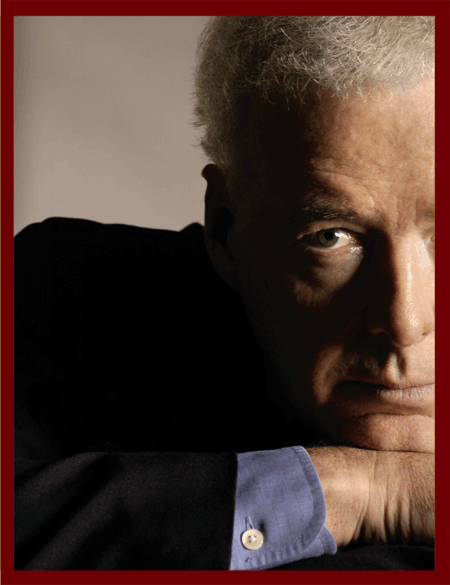

The writer once known as Brother Garrett brings a compassionate fervor to his creative-writing classes.

By Dan Kaplan | Photography by Candace diCarlo

Paul Hendrickson is, as per usual, leaping out of his chair. Within seconds, he is pacing around, manipulating his hands with impassioned gestures, shifting the tones in his practiced larynx from whisper to low-boom, hitting the students with what can only be called the Gospel of Journalism. If Hendrickson wasn’t going to don the frock and save some souls—a life-path he ditched weeks before taking his initial vows—it seems clear that he had to teach.

In today’s class, Penn’s most popular teacher of Creative Non-Fiction, whose frisky, unforgettable white hair is losing the inevitable war with his central scalp, has returned to the prime real estate in the focal chair of his Kelly Writers House classroom. In front of him and all of his students is a copy of Walker Evans’ and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and a section of a written documentary by a College senior named Adam Small. The first is a tome—Hendrickson calls it his “biblical talisman”—about the two men’s famous expedition into the lives of Deep South sharecroppers, full of Agee’s sensitive, often self-indulgent, always-lyrical writing and Evans’ sublime photographs. The second, which is about to be read aloud by its author, is a piece on a methadone clinic, and today’s section regards a particular classroom experience with blasé girls in a course on addiction at Penn. The book looks thick and imposing. Adam Small looks nervous.

Small’s writing is solid, but has lots of holes and is nowhere near as palpable as it could be, and the class knows it. At Hendrickson’s instruction “not to forgive a single word,” the well-meaning tiger sharks close in. None of it is painfully harsh, but none effusive, either. Hendrickson readily agrees with one of the most acute critiques. Sometimes Adam smiles and offers self-deprecating laughs; at others, he stares at the table, cups his chin in his hand and covers his mouth. Hendrickson senses Adam’s declining mood, shifts into fervid mode and goes on about the rage he could hear in the writer’s voice. One member of the class couldn’t hear the rage, and much of the rest of the class thinks the rage is misplaced.

At some point soon after the class has moved past Adam, a female student says something about being in the right place at the right time, and it strikes one of Hendrickson’s large repertoire of chords. His head moves forward slightly, his body leaning. The student comes to the end of her thinking, and he flies out of his chair and starts pacing again.

“A thousand times in my motley journalistic career, I saw it happen,” he says, adjusting his pitch so you have to know what it is. He follows up, his voice a mix of restrained awe and quiet intensity: “I put myself where the story was, and all of a sudden, it begins.”

If I’m in a reductive mood, I could say that Paul Hendrickson saved my life. It’s not that I’ve ever been suicidal, or even close: my lows are frequent but never get that low (thank God)—but anyone is aware that life can go in different directions, and the spring I took his class, everything was set up for me to take a dive.

In mid-August of the previous year, 2001, when I was in Central Park to pick up some tickets to a Chekhov play, I happened upon a murdered man whose bullet-induced death has made an occasionally fertile nest in my dreams. He was shot in the belly; I found him in the bushes with a tiny gun by his side and flies preparing the next brood in his shaved-bald, black scalp. The image inspired the first piece I wrote for Paul.

Incidents stemming from that same month gave me the subject for my third. It was about an actress ex-girlfriend for whom I still had profoundly confused feelings and a complicated relationship. A week and a half after finding the man I refer to as “The Dead Guy,” she and I had stood on the rock-covered roof of her beautiful apartment building on Houston and Elizabeth, and with the Twin Towers idling in the background, peacefully, she told me she had a rare illness. It was the same one that Jack Kennedy had had—Addison’s—and it was terrifying because I knew nothing about it except that it was rare and didn’t play nice with your adrenal gland. Three months later, at that exact same spot—whose tranquility had been detonated by two fireballs, leaping civilians, collapsing steel, and dust—she told me that what they thought had been Addison’s had turned out to be a kidney cancer that was in danger of spreading to her liver.

