To her mother, alumna Alice Paul was a “mild-mannered girl”; another observer compared her demeanor to “the quiet of a spinning top.” Her leadership in the fight to get US women the vote was a remarkable mix of unyielding commitment and savvy politics.

BY DENNIS DRABELLE | Illustration by Anna Heigh

When, on the sixth day of his presidency, Donald Trump W’68 noticed a banner with the message “RESIST” waving in the sky above the White House, he probably failed to recognize the tactic as one invented by a fellow Penn graduate. The irony was also lost, one assumes, on the Greenpeace activists who had scaled a nearby construction crane and unfurled the banner.

But the record is clear. It was Alice Paul G1907 Gr1912—best known for leading the campaign to give women the vote that culminated in the 19th Amendment to the Constitution—who first saw the White House for what it is. Not just the president’s domicile but also, in the words of Paul’s biographer Mary Walton, “a political nerve center.” Anyone who has ever picketed the White House, kept vigil there, or benefited from the protests of those who did, is indebted to Paul, a soft-spoken activist who ranks among the 20th century’s canniest political strategists.

The Pauls were Quakers to the core: born in 1885, Alice belonged to the eighth generation of Friends descended from Philip Paul, who had emigrated from England 200 years earlier. Based in Moorestown, New Jersey, the family adhered to the faith’s Hicksite branch, which put more emphasis on plain living than did the orthodox mainstream. Alice’s maternal grandfather had been a founder of Swarthmore, a Quaker college. Her father, William Paul, was a man of many parts—farmer, merchant, real estate mogul, banker—but his death when Alice was 17 seems to have left her relatively unscathed: “I was too young for it to be much of a blow,” she recalled.

Alice was attending Swarthmore at the time—a good student, fun-loving but noted for her dark, soulful eyes and precocious serenity. After graduating in 1905, she accepted a scholarship to a work-study program at a New York City settlement house. Although Paul concluded that municipal governments outperformed settlement houses in familiarizing immigrants with American ways, the experience gave her a taste of political activism. In 1906 she moved to Philadelphia and enrolled in graduate school at Penn. A year later she came away with a master’s degree in sociology. In her old age, she spoke of the “great joy” of taking courses at the University.

Another scholarship took Paul to a Quaker study center in Birmingham, England. She soon fell under the sway of two Englishwomen who set her on a lifelong course: Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel, founders of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Their mission was to gain the vote for women, which the prime minister, Herbert Asquith, had said might be taken care of in a future reform bill.

Having gone that far, however, Asquith stonewalled. The Pankhursts felt betrayed, but the prevailing mores posed a dilemma for women. Make your case gently, and you’re sure to be ignored. Cause trouble, and you’ll be denounced as ill-bred viragos. The Pankhursts opted to cause trouble.

Paul’s initial contact was with the elegant and brainy Christabel, who gave a speech in Birmingham that Paul attended. After moving to London, Paul took part in what the WSPU hoped would be the biggest pro-suffrage demonstration ever staged.

The WSPU did its part, turning out at least 40,000 marchers, but the prime minister continued to drag his feet. Paul became a member of the WSPU and volunteered in a number of capacities, including hawking the organization’s newspaper, Votes for Women. Her zeal soon brought her to the attention of the WSPU’s leadership, which invited her to join a deputation to lobby Parliament.

This was a riskier business than it might sound. The delegates were dead-set on meeting with the prime minister, and Paul was warned that their insistence might lead to arrests. She signed up anyway. Asquith refused to see the delegates, and the police formed lines to keep them at bay. When the women tried to push their way through, Paul and several others were indeed arrested, but the charges were dropped.

Paul was soon in custody again, for protesting a speech by the chancellor of the exchequer. Harsh treatment by her jailers prompted her to go on a hunger strike, which she maintained for 126 hours before being released. On learning that Paul would be in Scotland on holiday during the summer of 1909, the WSPU leadership asked her to visit Glasgow and disrupt a speech by the colonial secretary. With help from a friend, Paul climbed to the roof of the venue and, braving heavy rainfall, stayed there all night. Another arrest was followed by another hunger strike.

