Doctors are worn down by paperwork and long hours, forced to focus on computer screens instead of their patients, plagued by feelings of eroding autonomy, traumatized by a pandemic—and trained to endure suffering with stoicism. What ails physicians bodes ill for their patients. Can the visual arts help revive their well-being? A year-long initiative from Penn Medicine and Philadelphia’s flagship art museums aims to test the theory at internet scale.

By Trey Popp | Images courtesy Barnes Foundation

Sidebar | The Inscrutable Wife

Lyndsay Hoy GM’16’s path to a medical career began on a Thanksgiving Day in Peoria, Illinois. She was 10 years old. Her grandparents were visiting from Canada, and the family was scattered around the house after dinner when Lyndsay passed through the living room and heard a strange sound. It was coming from the couch, where her grandfather lay motionless save for a guttural gurgling at his throat. Frightened by the unnatural blue-gray color of his skin, Lyndsay, an only child, ran to her mother.

“Then she got my father,” Lyndsay recalls. Dr. Hoy was a cardiac surgeon. Lyndsay had actually watched him operate before—but what happened next bore little resemblance to the calm and controlled setting of a routine procedure.

“He starts yelling these commands specifically to different people,” Lyndsay remembers. “He told my mom: ‘I need you to go to the kitchen and get me the sharpest knife you can find, and I need a straw.’ And then he turns to my grandmother and says, ‘I need you to get the phone and call 911, and then call our neighbor—the number is listed on the fridge. I need you to tell him to come over and give me some help.’ I just stood there, watching him delineate all these goals.”

After placing his father-in-law on the floor, Dr. Hoy used a steak knife to cut a hole in the man’s neck. Then he plunged his fingers into the airway and began removing chunks of vomit—on which Lyndsay’s grandfather had choked, possibly as the result of a stroke.

Lyndsay meanwhile was frozen in place, locked in her grandmother’s grasp as the scene played out in front of them: Dr. Hoy sticking the straw into the windpipe to blow air into the lungs; CPR chest compressions; the paramedics with their electroshock panels; and finally the declaration of death.

“She had her arms wrapped around me really tight, in this kind of hold, where even if I had wanted to go I don’t think I would have been able to,” Lyndsay recalls. “So we both sort of just stood there. And that feeling of helplessness, I didn’t want to feel that anymore. If anything like this ever happened again, I wanted to have some semblance of an idea of what to do.”

It was a pivotal moment. “It sounds traumatic, and it was, but what was more lasting and impactful for me was watching my dad suddenly transform into this role—not a father but a very capable physician acting in a moment of personal crisis.” He had not felt helpless at all. Even as the life slipped out of the body beneath him, her father had neither panicked nor flailed. He had been in command.

Eighteen years later, Lyndsay Hoy began the final phase of her own medical training, as an anesthesiology resident at the Perelman School of Medicine. Different specialties attract particular people for all kinds of reasons, but if any one characteristic exemplifies anesthesiology, it is an emphasis on control. Anesthesiologists are the ones who put you to sleep, restore you to consciousness, manipulate your breathing and blood pressure during surgery, and manage your pain after it. As she advanced through a “typical” first year of residency—“fun, scary, new, overwhelming”—these were the things Lyndsay wanted to master.

As the year progressed, she started to feel a strange sensation in her chest: a kind of sloshing that was especially noticeable when she rolled over in bed at night. After a while she asked her boyfriend—now her husband, and a cardiologist—to listen. His stethoscope could detect no breathing anywhere on her right side. The next afternoon she got someone to cover for her in the operating room so she could run down the Perelman Center escalators for a chest X-ray. When she returned a few minutes later, the surgical case was finished and the operating room was empty. She logged into her medical record to view the image. It showed a “complete whiteout” of her right lung, which a normal X-ray would have rendered transparently black. In a panic, she called her boyfriend, who showed his attending physician. Neither one liked the look of it. Lyndsay was going to need a CT scan.

What that revealed was not yet definitive, but it made one thing clear: whatever was going on in her body, Lyndsay was emphatically not in control. “What we saw on the chest CT were all these filigreed lacy cysts,” she remembers. “It’s objectively very pretty. But it’s terrible when it belongs to you.” Only a few days later did she discover how terrible. She was diagnosed with a rare, progressive, and incurable lung disease called lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). It left most patients dead inside of a decade. Lyndsay Hoy was 28 years old.

