In February 2000, more than 11 years after Herman Atkins was wrongfully convicted of rape and robbery, he was freed by the State of California. New DNA tests had proved conclusively that the spermatogonial signature left by the rapist was not his. Yet even though he was exonerated, he left the state prison with nothing but the clothes on his back—and the memory of more than a decade spent behind bars for a crime he didn’t commit.

Marc Simon C’96 was a student at Yeshiva University’s Benjamin Cardozo School of Law when Atkins was released, and he makes it clear that meeting and subsequently befriending the former prisoner would have a “profound effect” on the film he would undertake. Simon had recently joined the school’s Innocence Project, which provides legal aid to prisoners wrongfully convicted of crimes, attempts to overturn their convictions through DNA testing of evidence, and works to implement reforms to prevent wrongful convictions.

“The work of the Innocence Project was so dramatic and cinematic in certain ways,” Simon recalls. “My first day of class, [Innocence Project co-founder] Barry Scheck walked in with an exoneree who had just been released that day from a New York prison after spending 19 years there. So in some ways the foreshadowing for the film was always there.”

The film is After Innocence, a riveting documentary that opened in New York in October and in Philadelphia last month, and will open in certain other parts of the country over the next three months (see www.afterinnocence.com for details). It follows the cases of seven exonerees, including Atkins, all wrenching examples of justice gone wrong. (Wilton Dedge, for example, served 22 years for sexual battery, aggravated battery, and burglary, even though he was five-foot-five and weighed 125 pounds, and the victim had told police that her assailant was six feet tall, big and muscular enough to throw her around easily.) The fact that one exoneree was a policeman at the time of his arrest and another was the son of a policeman makes it painfully clear that their nightmare could be anybody’s.

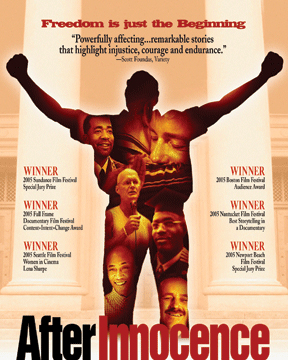

After Innocence has pulled in a slew of awards, including the Sundance Film Festival’s Special Jury Prize. Working with his partner, director Jessica Sanders, Simon was the film’s writer and producer, and was involved in pretty much everything—from attending all shoots to passing out fliers to writing grant proposals to editing more than 140 hours of footage down to a 95-minute film.

The documentary represents the confluence of several streams in Simon’s life. One is his longstanding affinity for the underdog, the guy who perseveres despite crippling odds. Another is his interest in films, which at Penn manifested itself in taking multiple courses in subjects ranging from screenwriting to film theory. (During his Penn days, those two passions came together in the figure of Rocky Balboa, one of his biggest film heroes.) A third is prisons. “I can’t explain it,” he says; “I just always had an interest in the prison-justice system, even as a kid.” Finally, there is the law, which led him to Cardozo, where it was only a matter of time before he would be drawn into the Innocence Project.

“As a student, I was struck by the fact that exonerations were being celebrated by the media and the public as success stories, as wrongs being righted,” he says. “The exonerees would leave the prison gates, be shepherded into press conferences, be on the covers of newspapers with their arms raised—and no one would analyze what happened two days later, when the press walked away. I learned that the exonerees were left with nothing. It was the ultimate injustice—not only were these people wrongfully convicted, but they’re being released without any assistance from the states that wrongfully convicted them.”

The “ultimate and distressful irony,” he adds, is that when the truly guilty convicts finally get out of prison, “they have help from an array of systems—that’s the parole system. But the exonerees were innocent—and they’re being released with no assistance.” (Many exonerees cannot even get their “criminal” records expunged by the very states that released them.)

The odds facing the prisoners —and the Innocence Project—are often overwhelming.

In Atkins’ case, the prosecution refused to allow access to the evidence, and only after the Innocence Project filed a motion—granted by the court—did they relinquish control of it. In Dedge’s case, the State of Florida asserted in court that they would oppose his release even if they knew he was absolutely innocent. Still, the Innocence Project has helped to exonerate more than 160 prisoners over the last decade, and is working to convince a number of key states (including Pennsylvania) to pass compensation legislation for those wrongfully convicted and to build support for the Life After Exoneration Program, which helps survivors of wrongful conviction re-enter society and rebuild their lives.

Simon, whose day job at the Dreier law firm in New York gives him the opportunity to do some “entertainment-related” legal work, hopes to focus on the film business in the future, and has a lighter television project in the works. But for now, he has his hands full with After Innocence.

“This has been all-consuming, emotionally and psychologically,” says Simon, who is in constant contact with the exonerees. “It can have a tendency to make a lot of things seem superfluous. This has been a journey—intensely emotional, intensely rewarding. But for me we’re really not at the end. The ultimate success is if the film makes a difference.”

—S.H.