Class of ’90 | Fourteen months ago, astronaut Garrett Reisman EAS’90 W’90 launched from Earth on the space shuttle Endeavour, bound for a three-month stay on the International Space Station (ISS). But by the end of the first month, he and a fellow crewmate found themselves chafing under station commander Peggy Whitson’s tyrannical rule. So they decided to mutiny.

Armed with inflatable pirate cutlasses they had smuggled aboard, the conspirators “tied Peggy up,” Reisman recounted recently. “We threatened to make her walk the plank out of the airlock, and we called down to Mission Control” with a list of non-negotiable demands. First, they were tired of flying east, and wanted to turn around and fly west. Second, they wanted a hot tub. Third, pizza.

Unfortunately the ground crew realized it was April 1st, so the mutineers received none of their demands. But Reisman did score a small personal victory. “For five minutes,” he said, “I did get Mission Control to address me as Commander Reisman.”

A compact, energetic man who left Penn in 1990 as a graduate of the Jerome Fisher Program in Management and Technology [“Alumni Profiles,” Sept|Oct 1998], Reisman returned to campus this past February in a fitted blue flight suit emblazoned with the NASA logo to talk about his three months living in space. His talk was part of the Technology, Business, and Government series hosted by Penn Engineering.

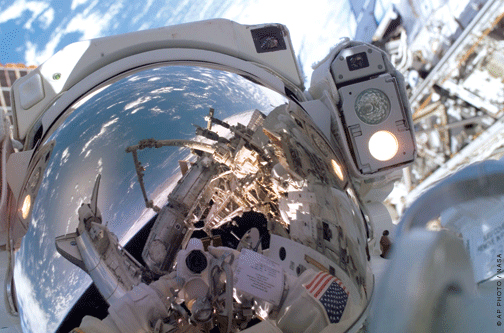

In Reisman’s official NASA crew photo, the men of STS-123 stand in two neat rows, carefully posed in their bulky, orange spacesuits. “As you can tell, we’re all very serious astronauts,” he said—then showed an unofficial photo taken a moment later, showing the same seven men after they had spontaneously tackled their mission commander, forming a pile of bodies.

“We call this ‘one giant heap of mankind,’” he added.

Reisman’s easy smile almost concealed the scope of his achievements. When he arrived on the ISS, he took over the job of flight engineer from Léopold Eyharts—no easy task, he acknowledged, given that “Leo is a general in the French Air Force.”

But Reisman’s good humor was actually one of the qualifications that, along with his intellectual firepower, helped him get into space. When NASA makes the final cut for mission personnel, he explained, the question they’re trying to answer is simply, “Would you like to go camping with this person for six months?” In such close quarters, a personality conflict is just as dangerous as equipment failure, and an easygoing nature can be a crucial piece of the jigsaw puzzle that forms a successful crew.

Reisman showed his quick wit during a televised interview with Comedy Central’s Colbert Report last May—live from the ISS, patched through Mission Control in Houston. When host Stephen Colbert cited him as a true member of the “Colbert Nation,” Reisman corrected him: “‘Colbert Universe’ would be more appropriate.’” (His host’s delighted response: “We’ve gone galactic!”) And when Colbert suggested that “it looks as though you can literally do a flip from laughter up there,” Reisman came through with a laughter-induced, slow-motion back-flip. The studio audience went wild.

But Reisman offered reminders that spaceflight isn’t all high-altitude high jinks. During his stay the station was still being constructed at a furious pace, so not only was the crew responsible for an array of science projects, but cargo ships were arriving and departing every 10 days. Like a moving crew, they had to unpack each ship and take on equipment, new clothes, food, water, and air. (“We really liked to get the oxygen,” he said dryly. “That was very nice.”) Then they’d shoot the station’s trash and waste back into the atmosphere to disintegrate.

The fact that human spaceflight is still a new and dangerous project was evident when he told of the “very interesting ride home” by three of his colleagues. Though their Russian-built Soyuz capsule left the station without a hitch, just before they reached the Earth’s atmosphere, a single pyrotechnic bolt failed to fire, leaving their reentry capsule glued to a module that should have been jettisoned. Instead of hitting the atmosphere heat-shield forward, they came in backwards, caught in a violent spin. The hatch was forced to absorb a blistering heat it was never designed for, and it began filling the cabin with smoke. Eventually the bolt gave way under the huge stress; the capsule righted itself; and the crew members landed unharmed, if a tad unhinged.

“Fortunately, Russians tend to make things really beefy,” Reisman said.

Reisman brought a couple of mementos from the University on his space odyssey. One was a Penn pennant that flew from the wall of the space station during his stay. He presented it as a gift to the engineering school, noting that it looked none the worse for wear despite having traveled about 40 million miles.

He also brought a knob and a plate from the 30-ton grandfather of all computers, the ENIAC—originally built at Penn’s Moore School in 1946. Reisman attached the knob to the center of the Endeavour’s control panel as a tribute, and in the photo it looks surprisingly at home in the sea of cockpit instrumentation.

Reisman’s slide show concluded with a couple of views of the Earth from space, shots he took by pointing a 55-mm camera out the window.

“This is what it really looks like,” he said, staring up at the hugely magnified projection, his face half-shadowed in the dim auditorium light. In his photo clouds are stretched over the horizon like textured skeins of cotton, curving toward an orange fringe where dusk is advancing over the Earth’s surface.

“We’re used to thinking of dusk and dawn in intervals of time,” he said. The view from 190 miles up has altered his perspective. What he sees now is a “shadowy band separating day from night” that’s “slowly marching across the planet.” When the station’s orbit passes over the dark half of the planet, the Earth seems to disappear.

“The good news is that when you come out the other side, the Earth always shows up again,” he said with a laugh. “So it’s very reassuring.”

—Sean Whiteman C’11