse Tyson; you can look through a telescope; but you feel the celestial mechanics with your body during an eclipse. You’re not just looking at something, you’re in something.”

Gazing upward, Ella felt a swelling sense of calm and accomplishment. It was partly personal pride: she had completed the trip she had envisioned five years earlier. But it was also gratitude for the astronomers and mathematicians who had come before. “It makes me feel so happy about the time I live in, and the level of knowledge I have, because of what humanity has been able to figure out,” she says.

The two reveled in the darkness for two minutes and 19 seconds, until the moon began to slip away from the sun and the eclipse drew toward its end.

“Then my mom and I headed home,” Ella says. “And she went insane.”

As they drove back to Rochester, Deb could think of only one thing: how she needed to help people prepare for April 8, 2024, so that every resident and visitor would have the best possible eclipse experience. That goal would dominate the next seven years of her life.

Ross serves as chair of the 750-member Rochester eclipse task force, and in 2019 she took on an even larger role as the cochair of the American Astronomical Society’s solar eclipse task force. That group helps cities in the 2024 path of totality—which stretches from Texas to Maine and encompasses 31 million people—prepare for extraordinary crowds seeking the dramatic experience of midday darkness.

Neither astrophysicist nor astronomer, “I’m just a painfully cheerful person, and I do nothing half-assed,” Ross says. “If anyone has to get hundreds of people to work together for zero money for several years for something that happens for three minutes and 38 seconds, it has to be a painfully cheerful dork.”

Ross wasn’t always so outgoing. In fact, her high school classmates in Cranford, New Jersey, informally declared her “least likely to become a professional cheerleader.” Ross sat quietly at the back of the classroom and graduated as valedictorian. As an English major at Penn, she continued to work hard to make good grades, but she noticed that many of her fellow students seemed “much bolder about stepping out of their comfort zone.” Inspired, she realized that she too could create her own definition of success.

Historian Alan Charles Kors—Penn’s Henry Charles Lea Professor Emeritus—also nudged her in this direction. “He wanted to help you learn how to think, not tell you what to think,” Ross remembers. “I realized that the distance between a B-minus and an A in his class was the same thing as the distance between a B-minus life and an A life. It was thinking for yourself.”

After graduation she worked for a small publisher in New York, implementing an enterprise management system to shift the company from paper to computers. Ross discovered an affinity for the work and went on to establish a technology consulting business. As a new parent in the early 2000s, she launched Kids Out and About, a constantly updated web calendar of activities for children and families. In 2009, she turned the site from a community service into a business and expanded it across the country.

By the time she saw her first eclipse in 2017, she knew “everybody” in Rochester. She also was the incoming chair of Visit Rochester’s travel industry council and began every meeting with a reminder about the 2024 eclipse and the up to 500,000 visitors expected to descend on the city. Ross assembled a local task force, including representatives from education, business, public safety, and tourism, to prepare. She made sure the organizations planning events—the science museum, the Rochester Philharmonic, the Minor League Baseball team—were coordinating.

She also began attending meetings of the American Astronomical Society’s solar eclipse task force, which organized to share best practices from 2017 with cities in the 2024 path of totality. By the time the AAS sought a new cochair for the task force, Ross had impressed the group of astronomers with her energy, efficacy, and, yes, her painful cheerfulness.

“We decided that she would be perfect because she knew the community, she had the enthusiasm, she got things done, and she was a great motivator of people,” says Rick Fienberg, a professional astronomer and the AAS task force’s project manager. “She became critical to the whole endeavor and has proven to be exactly what we hoped for, which was a dynamic, involved cochair.”

As she helps other communities learn from highly prepared cities like Rochester, Ross still doesn’t know where she’ll view the eclipse on April 8. She may need to be on call for the city of Rochester. She might end up on national television.

Wherever she lands, she’ll consider the eclipse her legacy for Rochester and for the country. “It’s a singular, unequivocally positive moment in the 21st century,” she says. “I can point to that and know I helped make this amazing experience even better for millions of people.”

—Robyn Ross

Writer Robyn Ross is not related to Deb and Ella Ross.