What I didn’t know when I wrote that piece was that the whole story was a lie, fabricated for reasons and with human capabilities that I question—futilely—to this day. But the questions were immaterial at the time: by that winter, a trio composed of the violent death I’d discovered, the realization of terrorist-based fears I’d held since high school, and the premature mourning of a girl I had once been in love with (and still half-was) had left me alternately reeling and numb.

Then I met Paul. After applying my way into his English 145: Advanced Non-Fiction class, I immediately bonded with him, as do so many of his students—so many it’s ridiculous to try to count—and we started what would become an intimate friend-slash-mentorship.

I’m one of those people who can put on a wiseass, extra-confident face to cloak the fear. Paul saw through it with a half-glance. And because he was born to take confession, most of the intimate details came from one side. I’d write him long e-mails about the fear and hurt doing noxious things to my brain, and he’d write back—usually that day—500-1,000 words loaded up with empathy and encouragement. He’d frequently read the classroom-relevant parts of my e-mails aloud in class, and, after I wrote letter-length reactions to other people’s work, he’d take me aside and tell me how impressed he was with my thoughtfulness and effort.

At that point in my life, I hoped and half-believed that I could be a writer—that I was, in fact, damn good—and needed someone to bolster my insecurities and affirm my half-beliefs. Paul was a natural for that role.

I took to calling him Dr. H in e-mails and in class, and he took to calling me Dr. Dan, or Dan-o, or sometimes the mixture of both. I considered myself one of his favorite and most talented students, ever, even though a girl named Katherine Newman C’02 had a bigger gift with language. One student who has insisted on anonymity has said that “he can be overly effusive, so you can’t know if he’s being genuine,” but I believed (and still believe) everything positive he told me about me. That he said it with a preacher’s passion mixed with paternal feeling did most of the trick. That he wore his own fragilities on his goofy baseball cap did even more.

The path that put Paul Hendrickson’s life on a trajectory that would later intersect and influence the trajectories of Penn students began shortly after he turned 21. At the time, if you told him that in 34 years, he’d be teaching privileged kids to write, he would have thought you insane.

The name then was Brother Garrett, not Paul. This was not because he’d experienced brain trauma and lost his identity—though in some ways you could say that maybe he had. It was because he, a former central-Illinois altar boy and the progeny of a Catholic pilot and more intensely Catholic housewife, was studying at Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity, where adolescent males went to grow into priests.

It was also where the seminary’s spiritual director had the young priests-to-be combat their sinful tendencies in a way that only a deeply repressed homosexual priest could. During the resurgent molestation scandals a couple years back, Hendrickson wrote about it like this in The New York Times: “I’d go in, sit in a green chair beside his desk, unzipper my pants, take up a crucifix, begin to think deliciously about impure things and then, at the point of full erection, begin to recite all of the reasons that I wished to conquer my baser self and longings. ‘Father, I’m ready now,’ I’d say. Having taken myself at his prompting to a ledge of mortal sin, I was now literally and furiously talking myself down, with the power of the crucified Jesus in my left hand. My director was always there, guiding me, urging me, praying with me.”

Hendrickson notes that he never saw lust in the priest’s eyes, but he put an end to the sessions when he was 20, and, within a year, six weeks before his vows, decided to take off. “Of course, some of it had to do with being 21 and wanting to get laid,” he allows, “but that way of life wasn’t working anymore. The Sixties had done [it]. That same revolution that was happening in the streets was happening behind the seminary walls. The dream just started to wither.”

When he bolted, the internal compass that all writers share began issuing directions. It told him to study literature, read what the masters had to say, and go from there. It pointed him to St. Louis University and Penn State and left him with a B.A. in English and an M.A. in American Lit.

Then it was time to do what he came for. Fiction? Nah: As he puts it, “I’m not a novelist because I can’t make up the plot.” He entered journalism, and had what any observer would call a meteoric rise.

Within four or five years of getting down and doing actual, hard reporting for newspapers of middling significance, he had caught The Washington Post’s eye. The Post figured he’d be a good fit for the “Style” section—as in lifestyle, not clothing and perfume. For “Style,” Hendrickson wrote features on subjects ranging from Ernest Hemingway’s mentally mangled offspring to a guy from the sticks who blew a hole in his neighbor over the neighbor’s pack of pain-in-the-ass dogs.

And so began a 23-year career as the newsroom’s “delicate flower” (the Post’s legendary editor, Ben Bradlee, called him that), writing heartfelt stories about sympathetic characters with mediocre life-chances, taking occasional time away to write books. Those times were frightening, because, as Hendrickson puts it, they’re “fraught with peril and you’re not making your paycheck.” In the first of those perilous periods, he wrote Seminary: A Search, an autobiography of his adolescence. It hit the scene in 1983 to some highly positive reviews and a sensationalized excerpt in Playboy, and made it to paperback, but not much further than that.

