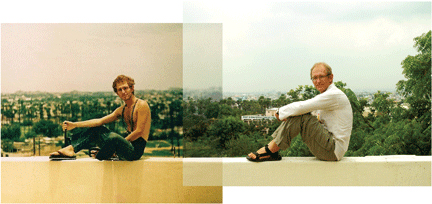

Revisiting the great Indian city where, 30 years ago, I came out of the Soviet cocoon.

By Alexei Dmitriev

I ran up the last flight of crumbling stairs in the back of the old house and stepped onto the roof. Following a short skirmish with laundry flapping in the wind, I advanced closer to the edge. Suddenly all of Hyderabad spread out before me. Everything was just as I remembered: the four soaring minarets of Char Minar, the arches and domes of the Jama Masjid. I’d known this would be a moment to cherish. What I hadn’t been so sure about was being able to find my way through the maze of the old city to this very rooftop after so many years. But memory favors the things we love.

To me Hyderabad has always felt like an enchanted city out of the 1001 Nights. Founded in 1591 and ruled by the Qutub Shahi dynasty for 170 years—until a traitor opened a side gate of the previously impregnable Golconda Fortress to emperor Aurangzeb’s army from the north—it sits at the crossroads of India. The north and the south meet here, as do Hindus and Muslims. The city’s early Islamic rulers—first the Qutub Shahis and later the Nizams of Hyderabad, who used uncut diamonds as paperweights—often appointed Hindus as their ministers. A composite culture arose that is still evident in the flavors of the cooking and in the local Deccani dialect of Urdu. This multiculturalism and tolerance shaped the ethos of Hyderabad. Few Indian cities have such a refined cultural heritage—or such a lavish material history. The mines near Golconda yielded the Hope diamond, the Orloff, and the famous Koh-i-Noor.

But the city carries a much deeper significance for me. Thirty years ago I spent two semesters at Osmania University in Hyderabad as an exchange student from the Soviet Union. After that incredible and transformative year, going back to the stifling Communist regime seemed like a move in the wrong direction. Not a small factor pulling me to the West was my Leningrad sweetheart, who by then had immigrated to the US, become a pre-med student at Penn, and traveled to Hyderabad to reignite the old flame. I decided to jump ship, and after two years of waiting in Greece for my American visa, settled into Penn’s South Asian Studies graduate program in 1985.

Last summer I came back with my 16-year-old daughter, Dora. The echo of long-past events that had profoundly changed my life reverberated in my memory, slowing my gait and pulling me in different directions at street corners, like a tourist who has strayed away from his group. Thirty years is a long time in the life of both man and city.

Hyderabad invokes nostalgia through architecture, arts, and the particular sophistication and grace of manners of its inhabitants which is known by the elusive Urdu term tehzeeb. It is this quality that today allows Hyderabad to preserve its genius loci despite the cars, pollution, and shiny shopping malls that have sprung up in my long absence.

I was happy to bask in the warm disposition of Hyderabad’s inhabitants, which quickly turned openly friendly once I began to sprinkle my speech with Urdu and Telugu words that popped up in my memory. As we drove from Golconda—where, just like 500 years ago, the clapping of hands at the main gate could still be heard at the very top of the 300-foot-high hill—we passed a wedding in full swing by the side of the road. No good parent should allow a daughter to leave India without a brief introduction to an “in situ” wedding ceremony. Accordingly, we were immediately ushered in and seated closer to the bride and groom than their parents.

The next day I took Dora to the Paradise restaurant, the Hyderabadi biryani and Irani tea institution. The cinema that gave the restaurant its name—where long ago I fell spellbound by Brooke Shields in Blue Lagoon, despite the deafening boos from a 100 percent male audience—was now gone, and the humble and quaint eatery I remembered transformed into a multi-floor feeding factory catering to lovers of Mughlai cuisine from all walks of life. In my student days, a filling meal at Paradise following two hours of Stallone and Bronson exploits next door was within my reach. But I coveted the air-conditioned Chinese restaurants that served beer and exuded unaffordable luxury, so I would order something inexpensive, and towards the end of my meal drop a dead cockroach on the plate to hoodwink a free encore from the embarrassed staff. What really worked against me back then was the scarcity of Chinese restaurants in the city! Yet now that they’ve become plentiful and affordable, I found kabobs from street vendors tastier and more rewarding.

We walked from Paradise to the railway station, where every other month I would board the night train to Madras to collect my stipend from the Soviet consulate. My idea at that time of opening a bank account into which the money could be wired made the Soviet consular officer accuse me of a penchant for capitalism: “You will be accruing interest in hard currency and it is not allowed!” He then recovered his fatherly side and added: “And of course, we’d love to see you more often just to make sure you are not too homesick.” In Madras a consulate car would drop me off at the VIP parking lot for the return journey, where to the amazement of coolies and beggars I would board the second-class coach and take my place among the Indian peasant and proletarian classes, since paying for the pleasure of staying connected to my caring handlers came out of my own pocket.