In LAM, uncontrolled growth of smooth muscle cells ends up riddling the lungs with cysts or holes. It can also strike the lymphatic system, blocking vessels that ordinarily carry chyle—a milky, fatty, protein-rich digestive product—to the bloodstream, where it plays important roles in nutrition and immune function. The sloshing feeling Lyndsay felt arose from a blockage in her thoracic duct, the largest lymphatic vessel, that was dumping chyle into the lining around her lungs. When her doctors went to drain it, two gallons spilled out.

As more began pooling into the same space, Lyndsay had a decision to make.

“If I only had 10 years left,” she thought, “then maybe this wasn’t the right path for me—especially given how physically, emotionally, and mentally draining residency is for anybody in any field, no matter what else you’re dealing with on the side.”

But with what she describes as a mixture of denial and desperation to cling to some semblance of ordinary life, she fixated on her training.

“I remember thinking: If I can just get through this rotation, if I can just get through this week, I will deal with all of it later—‘all of it’ being my physical exhaustion, my emotional exhaustion, and coming to terms with what it meant to have this chronic, progressive, potentially life-threatening diagnosis.

“It was procrastination writ large,” she adds. “But I needed to maintain some grasp of normalcy. And I think just continuing with my routine—waking up at 5:30, going in at 6:30, staying there for 12 hours—that was really my normal. If I just turned my life upside down, it would have felt like I was giving in to the disease.”

And that would have led to a harder question: “If I stopped, who am I and what would my purpose be?”

So she pressed on. After more chyle-draining sessions, she had a semi-permanent catheter placed in her chest so that the fluid could drip out of her body as she worked. It hurt. Her five-foot-nothing hummingbird frame made the bandage-covered tubing painfully impossible to ignore—especially when she had to push a heavy patient gurney, sometimes while holding IV bags aloft.

But what was really difficult was how isolated she felt, even after disclosing her diagnosis to all 26 members of her resident class, many of whom responded with care and grace.

“I was desperate for a sense of community, in any capacity,” she recalls. And that was largely absent from her training. “If you think about anesthesia, even though you’re part of a huge training program at a preeminent academic institution where there are literally hundreds of physicians doing the same thing you are, you actually don’t feel a sense of community.” A surgical team may have some camaraderie, and so might their allied nursing team, but anesthesiologists fly solo. “You don’t even have the opportunity to talk about anything that’s not directly related to patient care—How’s this week going for you? How are you? I wasn’t around colleagues or attendings who could help me feel less alone.”

In this respect, Lyndsay’s rare disease was pushing her toward a destination that is all too common among medical residents—and physicians in general: burnout.

In 2019 Medscape surveyed more than 15,000 doctors for its annual Physician Lifestyle & Happiness report. Nearly half of them reported feeling burned out—defined as “long-term, unresolvable job stress that leads to exhaustion and feeling overwhelmed, cynical, detached from the job, and lacking a sense of personal accomplishment.” About 5 percent reported clinical depression, and another 10 said they were colloquially depressed—“feeling down, sad, or blue,” but below the clinical threshold. The main causes matched those named in past years: the burden of bureaucratic paperwork, long hours, the increasing computerization of practice (especially the demands of electronic medical records, which have steadily transformed face-to-face patient interactions into face-to-screen encounters), and a general sense of lacking control and autonomy, or feeling “like a cog in a wheel.” Boomers especially lamented computerization. Millennial and Generation X physicians were likelier to cite lack of respect from administrators and colleagues. Women reported higher rates of burnout than men, and rates vary considerably by specialty. More than half of urologists reported burnout, but “only” about a third of orthopedists and general surgeons.