Next was Looking for the Light: The Hidden Art and Life of Marion Post Wolcott, a beautiful and sad book about one of the most talented photographers America’s ever had but neglected to notice. She, like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, photographed the desperate South during the Depression, but abandoned her art for a life of wifehood.

Looking for the Light, which came out in 1992 and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, was sandwiched between his efforts on a biography of Robert McNamara and five lives touched by his missteps and lies. The first time he tried to get it all down, in the mid-’80s, the hammer couldn’t find its way to the nail. It took him a decade and a large vat of boiling stress to hit it right. The Living and The Dead: Robert McNamara and Five Lives of a Lost War came out in 1996 to terrific acclaim. The New York Times called it “a work that approaches a Shakespearean tragedy”; The Philadelphia Inquirer used the word masterpiece and said that Hendrickson “has a gift with language that most writers can only dream about.” Although a reviewer on Amazon.com said it sometimes “approached bathos,” most gave it unabashed praise. It became a New York Times Notable Book, Salon.com’s non-fiction Book of the Year, and a finalist for the National Book Award—but lost, to James Carroll’s An American Requiem.

That November, the pre-winter D.C. air mixed with that gut-hollowing feeling that follows lining up a decade’s work to take one of book-writing’s biggest prizes and being shot down. He was out for a walk, having some thoughts.

One was that, after 22 years at the Post, he’d reached a point where—to borrow a line from a former colleague—“‘the form [became] as narrow as the width of a column:’ you have to write brick and mortar, declarative, expository information” and hold back the Hendrickson flair. Then there was the Voice of Middle Age, telling him he had to find a good place to put on that little bit of paunch and maybe go bald. His bank-account concurred: “My kids are coming up through college and I want to get a discount at school.”

With the middle-age angst and the bank account calling the shots, Hendrickson fired off an over-long and emotional letter, stapled on the Inquirer’s glowing review of his work, and posted it to Penn. Dr. Wendy Steiner, the Richard L. Fisher Professor of English and then-department chair, found the letter “extremely detailed and compelling and full of excitement at the idea of teaching.” That was in 1997, and by spring the following year Hendrickson was taking a weekly Amtrak from D.C. to teach his “test-me-out” writing class. After two years of abundant student praise, Penn made him full-time.

With the confidence of a secure appointment and an ever-burgeoning creative-writing program eager for new things, Hendrickson decided to create his own course. What if, he thought, every week of the semester, for any number of hours, students picked a subject, went after it, and then went back and back and back some more, documenting the life of a person or place, grimy nooks and all? And what if, while they were at it, they had to sit down and produce a 30-page story, work-shopping bits and pieces of it with their classmates as the semester went by? The code would be English 155: Writing in the Documentary Tradition, known to those who’ve been through it as “the doc class.” Both the doc class and its creator began a trajectory towards legendary status among those who fancied writing fact-based prose.

That trajectory got a boost when the Big Time Literary Awards finally caught up with a book that he wrote while teaching here. Sons of Mississippi, which Hendrickson decided to write after seeing a photograph of five white civil-rights-era sheriffs eagerly preparing for brutal mischief with a truncheon, investigated how the racism of the families in that picture mutated over a generation. Even though The New York Times said that its “argument fails, leaving [it] to claw at the surface of something that it never quite penetrates,” the work won many contrary opinions and ultimately the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Landing a big prize has led to all kinds of attention and paychecks to do things like fly-fish on a magazine’s tab and put down 10,000 words. Hendrickson was invited to pen the opening to Bound for Glory: America in Color 1939-1943, a book of color photographs taken by photographers working for the Farm Security Administration, as Marion Post Wolcott had. He is also teaching a new class, Photographs and Stories, which follows the dig-into-a-photograph formula he used to write Sons. (Some filmmakers are working on a documentary about that book’s characters.) He is also at work on a new book about Hemingway—“a lifelong obsession”—and his son, Matt, is a senior at Penn.

Hendrickson has become the centerpiece of Penn’s formal acknowledgement of nonfiction as a vital genre. Dr. Al Filreis, the Kelly Professor of English who serves as faculty director of the Kelly Writers House and director of the Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing, calls him “a perfect teacher of documentary-writing workshops,” and last spring, Hendrickson netted the Provost’s Award for excellent teaching, given to only two teachers a year. In a way, the compass has drawn a circle: After 23 years, he’s found a pulpit where, as his friend, poet and creative-writing program director Greg Djanikian C’70, puts it, “he can beautifully sermonize about the effects of language.” Of course, there’s more to it than a desire to leap out of a chair and fire off some passionately articulated words.