I was not completely uncared for in Hyderabad either. Two Soviet women lecturers at Osmania’s Russian department were told by the embassy to keep an eye on me. Soon they began commandeering me for their pearl-shopping sprees because I could haggle in Urdu. The frantic amassing of the Basra pearls for which Hyderabad is well known was a sure way to supplement their retirement income back in the USSR. Their other favorite pastime was “entertaining” Polish pilots who were teaching Indians to fly MiG planes at a nearby airbase. I found out about the trysts by chance when I asked a skinny gardener about a Polish Fiat parked outside. Next time I checked in with the Russian ladies I let them know that I was aware of the role the Polish gentlemen played in their lives, and as the result the ladies were quite pleased to never see me again.

Classes at the university would be often cancelled, either because the students would go on strike to protest the watchmen’s brutality or the other way around. On those days the city became my classroom. I was happy to ramble about the old quarters around Char Minar, inhaling the unforgettable mixture of street cooking, rotting trash, and urine steaming in the sun. I was never bored watching the lacquered bangles being studded with semi-precious stones at Lad bazaar, or sifting through bric-a-brac at the secondhand Chor (Thieves’) bazaar, or finding my way into serene courtyards of abandoned mansions where peacock shrieks would disturb the silence. I was happy to notice that little has changed in the old section of the city in the past 30 years. Even the tight grip of Dora’s hand on mine when she grew scared of getting lost in the alien crowd felt just like her mother’s 30 years ago.

Considering all the new construction, it was a miracle we did not get lost when I showed off in front of Dora by giving the driver directions to the university guesthouse where I had long ago stayed. Narsappa, back then a teenage peon who would sleep on the floor in the lobby and unlock the front doors when I showed up late at night, was now a balding deputy manager with a typical Indian potbelly. “Sir, you remember my name, sir!” he kept repeating while escorting us to the balcony on the second floor, with a sweeping view of the city in the distance. The palm trees had grown bigger, and the plain below, where cattle used to graze and villagers used to go to answer the call of nature, was all built up helter-skelter in the typical “construction resumes when we have money” manner, in which iron rods would stick out on the roof waiting for extra floors. I loved to come here in the evening to watch the red sun slide down behind the palm tree silhouettes, lie down on my foam mattress when the nights were breezy and wonder what my future had in store for me… “Sir, you remember my name!”

The city pulled out the weirdest occurrences from my memory. On this uphill street I had publicly humiliated an elderly cycle rickshaw driver by getting off and walking alongside to make his job easier. The poor chap got almost physical with me demanding I climb back in.

Of course I was not supposed to ride a rickshaw to begin with, the Soviet embassy official having warned us newly arrived students that using rickshaws amounted to human exploitation. But I rarely used public transportation in Hyderabad. Foreigners were such a rarity that when I needed to go somewhere it would suffice to simply show up at a curb with a raised hand, and within a minute be riding on the back of a Royal Enfield or Bajaj scooter holding tight to a new friend. After a while I started getting rides from people that had given me lifts before—in a city of 3.5 million souls! This was how I befriended a district liquor commissioner who wanted to practice his Russian, and to that end took me along on his inspections to the boonies in his official Ambassador, with lace-covered seats and an armed driver. We once raided a clandestine arak distillery, where the ill-fated bootleggers were more astounded by the sight of a whitey in their god-forsaken village than by the prospect of imminent arrest.

Today the twin cities, Hyderabad and Secunderabad, are close to being an eight-million-strong metropolis. A third area, with the catchy sobriquet Cyberabad, testifies to the city’s strong standing in India’s booming IT industry. And if 30 years ago a scooter that would comfortably carry a family of four through light traffic was a mark of the Indian middle class, today the streets are gridlocked with SUVs—albeit still with scooter souls, judging by how they weave in and out of the way of oncoming traffic. The new dynamism is pervasive and catchy, but to me the soul of Hyderabad appears as safe from the high waters of modernity “as a pearl in its oyster,” to use a metaphor for the city coined by a Persian poet.

While my stay in 1981-82 was far from bland, it could by no means match the trials that awaited me after I went underground to dodge repatriation attempts by the Soviet embassy and the Indian police: changing hotels every night, being swindled of all my cash in Mumbai, buying a used European passport in Delhi’s old market as mine had been blacklisted, dealing with counterfeiters who did a lousy job altering it, and finally using it to cross over into Nepal. I will never forget all that. But Hyderabad’s magic is what awoke my wanderlust and lit a lifelong love affair with Asia. More importantly, in one year it gave me a crash course in self-sufficiency, and other valuable capacities people acquire during their formative years in an unstructured and free world quite different from the one I was used to.

Which, strangely or perhaps not so strangely, was how Hyderabad seemed to strike Dora all these years later, encountering its chaotic freedom from the vantage of a quite different cocoon. “Paps, you chose a cool city for your jumping board to the West,” she said as we checked in for the flight home. “I myself feel like defecting here, rather than going back to my teenage suburban life.”

Alexei Dmitriev G’88 is a documentary filmmaker in Potomac, Maryland.