From swinging standards to avant garde nonconformism, Penn music professor, jazz drummer, and shapeshifting composer Tyshawn Sorey has won acclaim for “awesomely confounding” music whose “vulnerable virtuosity” can “open different portals in your depth of feeling and imagination.”

By Nate Chinen | Photography by Nathan Bajar

The midcourt line of a high school gymnasium probably isn’t the first place you’d go looking for a heralded composer’s world premiere. But late last spring, it formed the epicenter of an absorbing new work by Tyshawn Sorey: Be Holding, a site-specific piece designed for the century-old Armory at North Philadelphia’s Girard College.

Dusk was descending, a blue-black filtering through the Armory windows, as lead performers David Gaines and Yolanda Wisher came to a pivotal point in the libretto—a book-length poem by Ross Gay, also titled Be Holding, that builds a rhapsody out of Julius Erving’s iconic reverse layup in the 1980 NBA Finals. “What’s my study?” Gaines recited, a touch of urgency in his voice. “What’s my practice? What are we trading in? What are we looking at? My arms now cutting circles in the air.”

At that cue, five Girard College high school students joined Gaines and Wisher in coordinated movement—darting back and forth, sneakers chirping on the parquet floor, as they each crooked an arm above their heads. Then, a sonic boom: the furious wallop of a bass drum, timpani, and bongos from the new-music quartet Yarn/Wire. Up to this point, Be Holding’s musical score had been all about shifting resonance and eerie dissonance, a subtle backdrop for the lyrical flights of the poem. So the cacophony startled like a jump scare in a horror film, thundering mightily within the cavernous dimensions of the gym.

Be Holding emerged from a multiyear collaboration between Gay and Yarn/Wire along with director Brooke O’Harra, who has been on Penn’s Theatre Arts faculty since 2016, and Sorey, who came to Penn in 2020 as a Presidential Assistant Professor of Music. Gay, speaking courtside, marveled at how the artists had all inhabited and enlarged his poem over time. “There were these moments of stillness and quiet in the beginning of the process, as they were learning how each other work,” he said, recalling some early rehearsals. “And I was like, ‘Oh, that’s how you learn how to think together—in this kind of silence.’ And that was really moving to me. That was beautiful.”

The heart of that stillness was Sorey, who embodied the same quality during the premiere—bearing silent witness in his trademark black hoodie from a folding chair beside the bleachers. O’Harra, reflecting on the alchemy of their work together, later mused: “It wasn’t until I was sitting with him watching the show that I could fully see what he made, in a way.” Watching Sorey watch Be Holding, it was possible to visualize that absolute faith in an emerging picture, along with the quiet intensity of his listening.

As the raucous explosion in the piece subsided, giving way to a shimmer of overtones—a brush of mallets on a vibraphone, blending with a barely struck gong—Gaines reached a passage in Gay’s poem that hails “the black pull of genius.” The line jumped out as a fitting encomium for Sorey, who has been honored with a MacArthur Fellowship (commonly known as the “Genius Grant”) as well as a United States Artists Fellowship and a slate of prestigious commissions. His music has been praised as “awesomely confounding” by the august New Yorker classical critic Alex Ross, partly because of its refusal to conform to expectation or category.

That last part is important, because even as Sorey, at 43, has ascended to an exalted tier of prominence among new music composers, he’s also solidified his stature as one of the most thrilling drummer-bandleaders in jazz. And for the last few years, he’s been just as busy outside of public view, shaping a culture in Penn’s music department that aspires to the same voracious, capacious imagination found in all of his work.

Sorey lives with his wife Amanda Scherbenske, an ethnomusicologist who also lectures at Penn, and their two young daughters on the Philadelphia Main Line, a short drive from campus. The week before Be Holding, we met at a Havertown coffee shop where he often camps out to compose. The imposing figure that Sorey cuts onstage—a mountain of a man, clad head-to-toe in black, brow furrowed in monastic concentration—softens considerably in person. He’s gregarious, thoughtful, and approachable, not one to give off airs. (On this day, his phone pinged with news of a hassle on the home front: a busted appliance had led to a minor plumbing emergency.)

At one point in our conversation, I half-apologetically raised the subject of musical taxonomy—all those genre terms he’s taken pains to shrug off or ignore. “What the music is depends on who the listener is,” he said, with a certain equanimity. “For me, I’m a listener who’s curious not only about the music that I’m playing, but all music in general. So terms like jazz—or even terms like improvisation—carry so much historical baggage and negative connotations that I feel shouldn’t align with what I’m doing.”