The consequences of burnout are well attested by a growing body of research. They include poor clinical care, increased medical and surgical mistakes, patient dissatisfaction, and workforce attrition. There is also some speculation that it can be contagious, as burned-out physicians negatively interact with coworkers while performing poorly at their jobs, creating a dysfunctional work environment that drags their colleagues down. It can take a heavy toll on physicians’ health and well-being. A 2015 article in the American Journal of Addiction reported that 13 percent of male physicians and 21 percent of females met the criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, a higher rate than the general population. At the extreme end lies a worse problem, which is that medicine consistently ranks among the occupations with the highest risk of death by suicide. In 2004, a meta-analysis of 25 studies determined that the suicide rate among male doctors is 40 percent higher than that of US men in general, and that the rate among female doctors is 130 percent higher than US women overall. An estimated 300 to 400 American doctors take their lives every year—or roughly double the number produced by a typical Ivy League medical school.

Doctors suffering from burnout cope in a variety of ways, and it is reassuring to learn, from the latest Medscape survey, that exercise is twice as common as drinking or binge eating. But the single most common coping mechanism that doctors reported last year was “isolate myself from others.” An even greater proportion—nearly two-thirds—say that they have no plans to seek help, because they are either too busy, intent on dealing with it by themselves, or feel they are not yet suffering enough. Apart from the stigma of seeking mental-health care, it is also notable that less than a third of survey participants reported that their workplace offered any kind of program to reduce stress and burnout—even at academic medical centers from which much of the research on its negative impacts has emerged.

The stress of medical residency eventually caught up to Lyndsay, who took a sabbatical year largely on account of her disease. Yet she was also lucky. In 2015, just a matter of months after her diagnosis, the FDA approved a compound called sirolimus—which was originally discovered in the 1970s on Easter Island and developed as an antifungal agent, but is now mainly used to prevent organ transplant rejection—for the treatment of LAM. The drug made her tired, and headachy, and its immunosuppressive properties filled her cheeks with cold sores, but it stanched the chyle leak.

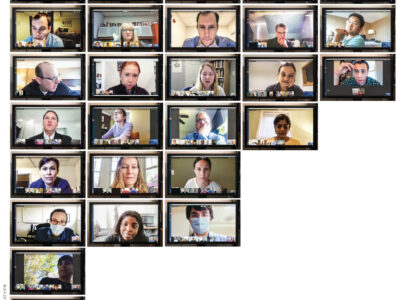

That may not have changed the likely endgame—a lung transplant—but it seemed to promise more running room. “If I was to be diagnosed with any rare disease,” she says, “this was the one to get.” Of the approximately 7,000 rare diseases that collectively affect some 25 million Americans, according to the National Institutes of Health, the FDA has approved treatments for only about 5 percent of them. Even locked in the rigid frame of a Zoom chat, Lyndsay mixes flashes of irreverence with the unaffected humility and disarming emotionality of someone who recognizes her curses and her blessings for exactly what they are.

The change wrought by a single pill with her morning coffee was astonishing. Yet that feeling of isolation continued to stalk her. Perhaps the most challenging moment came when she had to take care of a patient suffering from the same disease. “Her LAM was so far progressed that she was more or less on life support,” Lyndsay remembers. “It was like looking through a portal into my possible future.” She went through the motions, with professional detachment, until it was too much to bear. “Instead of offering support or talking to her, I ran away and locked myself in a call room,” she says. Eventually an attending physician from the ICU came in to talk her out.

LAM made everything “emotionally heightened” in ways that could be hard to handle, but what Lyndsay came to feel most strongly was that she was not unique: “Everybody is dealing with some sort of pain.”

So when she completed her training, and was asked to join Penn’s anesthesiology department, she resolved to do something about it.

“When I was an attending, I started searching for what kinds of things were being done to help people feel less alone. And not even necessarily people in my situation, but medical trainees in general—because I thought it was just such a hard, lonely, and isolating experience.”

And that search led her to Horace DeLisser M’85 GM’88 and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Horace DeLisser is a pulmonologist and the associate dean of diversity and inclusion at the Perelman School. In the early 2010s he’d gotten involved in a project spearheaded by two medical students—Jaclyn Gurwin C’11 M’15 GM’19 and Stephanie Davidson M’14—who wanted to see if structured engagement with visual art could improve clinical observation skills. They piloted a six-session course for first-year medical students at the PMA featuring close inspection and facilitated discussion of paintings.