That November Paul outdid herself at the lord mayor’s banquet in London’s historic Guildhall. Disguised as charwomen, she and a colleague infiltrated the hall early that morning. They hid in a balcony, where at one point they were so close to being discovered that the cape of a policeman on patrol brushed against Paul’s hair. When Asquith rose to speak that evening, Paul’s companion took off a shoe and broke a nearby window, whereupon she and Paul yelled, “Votes for women.” They were arrested.

Paul launched yet another hunger strike, but this time the authorities were ready for her. Pinned down by three matrons, she was manhandled by a doctor, who, in her words, “pulled my head back till it was parallel with the ground. He held it in this position by means of a towel drawn tightly around the throat & when I tried to move he drew the towel so tight it compressed the windpipe & made it almost impossible to breathe.” A second doctor shoved a five-foot-long tube up her nose; when the tube reached her stomach, liquid food was poured in.

“While the tube is going through the nasal passage,” Paul recalled, “it is exceedingly painful & only less so as it is being withdrawn. I never went through it without the tears streaming down my face.” When word of Paul’s notoriety crossed the Atlantic, her mother reacted with amazement. “I cannot understand how all this came about,” Tacie Paul told a newspaper reporter. “Alice is such a mild-mannered girl.”

A month and 55 force-feedings later, Paul was released. She elected to return home and continue her education. But the Pankhursts had left a lasting impression, as they had on another foreign visitor at the time: Mohandas Gandhi, who concluded from watching the WSPU in action that he and his fellow Indians would win their freedom not by applying brute force but “by dying or submitting ourselves to suffering (i.e., by the use of soul force).”

Back in the States, Paul was invited to speak at the convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in Washington. President William Howard Taft’s opening remarks at the convention underscored how much work had to be done at home. It wasn’t just that Taft insulted the suffragists by comparing them to Hottentots (a derogatory term for certain African natives, viewed as the ultimate in backwardness). When some of his listeners hissed at him, newspapers denounced the outburst as unforgivably rude, and even Anna Shaw, NAWSA’s president, called it one of the “saddest hours” in the organization’s history.

Paul returned to Philadelphia and Penn, where in 1912 she earned her doctorate with a dissertation topic close to her heart: “Outline of the Legal Position of Women in Pennsylvania 1911.” Resuming her activism, she became chairwoman of NAWSA’s new Congressional Committee.

Although NAWSA had once favored a federal constitutional amendment to give women the vote nationwide, the proposal had languished on Capitol Hill. Led by the anti-hissing Anna Shaw, the organization had switched to a state-by-state approach. But gains were sporadic: by the end of 1912, women had the vote in only nine states, most of them in the West. And in some states the process was booby-trapped—failure to pass a state constitutional amendment could bar you from resubmitting it for several years. Paul urged NAWSA’s leadership to revert to the national strategy, without success.

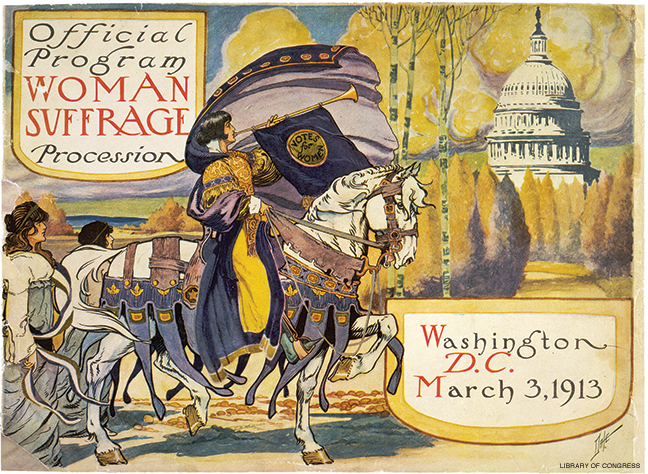

Paul took advantage of her new post in Washington to call for a suffrage march the day before the March 4, 1913, inauguration of the new president, Woodrow Wilson. Surprisingly, NAWSA headquarters in New York gave its blessing, and Paul got the route she wanted: along Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol to 17th Street.