Sorey was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1980, just as the crack epidemic was beginning to exact its brutal toll on the city. His parents separated when he was three, and he spent some of his childhood in a housing project. His musical education came where he could find it: on the weathered piano at his grandmother’s Catholic church; over the FM dial, via public radio stations WKCR and WBGO; in the elementary school band, where he played the trombone. But percussion was always in the picture: he clattered on pots and pans until his grandfather scraped up enough to buy him a drum set, around age 12.

At Newark Arts High, and later William Paterson University, Sorey immersed himself in the jazz tradition—meaning not only the work of canonical modernists like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis but also avant-garde mavericks like the pianist Cecil Taylor and multireedist and composer Anthony Braxton. He also delved into the work of 20th century classical modernists like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Morton Feldman. And he began to circulate on the scene in New York, most visibly with the pianist and composer Vijay Iyer. This was the context in which I first encountered Sorey more than 20 years ago, playing drums in Iyer’s trio at the Greenwich Village jazz club Sweet Rhythm.

“He was still a kid,” recalled Iyer—a MacArthur “genius” himself, lauded recording artist, and now a tenured faculty member at Harvard—of those early gigs with Sorey. “I remember [pianist] Michele Rosewoman saying at the time, ‘Tyshawn is still just figuring out how to be.’ I think we all are, around that time in our lives. But he was already, I knew, one of the greatest artists I would ever know: one of the greatest musical minds, and one of the greatest performers of all time. I just felt like I could do anything with him, that he could do anything, and that whatever we did together, he would always make it shine.”

Sorey went on to distinguish himself in groups led not only by Iyer, but also the saxophonists Steve Coleman and Steve Lehman—as well as Fieldwork, a collective trio with Lehman and Iyer featuring music by all three members. Even in a jazz era full of dazzling drummers, Sorey stood out for the acuity of his playing: his ability to combine multiple pulses in a sort of vortex; the rare power and velocity at his disposal, handled so casually as to seem an afterthought; and his way of reconciling fiery abandon with a careful, almost dainty attunement to texture and tone.

His own recent output has engaged in earnest with the jazz idiom, notably on a surprising pair of albums released in 2022: Mesmerism, a gemlike studio release by an acoustic piano trio; and The Off–Off Broadway Guide to Synergism, an ecstatic three-disc testament of a quartet residency at The Jazz Gallery in New York, with a distinguished elder, Greg Osby, on alto saxophone. Both albums feature the virtuoso pianist Aaron Diehl, who has a reputation as a fastidious steward of jazz and classical traditions. Sorey, who had never played with Diehl before the recording session for Mesmerism, found an instant affinity rooted in their mutual commitment to precision and aversion to stereotype. “He’s like a brother to me, basically,” Sorey said.

His recent turn toward songbook standards in a swinging time feel would hardly seem revolutionary, if not for the precedent that Sorey set with his work. He recalls writing his own combo music in the mid-2000s and realizing that it sounded a lot like the rhythmically assertive, harmonically restive music he’d been playing with Lehman and Iyer. That hint of mind-meld was affirming but also limiting, Sorey felt. “I wanted to do something that was completely different,” he said, recalling the desire to establish his own signature as a composer and bandleader. The result, beginning with his 2007 album That/Not and extending to Oblique-I and others, was a style that put combustible action and watchful quiet on a conceptually equal footing.

“It’s this state of consciousness that you enter where anything that happens is allowed,” Sorey explained. “And anything that happens is full of intent, and integrity, and full of, um, chutzpah.” He laughed at his choice of words, then quickly added: “Like, it’s all there, no matter whether you’re playing a single note for four minutes, or you’re playing a bunch of notes. It’s really the intent that 100 percent has to be there.”

Sorey intensified this conviction during his studies at Wesleyan, where he earned a master’s in music composition and was mentored by Anthony Braxton. He then studied composition under trombonist, composer, and electronic music pioneer George Lewis at Columbia University, earning a doctor of musical arts degree. Both Braxton and Lewis are members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, an organization committed to sustaining new original work independent of market considerations or presumptions of style. (Lewis’ 2008 book A Power Stronger Than Itself: The A.A.C.M. and Experimental Music is an essential resource.)