It’s my turn to take confession. Paul and I are sitting at a table outside Bucks County Coffee at 40th and Locust streets, and for the first time, I ask him if he gets off on the adulation. “I’ll own up to that,” he says. “Some of it really is the admiration, that kind of feedback and ego and narcissism: the narcotic of the guru, of the mentor.”

He’s wearing big-frame brown sunglasses, and when he says this—when he says anything during this interview—he never looks directly at me, sometimes aiming his words at the space in between us, right above the table, sometimes to his left, sometimes at the air around my head. Frequently, when we get on to personal matters, he changes the subject. When I ask a question he thinks is well-thought out, for example, he’ll say so—then digress to the subject of the most talented writers he’s seen since he’s been at Penn, compliment me on being among them, and start asking questions about me and my life-plans.

I’m ready for this. I’d read a previous profile of him in which the interviewer had found herself complimented, then turned around, revealing details about her personal life and going too far before realizing what he was doing to her. I keep the interview on track.

If he appears uncomfortable on the other side of the tape recorder, he is also incredibly honest. Knowing that administrators and alumni will read his words, he admits that he would have to quit if teaching ever road-blocked his writing; says big-ego things about his gift for “seeing a scene and capturing it in all of its fleshy detail”; and acknowledges that his “ego makes the engine go.” But he knows he can say these things, partly because his big ego can’t hide his raw sensitivity, and partly because he knows I love him and understand that he reformulates part of that guru-narcotic into a drug that lets him teach like hell.

Looking for someone who will say something purely negative about him has been a loser’s game; most who have anything bad to say usually qualify it with “let me just say he’s wonderful”; those few who don’t think he’s wonderful tend to fend off curious reporters; and those who think he’s overwhelming, tries too hard to be everyone’s friend, or imposes a certain style of writing won’t say so out loud.

But these negative voices represent a Yankee-fan-from-Boston minority. Inside the classroom he’s a teaching banshee, and he exhausts himself outside the classroom as well. Each week for the doc class, he’ll whip up a chatty little e-mail, 1,200 words long. It’ll start off celebrating the quality of the week’s session, then, say, wander from Jane Fonda to Saul Bellow, cite an obituary from the day’s Times,quote Hemingway, and, in the end, set the agenda for the next week. Then, if there’s any student e-mail—and since he’s teaching both the doc class and the regular Advanced Non-Fiction, there always is—he’ll turn it around in 24 hours.

The issues within these run the gamut. Some simply want help on a piece: a suggestion here, a pat on the shoulder there. Many others want the answers to life. To them, to us, Paul is a gentle and loving side character in the ongoing tale of our confusing existence, the one who always listens and dishes back paternal yet sensitive advice. We tell him about the pains of our romance lives, recurring nonsense with our families; some even share that they are mentally ill.

The self-revealing crowd blends with the students who wonder if they could and should get paid to write. To us, Paul is the Mentor. We want Paul to say that our stuff’s up to snuff and—later—try to help us get jobs. Assuming the student is worthy, he’ll do both on a reflex. Safe odds have it that very few, if any, professors at Penn know so much about the details of their students’ lives.

This kind of relationship can have a down side. As one student who considers herself quite close to him but insisted on anonymity put it: “He gets so close to his students that he has the ability to hurt them … he can write you a heartfelt letter and say he’s disappointed in you and you die inside.” But far more often, Paul’s method produces terrific results. That same student said: “He lets you have these dreams and is there as a support. Having that much faith in your ability to go out into the world and really write something is something I would only have the courage to do because of [Paul].”

I can say the same thing. When I met Paul, I was scared; scared of the world, obsessed with its apocalyptic destruction and the seemingly impending death of my ex-girlfriend. Events mostly outside my control had laced cement shoes onto my confidence, but throughout, Paul was there, writing e-mails, putting his arm around my shoulder, letting me know that if I put the work in, I had what it took to see a big light at the other side and kick some ass along the way. At first, I thought “f*** the light!” but with every e-mail, every glowing comment on a rough or final draft, every time he found a way to make me feel like I was the man, the concept of kicking ass along the way seemed less fanciful. I even believed it. Through a recommendation from him, I got my first two real-world, respectable-paycheck writing jobs, and even now, when I need the kind words of my mentor-slash-friend, all I have to do is compose an e-mail, and he’s ready to invite me to his office hours or take my call.

“On my best days as a writer and a teacher,” he wrote me in a recent e-mail, “I feel I’m doing something the tiniest bit priestly—with a small p.”

Can I get an Amen?

Dan Kaplan, winner of the 2003 Nora Magid Prize for promising nonfiction writers, was supposed to graduate from the College that year. He’s still working on it, but should be done any time now.