A controversy arose as to whether African Americans should be allowed to march. Fearing the collapse of the whole enterprise if permission were given, Paul equivocated. In a rare instance of the national leadership’s being braver than Paul, she was told to be accommodating. According to Mary Walton, in A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot, “Alice’s failure to unreservedly welcome black marchers left a permanent stain on her reputation.”

In addition to all the other work of organizing a march, Paul had to raise money. Here she ran into luck. Alva Belmont, a New York socialite who was rich three times over—by birth, by marriage to a Vanderbilt, and by remarriage into the plutocratic Belmont family—gave generously, as she would do for Paul again and again.

As the big day drew near, Paul worried about security—several thousand women and men were expected to march—but the District’s police superintendent insisted that everything was under control. Events proved him woefully wrong. While the police either did nothing or made rude comments, male bystanders shouted insults at the marchers, got in their way, swiped their banners, threw lighted cigarettes at them, even struck them.

When the march was over, an estimated 100 people had been injured. In the sometimes topsy-turvy world of protest, however, the shabby spectacle counted as a victory. As Paul assured a sympathizer, “This mistreatment by the police was probably the best thing that could ever have happened to us, as it aroused a great deal of public indignation and sympathy.”

The march also seems to have rattled Woodrow Wilson, whose support, if obtained, might galvanize Congress to act. Afterward the president met three times with suffragists, Paul among them, but refused to back a constitutional amendment because he allegedly had too many more pressing duties.

For her part, Paul was running out of patience with NAWSA’s stodgy leadership. Without consulting them, she launched the Congressional Union, a membership organization devoted to pushing the federal amendment. While its bid to become a NAWSA auxiliary was under review, the Union adopted a new strategy of working to defeat anti-suffrage members of Congress at the polls. NAWSA objected to this as dirty pool, and the Union was denied auxiliary status. Paul had brought about a schism. Fortunately, Alva Belmont and her money defected, too.

Although Wilson continued to meet with the suffragists, he offered a new reason for not supporting a constitutional amendment: its inconsistency with the Democratic Party platform. After his re-election in 1916, members of the Congressional Union wangled invitations to his victory speech to Congress. As Wilson enumerated the initiatives for his second term, the women displayed a banner asking: “MR. PRESIDENT, WHAT WILL YOU DO FOR WOMAN SUFFRAGE?”

The Union made its home in Washington, where Paul and her lieutenants were beginning to look at the White House in a new way—as a backdrop for political drama. In January of 1917, they deployed pickets, or what The Washington Post called “silent sentinels,” at the house’s gates; one of their banners revived the question “WHAT WILL YOU DO FOR WOMAN SUFFRAGE?”

The novelty of appealing to the president at home drew widespread criticism, notably from The New York Times, which celebrated “something in the masculine mind that would shrink from a thing so compounded of pettiness and monstrosity.” Carrie Chapman Catt, Anna Shaw’s successor as head of the estranged NAWSA, called picketing “childish.” Even Tacie Paul balked. “I hope thee will call it off,” she wrote her daughter.

As a leader, Alice had become famous for her blend of dynamism and calm—one observer called it “the quiet of a spinning top.” But the wave of anti-picketing animus dismayed her, as witness her response to a timely check sent by Belmont: “We have received almost nothing but letters of sternest reproach since we started. It was indeed a joy to open your letter after all the other hostile ones.” The picketing continued.

In the meantime, several things had happened. Paul’s Congressional Union had merged with another group, the National Women’s Party, under the latter’s aegis. America’s entry into the Great War had become a matter not of whether but of when. And two major combatants had done right by women, as highlighted in a new banner raised outside the White House: “RUSSIA AND ENGLAND ARE ENFRANCHISING WOMEN IN WARTIME. HOW LONG MUST AMERICAN WOMEN WAIT FOR LIBERTY?” (Although Herbert Asquith was no longer British prime minister, his was the parliamentary motion that had introduced the reform.)

