How Penn’s foremost expert on bankruptcy law became one of the most surprising voices in contemporary evangelical Christianity.

By Trey Popp

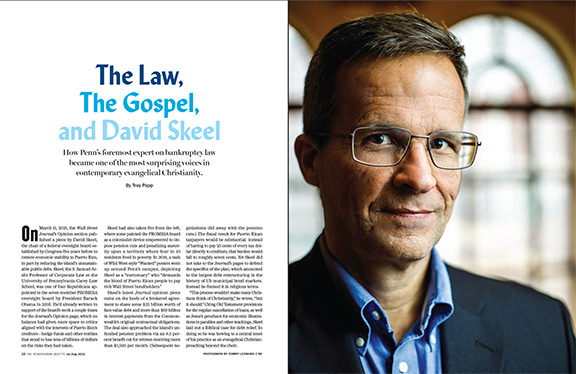

Photography by Tommy Leonardi C’89

On March 11, 2021, the Wall Street Journal’s Opinion section published a piece by David Skeel, the chair of a federal oversight board established by Congress five years before to restore economic stability to Puerto Rico, in part by reducing the island’s unsustainable public debt. Skeel, the S. Samuel Arsht Professor of Corporate Law at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, was one of four Republicans appointed to the seven-member PROMESA oversight board by President Barack Obama in 2016. He’d already written in support of the board’s work a couple times for the Journal’s Opinion page, which on balance had given more space to critics aligned with the interests of Puerto Rico’s creditors—hedge funds and other entities that stood to lose tens of billions of dollars on the risks they had taken.

Skeel had also taken fire from the left, where some painted the PROMESA board as a colonialist device empowered to impose pension cuts and penalizing austerity upon a territory where four in 10 residents lived in poverty. In 2018, a rash of Wild West-style “Wanted” posters went up around Penn’s campus, depicting Skeel as a “mercenary” who “demands the blood of Puerto Rican people to pay rich Wall Street bondholders.”

Skeel’s latest Journal opinion piece came on the heels of a brokered agreement to shave some $25 billion worth of face-value debt and more than $50 billion in interest payments from the Commonwealth’s original contractual obligations. The deal also approached the island’s unfunded pension problem via an 8.5 percent benefit cut for retirees receiving more than $1,500 per month. (Subsequent negotiations did away with the pension cuts.) The fiscal result for Puerto Rican taxpayers would be substantial: instead of having to pay 25 cents of every tax dollar directly to creditors, that burden would fall to roughly seven cents. Yet Skeel did not take to the Journal’s pages to defend the specifics of the plan, which amounted to the largest debt restructuring in the history of US municipal bond markets. Instead he framed it in religious terms.

“This process wouldn’t make many Christians think of Christianity,” he wrote, “but it should.” Citing Old Testament provisions for the regular cancellation of loans, as well as Jesus’s penchant for economic illustrations in parables and other teachings, Skeel laid out a Biblical case for debt relief. In doing so he was hewing to a central tenet of his practice as an evangelical Christian: preaching beyond the choir.

“The effort to restructure the debt in a way that balances the importance of contractual promises with Puerto Rico’s desperate need for a fresh start,” he concluded, “may be the most Christian activity I’ve ever been involved in.”

Skeel’s resume abounds with more conventional Christian activities. For 17 years he has been an elder of Philadelphia’s Tenth Presbyterian Church, whose Christian high school he also served as a trustee. He’s spent more than a decade on the board of directors of God’s World Publications, the publisher of World magazine, whose motto is “Sound journalism, grounded in facts and Biblical truth.” In 2014 Skeel authored True Paradox: How Christianity Makes Sense of Our Complex World, a slim volume of personal reflection and light-footed theological commentary in the vein of C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity.

Skeel wasn’t asked to help resolve Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis on account of his faith. He has been teaching and writing about bankruptcy law for far longer than he has engaged in Christian apologetics. In 2001, after a dozen years of wide-ranging academic scholarship in the area, he authored Debt’s Dominion, a 200-year history of US bankruptcy codes. Since then he has become an outspoken advocate of permitting states to declare bankruptcy [“Gazetteer,” Mar|Apr 2011]. At Penn Law his teaching load includes courses on bankruptcy, global corporate governance, and sovereign debt restructuring.