At Columbia, Sorey ran up against a prevailing culture of academic composition. As in many ivory tower music departments—including Penn’s, in a previous era—there was a tradition of venerating grand theoreticians who create the music but would prefer not to get their hands dirty playing it. For Sorey, who was onstage with Iyer at The Village Vanguard the night before defending his doctoral dissertation, this seemed exactly backwards.

“I’m happy to be part of a generation that is turning that around,” Sorey said, “and part of an institutional model that does away with that kind of old-school thinking—where a performer’s not a real composer, and a composer shouldn’t necessarily subject themselves to performing. We’re far removed from that now, and I thank people like George Lewis and Anthony Braxton for setting a precedent for this model.”

That precedent also entails a refusal to be painted into a genre corner—something Sorey has internalized completely. He recalls that when he first began working with the International Contemporary Ensemble, known as ICE, “I told them that I want to make music from a space where none of these genre names or divisions related to compositional performance existed in the first place.”

Flutist Claire Chase, the founding artistic director of ICE and one of the most galvanic figures in new music, maintains a collaboration with Sorey. “He’s such an important community builder,” she said after one of their concerts in New York. “I see him as this glue for so many different musical movements and energies that are afoot right now. And it is because he is wildly open-minded. That’s a very, very unusual quality for any composer to have, especially now. We’re so siloed and can become so blinded by our aesthetics and histories and successes. But Tyshawn has the most voracious musical appetite of any musician that I know. He is constantly listening to other people’s music.”

Sorey has channeled this openness back into his work, notably through a series of dedications that function as personal offerings. “For George Lewis,” a nearly hour-long piece that he recently composed for the ensemble Alarm Will Sound, captures a quality of patient permutation that marks Lewis’ own work. (“Bells toll in the piano as winds and strings stretch their notes to breathtaking lengths,” wrote NPR classical critic Tom Huizenga, describing the piece, “while chromatic chords twinkle like stars in the firmament.”) Sorey has created a series of other pieces with meaningful dedications, like “For Fred Lerdahl,” after the composer who served as his principal advisor at Columbia, and “For Arthur Jafa,” after the pioneering Black cinematographer and video artist.

These gestures stem from Sorey’s insistence on rooting his work in genuine emotion. “If there’s no emotional import there for me, I have to change it so that I can have some kind of feeling,” he said. “And it took many years of doing that to arrive at a place where I could touch on these inner feelings that I may have, be they related to politics or be they related to people who have had a tremendous influence on me.”

Hence the dedications, he added. “Or it could be for somebody I’m mourning, or wish I’d had more of a collaborative relationship with. I think that that’s especially inherent in the piece ‘For Jaimie Branch,’ because the two of us talked for quite some time about doing some sort of collaboration together.”

Branch, a brashly original trumpeter who straddled the new music and improv realms, died in 2022, at 39. The shock of her death led Sorey to compose a work in her honor. “It was like, ‘How do I convey this feeling that I get from listening to her music, but in a way that does not sound like her music?” he said. It’s precisely the sort of puzzle that would seem to suit Sorey, who once named an album Koan, and seeks meaning in a play of irresolution and implication that many others might brush aside.

“For Jaimie Branch” was a co-commission of TAK Ensemble, an experimental chamber quintet, and the New York Philharmonic, which presented its world premiere last December. TAK Ensemble spent 2022 as a Visiting Ensemble in Residence at Penn, and it was there, crowded into an upstairs classroom in Fisher-Bennett Hall, that the group held its final rehearsals of the piece.

Sorey occupied a chair near the door, while the ensemble members sat in a circle, making notes to his score on their iPads. TAK Ensemble had commissioned a previous piece by Sorey, “Ornations,” whose brisk formal convolutions and technical demands posed a formidable challenge. Jaimie Branch had been a friend to several of the group’s members, charging this new work with a different sort of difficulty.

But it was also clear, as the musicians worked through the piece, that “For Jaimie Branch” required immense proficiency and focus of its performers. Sorey set the piece at a glacial tempo, with soft expressions that often require an instrumentalist to sustain a timbre at the edge of their comfortable threshold.

Sorey, listening intently to the ensemble’s efforts, suggested the occasional alteration, like a tailor fitting a bespoke garment with a client. He offered to have soprano Charlotte Mundy move one note down an octave, for instance, if she couldn’t find the right sonority in her higher register. (She declined, resolving to preserve the integrity of the original idea.) Elsewhere in the piece, there’s a split tone on clarinet, achieved using multiphonic techniques and held for several long seconds.