As reported in the journal Ophthalmology, participants registered significant improvements (versus a control group just given free museum passes) in describing retinal pathology images and photographs of eye disease.

The idea of using art education to bolster clinical skills was not entirely new. It is often credited to a Yale dermatology professor named Irwin Braverman, who in the late 1990s became concerned that dermatology residents seemed unable to adequately describe what they saw on patients. Hypothesizing that teaching them how to inspect and describe paintings might improve their visual chops in the clinic, he helped to create a workshop at the Yale Center for British Art. After positive feedback—along with modestly positive clinical-observational results reported in JAMA in 2001—Yale eventually made it a required course, and nearly 70 medical schools around the world have since established similar (mostly elective) programs.

In recent years, interest has grown about whether visual art—among other aspects of what have been dubbed the “medical humanities”—might also be a way to reduce stress and burnout, while fostering empathy and interpersonal skills. By the time Lyndsay came across him, DeLisser had pivoted in just that direction. In 2017 he invited her to participate in a new project at the art museum, titled FRAME: Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education. Co-developed with Perelman faculty Andrew Orr, Nazanin Moghbeli, and Amanda Swain—along with PMA art educators Barbara Bassett, Suzannah Niepold, and Adam Rizzo—it aimed to create a “reproducible, evidence-based workshop utilizing artful thinking routines to prepare trainees to combat burnout with reflection, perspective-taking, and community-building.” This iteration featured just a single four-hour session for internal medicine residents, who were asked to do things like describe a painting to a blinded partner who would in turn attempt to draw it sight-unseen, and to adopt and explore the perspectives of various figures depicted on a canvas.

It proved a watershed moment for Lyndsay, who was especially captivated by an exercise in which participants wandered the contemporary-art galleries in search of a painting or sculpture that resonated with a specific prompt: for example, Find an artwork that speaks to a professional experience you have had with suffering; or Find an artwork that reminds you of a transformative or affirmative experience you have had at work. After 15 minutes of looking and reflection, the trainees then acted as a tour guide of their chosen object.

“It was just a fascinating exercise,” she says. “The participant acts as a docent for that piece to the group—not speaking about the provenance of the artwork, so much as the emotions triggered by the piece itself, and then sharing what is usually a personal anecdote, often clinical, to the group. And that’s a powerful moment for creating community.”

Lyndsay had a lot of feelings to work through—and insights to offer. Some of the deepest stemmed from the “disquietude and uncertainty” she had experienced as a patient. To be a physician with a chronic illness, she wrote a year after her diagnosis, was like being haunted by the “Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come”:

“Those worst-case scenarios that you try to push to the far corners of your mind can play out on a daily basis at work. You see the worst of the worst: intensive care patients on a ventilator battling infections, bleeding disorders, lung diseases, and cancers. You watch them languish day after day until there’s barely a person left. You may even be taking care of someone with the same disease as yourself,” she reflected. “You mourn for them. You try to comfort their families. You fear for yourself.”

You also—she came to believe—have the opportunity to become a better doctor. Which often was a matter of slowing down and tending to needs that had previously struck her as not being doctors’ work at all. “Smaller gestures are so undervalued in clinical care,” she says. “Before I was a patient, I never realized how cold it was to be in a hospital gown. So now, whenever I wheel my patient back in the operating room, I always get them an extra blanket. It’s typically a gesture that a nurse would do—these sort of comfort-care measures that I think a lot of physicians think is beneath them, or consider a housekeeping responsibility. But I will go get blankets from the warmer, and I will bundle them up and kind of tuck them in. And they love it! Even men my father’s age, they just smile! And if you need tissue, I will get you tissue. Just because my name ends with MD doesn’t mean that I’m above doing these smaller things. If you want me to hold your hand, I will hold your hand. If you want me to pray with you, I’m not religious but I will pray with you, I will listen to what you want to say. Because those things were done for me, and you don’t really get it until you’ve been there.”

One of the most meaningful professional compliments she ever received echoed this attunement to the often undervalued “softer” side of medicine. It came when a mentor welcomed her to the Perelman faculty with what might strike some as a throwaway phrase: “You will bring heart to this department,” he told her.

“Had I never gotten sick,” Lyndsay says now, “I don’t think he would have ever said that to me. Because I don’t think I would have been the kind of person he would have said that to.”