But in recent years Skeel has increasingly used his legal scholarship to advance a view of the law rooted in theologically conservative evangelical Christianity. This is partly intriguing on account of which areas of law attract his attention. The lion’s share of US legal commentary involving religion deals with the First Amendment’s Establishment and Free Exercise clauses. Skeel focuses virtually anywhere else. Christianity and the large-scale corporation. Christianity and bankruptcy. Christianity and criminal law. In a recent contribution to Pepperdine Law Review, he contended that contrasting theological frameworks left American evangelicals “Divided by the Sermon on the Mount,” with political ramifications that might help to explain many “evangelicals’ embrace of Donald Trump, despite his obvious flaws and their insistence two decades ago that a president’s character is essential.” He has written shorter pieces for the popular press addressing questions like “Was it Immoral for American Airlines to File for Bankruptcy?” (No, he argued to the readers of Christianity Today.) Taken as a whole, this growing body of work comprises a project to rectify a decades-long deficiency he has dubbed, in the title of another law review article, “The Unbearable Lightness of Christian Legal Scholarship.”

As an attempt to expand his field’s scholarly boundaries, this project is noteworthy in a similar way to the emergence of economics-orientated legal analysis at the University of Chicago in the 1950s and ’60s, or critical race theory in the 1970s and ’80s. Skeel is one of a small number of academics developing this Protestant evangelical approach to contemporary US law, and it is too early, of course, to know how much or little influence they may come to have. But what makes Skeel’s contributions especially interesting is how often his understanding of theologically conservative Christianity produces conclusions that run counter to the dominant strain of legal and legislative activism among American evangelicals, in areas ranging from vice regulation to abortion.

Contemporary evangelicals have a “tendency” he says, “to think that anything that’s immoral should be illegal—that the legal system should completely track our system of, or our common understanding of, morals. And I strongly disagree with that.”

Making his case for Christianity in True Paradox, he stated it strongly indeed: “When Christians seek to usher in the kingdom of God through law, they are denying Christianity’s teachings, not promoting them.”

A Disciple’s Path

Like many American evangelicals, David Skeel came to Christ in a roundabout way. The son of a teacher and an Air Force doctor, he spent his childhood trailing his father’s military assignments: Washington, DC; central California; Michigan; the Philippines; northern California; and finally Augusta, Georgia, where his dad left the service when David was in middle school.

One setting into which the family rarely ventured was a house of worship.

“I was inside a church maybe three or four times in the first 18 years of my life,” says Skeel. “We were not even Christmas-and-Easter Christians.”

By the time he enrolled at the University of North Carolina in 1979, his obliviousness to religious life was impressive even for a kid who’d never gone to Sunday school. It came to a head during a class discussion of a short story called “The Ram in the Thicket,” by the 20th-century American novelist Wright Morris. The titular reference to Abraham’s narrowly averted sacrifice of Isaac was completely lost on Skeel. “I had no idea what that was about—even when the story was discussed,” he recalls. “I had no familiarity with it at all.”

Among other things, that was an embarrassment. So the duly humbled English major made a resolution: “The Bible might be just a complete crock. It may be all mythology and not worth reading. But I needed to at least know what was in it. And so I decided to read the Bible.”

Skeel traveled his personal road to Damascus the summer after his sophomore year, in a van that he and two buddies drove across the country for a vehicle-transfer company whose reliance on collegiate would-be hitchhikers did not bode especially well for the firm’s long-term viability. “By the time we got to Las Vegas, the van was still running, and it still looked the same,” Skeel chuckles, “but I’m quite confident it was not the same van anymore.”

More importantly, he wasn’t the same anymore, either. When it wasn’t his turn to drive, he sat in the back, reading the Old Testament from page one. “And by the time I was not even finished with Genesis, I just knew in my heart it was true,” he remembers. “I had never read anything like it. It spoke to me about who I am, and what it means to be human, in a way that just completely blew me away.”

It was the beginning of a journey that led to Skeel’s rebirth as a theologically conservative Protestant who accepted the Bible as the “true and authoritative” source of teachings that form “the basis for everything else.”

The notion of Biblical “truth” attracts a certain amount of facile derision as a simpleton’s credo. After all, if God made the plants and animals before creating mankind in his own image, as described in the first chapter of Genesis, how could God also have created man before the plants and animals—as described in the second chapter? And did 42 generations separate Jesus from King David (as in the Gospel of Luke), or just 28 (as in the Gospel of Matthew)? Does the Bible’s “authoritative” nature extend to the Levitican prohibition against wearing garments woven from two kinds of materials? Or God’s insistence to a compliant Moses that a man caught gathering sticks on the Sabbath be stoned to death?

For Skeel, though, the Bible’s thought-provoking inconsistencies, as well as its disconnects with some contemporary mores whose wisdom he had already begun to question, were marks of a text that tackled the complicated nature of human existence head on. “The psychological complexity of Christianity was really powerful for me, as was the complexity of the language in the Bible,” he said in an interview some years back. “Truth can’t be conveyed in a single genre, so the Bible’s mix of genres, language, and images is part of the evidence for its veracity.”