“Is that hard to achieve at that dynamic?” Sorey asked the group’s clarinetist, Madison Greenstone, after hearing them struggle slightly with the part.

“It’s not,” Greenstone answered, sounding determined. “I mean, it is, but it’s not.”

Marina Kifferstein, TAK Ensemble’s violinist, later described another issue: “The pulse is so slow, it’s kind of like syncing our heart rates,” she said. “Being able to feel that extremely slow pulse together is very challenging and requires a tremendous amount of focus—which kind of speaks to the intention of the piece.”

Rehearsal ended with the first full run-through of “For Jaimie Branch”—and over the course of 18 minutes, TAK Ensemble fully embodied that ruminative intention. Like many of Sorey’s signature works, the piece involves a deep engagement with silence, and with a shifting of timbres as gradual as the lengthening of a shadow along a wall. Different members of the group took turns sustaining long tones, sometimes in a pinpoint dissonance and sometimes in what felt like a prayerful attunement.

Remarkably, for a work so suffused with abstract gestures, the piece left an extraordinarily vivid emotional impression. After the final bar, the musicians seemed almost stunned, reluctant to let the moment pass. After a few seconds of weighted silence, Sorey cleared the air with a joke: “All we’re gonna do is mess it up Saturday,” he said, referring to the premiere. Amid relieved laughter, he quickly added: “Great work. Thank you so, so much. Great rehearsal today, and … wow.” Moments later, he encased flutist Laura Cocks in a bear hug as they buried their face in his chest and wept, overcome by the grief made manifest in the music.

“I think that the most virtuosic thing that anybody can do, whether it’s in music or interpersonal relations, is to be vulnerable,” Cocks later reflected. “It takes concerted effort, and a lot of care. And I think Tyshawn’s music—especially what he’s been crafting over the last several years—really speaks to that kind of vulnerable virtuosity, and a very mature virtuosity. It’s such a privilege to play; I feel like to engage with it makes me a better person. It’s the kind of virtuosity that I hope we all aspire to.”

For Sorey, this mode of working is not just an antidote to the clinical nature of so much composition in the academy; it’s a way of anchoring himself in the world. “Whenever I’m working on music, I just have a tendency to tap into something that’s reflective,” he said. “I tend to have that feeling about a lot of things that I experience in life, and that I read about. So how do I write music that is reflective of these inner emotions, and these other feelings that maybe we don’t tend to engage with? It’s like: how do I get to that?”

The most ambitious manifestation of Sorey’s drive toward these unanswerable questions, at least up to this point, is Monochromatic Light (Afterlife), which he presented in two versions last year. Originally commissioned by the Rothko Chapel in Houston, along with the Houston performing arts organization DACAMERA, the piece evolved into a multimedia opus by the time it reached New York’s Park Avenue Armory last fall. In addition to Sorey’s haunting score, it grew to include abstract visual art on a monumental scale by the prominent painter Julie Mehretu, and a corps of contemporary “flex” dancers choreographed by Reggie “Regg Roc” Gray.

This ambitious, immersive staging had been designed in collaboration with legendary director Peter Sellars, who told me during rehearsals: “Every time I’ve heard Tyshawn’s piece—and I’ve heard it a few thousand times in the last eight months—I hear a different piece. I mean, Tyshawn’s music just constantly reaches you in different ways, and opens different portals in your depth of feeling and imagination and historical consciousness.”

Monochromatic Light (Afterlife) began as a double response of sorts: a tribute to the painter Mark Rothko’s abstract canvases made for the Rothko Chapel, and also a nod to Morton Feldman, who premiered his “Rothko Chapel” at the dedication in 1971. As a deep admirer of Feldman’s, Sorey embraced the challenge—choosing a similar instrumentation of viola, percussion, and chorus, though with piano in place of celesta. The commission happened to coincide with the coronavirus pandemic, and a summer of protest after the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among others. Sorey found himself reaching for another layer of resonance; he swapped out Feldman’s soprano part for a bass-baritone, specifically the dynamic young singer Davóne Tines. “I’m thinking of our past history,” Sorey explained, “in terms of Black trauma and Black grief, having experienced centuries of this kind of violence towards us.”