A few days later, Wilson unwittingly played into the suffragists’ hands. Always a sucker for a ringing phrase, the president declared in his war message that one of the causes worth fighting for was “the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own Governments.” Needless to say, the picketers threw those words back in the president’s face.

That summer a policewoman took it upon herself to arrest two of the White House pickets. This set off a rash of further arrests. Tried for what amounts to disturbing the peace, the protestors were sentenced to 60 days in the workhouse. The draconian penalty drew so much criticism that Wilson pardoned the women. But the resumption of picketing triggered new rounds of arrests, including that of Paul herself, who was force-fed and held in solitary confinement. As she and her fellow-prisoners held out for weeks and then months, the authorities found themselves caught between two wretched alternatives: indefinite force-feeding, with all the adverse publicity it was sure to engender, and multiple deaths by starvation. In late November, the government capitulated, freeing all the suffragists.

The pressure must have got to Wilson. With a war to wage and an election coming up in the fall of 1918, the president sought to rid himself of a distraction by endorsing the constitutional amendment favored by Paul and her colleagues.

You may recall that the usual path for a US constitutional amendment is fraught with fractions. The amendment must pass each house of Congress by a two-thirds majority, then be ratified by three-fourths of the states. On January 10, 1918, the House of Representatives took up the suffrage amendment and passed it by exactly the required two-thirds margin.

Early head-counts suggested an equally close vote in the Senate. The Woman’s Party wanted more from Wilson than just his endorsement: he should twist a few senatorial arms.

While he procrastinated, women rallied in Lafayette Park, across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House. The police, missing the point that the park was a less in-your-face venue than the White House itself, arrested 24 protestors. One of the “crimes” they were convicted of— “holding a meeting in public grounds”—was so preposterous that Wilson got them freed. Then, at last, he went before the Senate to advocate the amendment.

Nonetheless on October 1, 1918, it fell short by two votes. The following January, a last-ditch effort was made to pass it before that Congress went out of existence (otherwise the pro-amendment forces would have to start all over again with a new Congress). After the move failed in the Senate by a single vote, a Southern congressman consoled the women by saying, “Your being so annoying and persistent and troublesome … is what has put the suffrage amendment on the map.”

The last demonstration of the long campaign took place when the president spoke at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York on his way to the Versailles Peace Conference. Paul and five others were arrested but quickly released. The final tally for the two years since Paul had focused on the White House was 2,000 pickets, 500 arrests, and 168 jail sentences.

On May 21, 1919, the new House passed the amendment by a vote of 304-89, safely above the two-thirds requirement. On June 4, the Senate followed suit by the tighter margin of 56-25.

Whether 36 of the 48 states would ratify was anyone’s guess. In the event, however, state after state voted in favor until, in August of 1920, just one more was needed to put the measure across. Suddenly all eyes were on Tennessee, where the suffrage cause was about to produce a rare male hero.

Following passage by the state Senate, the amendment went to the House, where the vote ended in a 48-48 tie. Among the naysayers was a 24-year-old Republican named Harry Burn. A second vote was scheduled, and during the interim Burn pondered a note from his mother. “Hurrah and vote for suffrage,” she urged, “and don’t keep them in doubt.” When the roll was called, Burn changed his mind and voted aye. A few minutes later, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified.

Even Tacie Paul was moved. As she later summed up the moment, “Alice at last saw her dream realized.”

Although nothing in her later career can match the suffragist triumph, Alice Paul hardly sat still. She went on to earn a law degree; draft the first version of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923 (she lived to see it pass in 1972, but it was never ratified); found a World Woman’s Party in Switzerland; save the lives of 11 people, most of them Jews, during World War II; and see to it that a prohibition against employment discrimination on the basis of sex went into the 1964 Civil Rights Act. In old age, she returned to her native Moorestown, taking up residence in a Quaker nursing home.

Although in the 1910s it was feared that all those force-feedings had ruined Paul’s health, she lived to be 92. But perhaps such resilience should have been expected from a woman who had not only reshaped American political protest but also outgeneraled and worn down the president of the United States, the House of Representatives, the Senate, and 36 state legislatures.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is the author, most recently, of The Great American Railroad War.