Having a “dual identity” as a doctor and a patient meant being “exposed to this entire spectrum of emotions and grief and sadness and having to reflect,” she explains. But that could pave the way toward a more deeply humanistic approach to medical practice—one that’s instantly recognizable to anyone who has been cared for by an extraordinary physician, but that formal training could do more to cultivate. “I felt like I was having to navigate a lot of uncertainty, and trying to derive meaning from, and forge connections through, vulnerability,” Lyndsay reflects. “Which I came to realize is quite powerful. And the medical humanities are a really wonderful conduit to do so.”

With DeLisser’s blessing, she tailored the FRAME format for anesthesiology residents and attending physicians, to whom she offered it as an optional activity on a Saturday afternoon. The timing meant people would come only if they really wanted to—since it would entail sacrificing one of the most valuable things in a resident’s life: a weekend free of being on call. The inaugural workshop set a pattern that would carry over to subsequent weekends: there was plenty of demand to fill up 20 slots, and nearly all of it came from women, most of whom were minorities.

That struck Lyndsay, who identifies as a Japanese American, as evidence of an unmet need. “I think there is some sort of lack of support for those particular trainees that’s not being addressed through the formal curriculum.”

If so, it overlaps with a perception among a growing number of practitioners, over the past few decades, that traditional medical education suffers from a broader deficiency: a disproportionate emphasis on technical proficiency at the expense of interpersonal competence; and an underdevelopment of empathy, resilience, and the capacity for self-care.

Among other things, the communal aspects of the museum workshop provided a space in which physicians and trainees could reveal anxieties and uncertainties whose public expression remains taboo in a profession that aspires to authoritative knowledge while holding itself to a zero-mistake standard. Admitting vulnerability is a tricky thing for doctors, whose effectiveness is directly related to the confidence they are able to inspire in patients. Few physicians relish disclosing weakness to one another, either. Yet the fear of being wrong, or of making a decision that leads to bad results, is in no way restricted to trainees. When late-career physicians speak safely among themselves, their egos secured by distinguished careers, it is not uncommon for them to marvel at the dogged persistence of that fear—which is renewed by every novel diagnostic puzzle, or fresh exception to a general rule.

“There is a culture of stoicism and selflessness that in some ways is inherent to what we as a society expect from physicians,” Lyndsay reflects. “Put your own problems aside. The patient always comes first. But when does that become a little more nuanced? And is that really the expectation we should be holding ourselves to? Because that’s why work hours are violated. That’s why residents aren’t taking care of themselves. That’s why some of them kill themselves. Is that what we want to ingrain in our trainees as the honorable way? If you’re not taking care of yourself, you can’t take care of other people. I don’t want a doctor who hasn’t slept in 36 hours taking care of me, I can tell you that. Or someone who’s morbidly depressed and is relying on alcohol. And it’s not because I don’t trust them; it’s because they have unresolved issues that they have, for whatever reason, been taught to not address.”

If there has ever been a time when physicians stood to gain from even a modest improvement in their ability to cope with such pressures, it is the present moment. This spring, doctors and nurses in some COVID-19 hotspots were literally climbing over critically ill patients to reach even sicker ones, as refrigerated trucks waited outside to store the dead. Frontline physicians spent the early weeks rushing patients onto mechanical ventilators—only to realize in retrospect, as more was learned about the paradoxical aspects of this virus, that they may have been speeding many of them to their graves. Healthcare workers have sustained trauma on a scale whose closest precedent in living memory is probably MASH units during the Vietnam War. Several months into the pandemic, a survey of US doctors by Physicians Foundation found that nearly 60 percent of respondents reported burnout, and 38 percent said they wanted to retire within the next year—more than twice as many as said so in the biennial survey’s previous iteration. Lyndsay may find herself unwillingly among that number. In light of a LAM-related scare last November, which led her to double her daily dose of sirolimus, she has removed herself from clinical duty. Anesthesiologists routinely perform aerosolizing procedures, and COVID-19 is especially perilous to anyone with an incurable progressive lung disease.