At the Park Avenue Armory, where Monochromatic Light (Afterlife) sprawled to some 90 minutes, more than twice the length of its Houston premiere, Sorey was making tweaks to his score up to a day or two before opening night. This seemed to unnerve some of the members of the Choir of Trinity Wall Street, though the other musicians—violist Kim Kashkashian, percussionist Steve Schick, and pianist Sarah Rothenberg, all elite musicians in their field—took it more in stride. Like Tines, they were committed to channeling Sorey’s personal truth through the work.

“It is just staggering, what he holds inside of him,” marveled Rothenberg, who not only played the piano part in Monochromatic Light (Afterlife) but also commissioned it as the artistic director of DACAMERA. The piece joins a series of recent works by Sorey that reflect on the Black American experience—along with Perle Noire, an oratorio he wrote about the entertainer Josephine Baker, set to verse by the poet Claudia Rankine; and Cycles of My Being, a song cycle with lyrics by poet Terrance Hayes. (Both pieces, which respectively feature the soprano Julia Bullock and the tenor Lawrence Brownlee, were met with considerable acclaim.)

“Doing the performances over and over,” Rothenberg said of Monochromatic Light (Afterlife), “I was struck by the idea that there was so much pain and intensity in the piece, but no anger or aggression. Tyshawn is a very special musician in terms of how deeply he lives inside music. His pieces are a kind of environment that one lives in.” That immersive quality, along with the way it encourages introspection, imbued the piece with a shimmering emotional power. It wound up as a finalist for the 2023 Pulitzer Prize in Music.

It’s important not to lose sight of the fact that Sorey’s forthrightness with feeling is braided with the highest degree of musical rigor—a quality whose meaning can change according to the context. Chase, the flutist, provided a perfect illustration when she mentioned “Bertha’s Lair,” a piece she commissioned Sorey to write in 2016, as a duet for percussion and contrabass flute. I witnessed a performance of this piece at the Ojai Music Festival in California not long after its creation; as written, it’s a difficult, dynamic work.

“It’s gorgeous flute writing,” Chase said. But during a recent performance in New York, she added: “Just as we were walking out on stage, he said, ‘Forget the ink entirely. This is the piece. This piece now is just the two of us onstage together.’” Only the most supremely assured musician would be prepared to handle such a sudden shift, but Sorey knew that Chase would embrace the risk—along with the discipline of spontaneous composition that tends to more often get filed under “jazz.” She belongs to the growing contingent of classically trained musicians eager to work with these parameters. Regarding her overall rapport with Sorey, she enthused: “We meet in a space that is unknown to both of us until that very moment.”

Teaching, for Sorey, is a natural extension of his musical practice. Some of his early experience as an educator came more than a decade ago at the Banff International Workshop in Jazz and Creative Music, a summer program that Iyer led as artistic director. “I’d bring him every year,” Iyer recalled. “Every participant came to worship him, because he gave them so much, and because he really heard them as who they were.”

Iyer, who eventually got Sorey appointed as Banff’s co-artistic director, elaborated: “Tyshawn has unbelievable ears, so he hears the truth about everyone and everything. It can be almost a curse, but it becomes a blessing to everyone around him. Because of that, as an educator he’s unbelievably present for people, in a way that shakes them. He hears the truth in you that you haven’t yet heard. So that’s been beautiful to witness, too—to see him become the teacher that he is.”

Since his appointment at Penn in 2020, Sorey notes with satisfaction that the music department has seen “an influx of students who are interested not only in composition as such but also so-called improvisation—you know, spontaneous composition and that sort of thing.” He has mentored a cohort of graduate composition students, including the cellist Erin Busch Gr’28 and the electronic musician James Díaz Gr’28. But he also works with undergraduates both in and out of the music department, in a manner that recalls the example of one of his heroes, the late composer, pianist, and Penn professor James Primosch G’80 [“Obituaries,” Jul|Aug 2021].

“I have a very unorthodox way of teaching music theory where I have the students pick up any instrument that they have—even if it’s an instrument that has collected dust for a few years—and get familiar with these concepts,” Sorey said. “Because when you teach music theory, you’re teaching these abstract concepts related to tonal harmony. But when you get students directly engaging with the materials, with an instrument or with their voice, they realize that this stuff takes time to get under their fingers.”