A 2019 analysis of the original FRAME workshop, published in Advances in Medical Education and Practice, found that it led to modest decreases in measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. In a review article the same year, the same team—led by Moghbeli and Neha Mukunda M’19—assessed the empirical impacts of 11 visual-arts educational programs at medical schools around the country. They found reasonable evidence to support clear positive impacts on clinical-observation skills, but that benefits pertaining to resilience, wellness, empathy, and communication skills (which are objectively harder to measure) were attested mainly by “anecdotal experience.” Some studies have demonstrated empirical impacts in those domains, but drawbacks like small cohorts and the lack of control subjects restrict the generalizability of their findings. Unanswered questions included the durability of anecdotally reported effects, and the “dose” required to produce them. “It is clear,” the authors concluded, “there is a need for more robust, evidence-based approaches for using visual arts instruction in the training of medical students.”

In August, Penn launched a yearlong initiative to connect medical practitioners with visual art at internet scale. Rx/Museum is a pilot program of the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, led by the University’s Health Ecologies Lab and the Center for Digital Health at Penn Medicine, in partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Barnes Foundation, and the Slought Foundation. It is codirected by Lyndsay Hoy and Slought executive director Aaron Levy, who is a senior lecturer in English and History of Art at Penn. Like the workshops described above, it aims to foster “clinician well-being and a humanistic practice of medicine” through guided encounters with visual art. Every Monday for 52 weeks, subscribers (or anyone who visits the website, RxMuseum.org; the content is free either way) receives a curated image framed by two short textual accompaniments. One amounts to an art-historical introduction to the weekly artwork, and the other invites reflections keyed specifically to an issue or issues relevant to clinical practice. (See Sidebar.)

“It’s incredibly difficult for providers to have time to attend museums and participate in the civic life of the city as much as they’d like,” says Levy. “We know that there are all these proven benefits to that exposure—with regard to dealing with ambiguity and so much else. But it’s difficult to visit these institutions. So the genesis of this project was: What if we were to bring the museum to the hospital?”

“Each week people receive a dispatch,” Lyndsay explains, “an essay intended especially for providers but open to all, that hopefully will further sensitize recipients to think more deeply—not just about the arts and humanities, but how they communicate with each other and how they participate in their communities.”

The art ranges from Horace Pippin to Picasso’s Blue Period to a still image from Gaza-based filmmaker Mohamed Jalaby’s 2016 documentary Ambulance. Befitting what is in part an educational initiative, the textual accompaniment was developed with substantial participation from students. Undergraduates from Levy’s standing English course on the literature of care contributed, alongside urban studies and fine arts students as well as medical students.

“We’ve set ourselves a challenge on the one hand to write in a way that’s art-historically competent,” Levy says. “And at the same time, to read them in a radically contemporary way that connects these works and the issues they raise to challenges that are occurring in a medical context. Many providers are incredibly excited about engaging the arts, but often intimidated. So through this deft weaving of art history with contemporary reflection in a medical context, we’re really trying to render it more comfortable to engage the arts. To find it almost practical and useful.”

Rx/Museum has been in the works for two years. “But we were excited to launch this project amidst the pandemic,” Levy says, “recognizing the challenges that providers and caregivers are facing right now.”

In September, the Association of American Medical Colleges conveyed their intent to include Rx/Museum in its arts-and-humanities digital guide for medical educators. That prompted Lyndsay to consider creating a lesson plan or curriculum to accompany the website.

“Ultimately,” she says, “our hope is that this can mitigate the challenges and pressures and severity of being a provider—in these times but also in all times, where there’s daily exposure to grief and trauma and loss. That is an incredible burden, and an incredible sacrifice that often goes unacknowledged. We hope this project offers solace, and support for that invisible burden.”

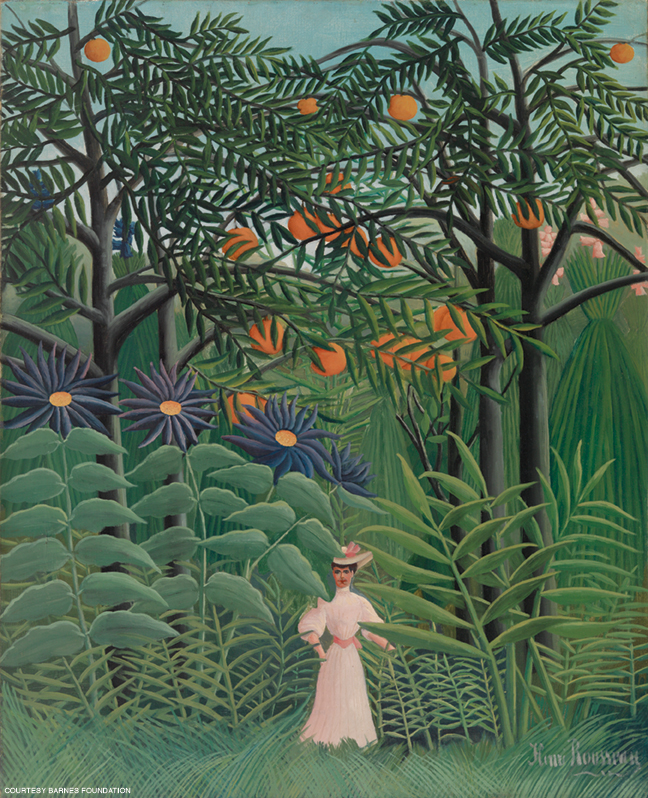

The Inscrutable Wife

Each week Penn’s Rx/Museum initiative pairs an artwork with historical context and reflections keyed to medical providers. Here’s one, republished by permission of Rx/Museum.

Wife and muse Madame Cézanne remains an opaque, diminished figure in the art world. Née Marie-Hortense Fiquet, “Hortense” means “hydrangea” yet this unsuitably named saturnine sitter appears composed, motionless, and bored in over forty of Paul Cézanne’s (1839–1906) portraits, drawings, and watercolors. Here, she is painted in a predominantly cool palette of blues and greens, complemented by warmer hues of umbers and pinks that vertically cap and contain the figure. Her signature tight bun (there is only one portrait of Mme Cézanne with her hair down) elongates pictorial height. Crossed arms enclose the figure, emphasizing an overall pyramidal form. Her face is mask-like and anonymous.

The couple first met in 1869—she was 19 years old and working as a bookbinder, Cézanne eleven years her senior. Claiming his authoritarian father would disinherit him, Cézanne insisted their relationship and eventual child remain a subterfuge from his family for over a decade. They married after more than fifteen years of secrecy, likely to legitimize their son as heir to the Cézanne estate, but continued their baseline marital separation—Mme Cézanne in Paris with Paul Jr., Cézanne at his family home in Aix-en-Provence. Nicknamed “La Boule” or “the ball” for her notoriously orb-shaped head, Mme Cézanne was ridiculed and belittled by Cézanne’s friends for her sullen, matronly visage and taciturn demeanor. Baseless rumors such as her absence at Cézanne’s deathbed due to a pressing dressmaker appointment in Paris further maligned her as a discontented, self-possessed shrew. At the time of his death in 1906, Cézanne had written her out of his will.

Cezanne was known for his distinctly ‘anti-biography’ approach to portraiture and agonizingly slow painterly process. Mme Cézanne would pose for hours while her husband painstakingly deliberated every detail, sometimes pausing for over twenty minutes from one brush stroke to the next. Yet the time intensive portraits reveal little about her true nature or the emotional tenor of the marriage. Like Mont Sainte-Victoire, Mme Cézanne is as an abiding presence, a landscape rendered without affectation — form over flesh, identity subsumed into objectivity.

Reflections …

In 1889, Sir William Osler delivered his now canonized speech entitled “Aequanimitas” to the graduating medical school class of the University of Pennsylvania. He stressed that “a certain measure of insensibility is not only an advantage, but a positive necessity in the exercise of calm judgment.”

Does Cézanne’s detached, restrained approach to portraiture of even his wife embody a similar spirit of equanimity? Does this method reflect a callous lack of sentimentality and joie de vivre, or a desire for seeking a deeper truth?

Do healthcare providers balance a similarly fine line of acknowledging personhood while maintaining clinical equanimity in the patient encounter? Does that balance tip in any one particular direction depending on the clinical course of the patient or duration of time spent caring for them?