Not everyone appreciates this hands-on approach, he allowed. “But those same people who took my theory course, three of them have returned to take my Intro to Popular Music course. I just finished teaching it this semester, talking about Black popular music. And it was a great experience, because then they were able to use their knowledge that they got from music theory and they’re able to create their own composition based on things that we talked about in this popular music world.”

The interaction of abstract concepts with tactile expression resurfaced clearly during performances of Be Holding, the multimedia piece at Girard College. Sorey presided over its staging during a typical whirlwind of activity for him: just before the premiere, he was in New York at the Long Play Festival, performing a Morton Feldman piece with pianist Conrad Tao.

He also had a new double album out: Continuing, a sequel to Mesmerism. It features just four songs, one on each side of an LP, composed by jazz titans like Wayne Shorter and Ahmad Jamal. Among the most “conventional” of Sorey’s albums, it reflects a new sense of freedom. “I don’t have anything to prove anymore,” he said. “And because my phone is not ringing from other musicians to play standards, why not make an opportunity where I not only do that, but also do it in a way that keeps me guessing?”

The week after Be Holding, Sorey took part in a residency of a different sort—with Iyer and Lehman, in a reunion of Fieldwork. The group, which hadn’t performed a proper engagement in a dozen years, settled in for three nights at Solar Myth, a new Philadelphia venue on South Broad Street, at the invitation of the presenting organization Ars Nova Workshop.

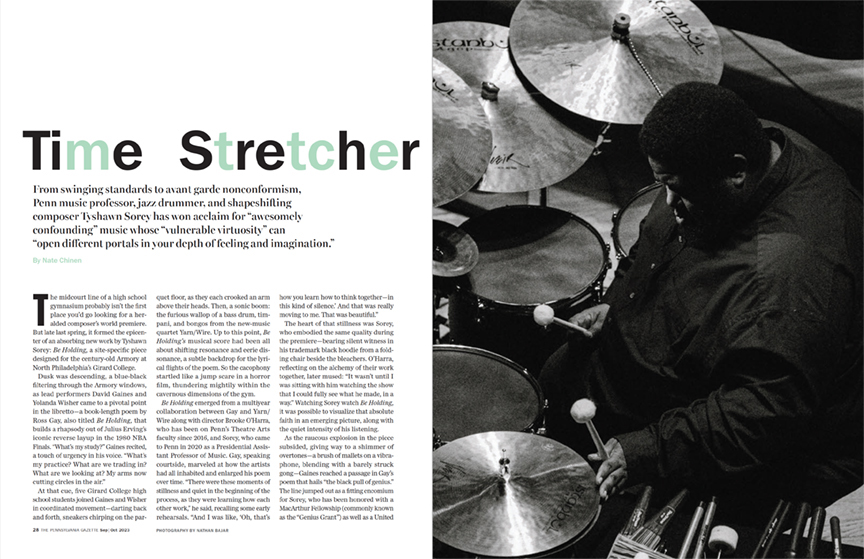

On the second night of the run, the room was packed solid as the members of the trio committed to a combustible yet selfless form of synergy. The music was a whorl of kinetic fury and dramatic incident, along with complex cyclical patterns that often rendered a melody in Cubist form. Each player shaped the sound, but Sorey had the most colorful expressive range: rubbing an open palm across the surface of his snare to create a frictive shudder; thrashing at his cymbals with both hands, his wrists like pistons. No matter how much of a rhythmic maelstrom he made, there was stoicism in his posture behind the drum set, as if he was engaged in a form of meditation.

The intensity of his physical outpouring in Fieldwork registered as something quite different from the power of his writing for Be Holding. That’s part of what makes him such a compelling figure, and why it’s worth remembering another creative truth he holds as self-evident. “To me it’s as if no work is ever finished,” he said. “You know, nothing can be played the same way twice, really, no matter how hard you try. The sound is not going to translate to the listener in the same kind of way.”

Whatever other considerations enter the making of a work, that last part is key. “It’s not about simply connecting the dots,” he said. “It’s really: How is this taking care of the listener? How is this going to transform the listener?”

Nate Chinen C’97 is the editorial director at WRTI, a contributor to NPR, and a music critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times,JazzTimes, Pitchfork, and the Village Voice. He is the author of Playing Changes: Jazz for the New Century and co-author of Myself Among Others: A Life in Music, the autobiography of impresario and producer George Wein. He writes a Substack newsletter on music and culture, The Gig.