Skeel doesn’t go in for the hallmark literalism of Christian fundamentalism. “I don’t believe creation took place in six 24-hour days. It just doesn’t make sense,” he says. “My view is that in the opening chapters of Genesis, for instance, God is not trying to give a recipe for creation; I think he’s telling us something about who he is and what creation is. So in some ways it’s a matter of genre: What’s God trying to do? Is this poetic, is it literal? Someone like me tends to view genre as a very important interpretive tool.

“I’m very much evangelical,” he concludes, “but very much not fundamentalist.” Yet he also rejects the theologically liberal urge to discard or “neutralize” elements of scripture that clash with present-day secular values. “If you read the Bible, and it says something that you don’t like—and no matter how you read it, you can’t read it another way—someone who believes it is authoritative concludes that it is binding, even if they don’t like it, or even if it’s out of step with modern life.”

As his spiritual awakening progressed, Skeel meanwhile fell into the grip of another captivation: bankruptcy law. This too was an unexpected development.

“Like most literature majors who wind up in law school,” he observed in the preface to Debt’s Dominion, “I knew little about business and finance, and even less about bankruptcy.” But by the 1980s, bankruptcy law had shed its “faintly unsavory” reputation to gain prominence in an era that was becoming rife with tactical Chapter 11 filings—from oil-giant Texaco’s bid to stave off a $10 billion jury verdict obtained by its competitor Pennzoil, to TV actress Tia Carrere’s unsuccessful attempt to use bankruptcy proceedings to wriggle out of a contract with General Hospital in search of a bigger payday from The A-Team.

Skeel “found the travails of financially troubled individuals and corporations riveting. It also became clear that American bankruptcy law touches on all aspects of American life.” After graduating from the University of Virginia School of Law in 1987, he began plying the trade for Philadelphia’s Duane, Morris & Heckscher before shifting to academia. In 1999, after eight years at Temple University Law, he joined the faculty at Penn Law, where that year’s graduating class voted to give him the Harvey Levin Award for Excellence in Teaching—the first of several teaching honors including a University-wide Lindback Award in 2004.

Skeel’s scholarship reflected wide-ranging but more or less conventional interests. He published about the controversial rise of Delaware as a bankruptcy venue of choice for corporate debtors. He authored a comparative analysis of corporate governance under bankruptcy proceedings in Germany, Japan, and the United States. He wrote about corporate lockup provisions, sovereign bankruptcy regimes, and the racial dimensions of credit and bankruptcy. (A 2004 paper on the latter subject—which included a fascinating gloss on the “mystifying” absence of “significant bankruptcy practice” in the mid-20th-century lawyering of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander Ed1918 G1919 Gr1921 L’27 Hon’74—was characteristic of Skeel’s nuanced reasoning, keen perception of historical ironies, and measured approach in the suggestion of legal and legislative remedies. Its intricate social and institutional analysis, by a scholar whose politics tend right of center, was also a model for the analytical power of critical race theory before that academic subdiscipline was seized upon as a culture-war cudgel.) His 2005 book Icarus in the Boardroom: The Fundamental Flaws in Corporate America and Where They Came From examined the history of corporate crises from the 19th century to the Enron and WorldCom scandals, and it advocated for a series of focused reforms to protect corporate shareholders, suppliers, and employees from executives who are often incentivized to take “excessive or fraudulent risks.”

It wasn’t until the mid-2000s that an explicit attention to Christianity began to percolate through his prose. One of the first instances came in 2003, after the Archdiocese of Boston hinted at declaring bankruptcy as it faced massive liabilities stemming from hundreds of clergy sexual misconduct cases. In an article for the Boston College Law Review titled “Avoiding Moral Bankruptcy,” Skeel warned against the temptation for the Church to “evade obligations to victims,” but argued for the potential merits of a filing. Chapter 11’s provisions for “pervasive court oversight and extensive scrutiny” could force the archdiocese to reckon with its wrongs—“confirming the Church’s accountability rather than undermining it.”

The next year, Skeel began a critical appreciation of Elizabeth Warren—who at the time was not yet a US Senator but rather “the nation’s leading consumer bankruptcy scholar”—by recounting a “wonderful passage in the New Testament.” The article was otherwise unconcerned with Christianity, but its author seemed to be gaining comfort wearing his own in plain view.

“There came a point,” Skeel reflects, “where I realized that the story of Christianity—the story of the Gospel, as we would put it—and the idea of the fresh start with bankruptcy are very closely parallel. The idea that you’re indebted beyond your ability ever to escape that indebtedness, you can’t get out on your own … it’s almost exactly the same trajectory as the idea of what Jesus is” from an evangelical perspective, which emphasizes that reconciliation with God can come only by embracing Christ as the Savior, not through a believer’s good works.

“And when that occurred to me, I started to see all of the economic language in Christ’s teachings, and just how close that parallel was,” he says. “I mean, the most dramatic example of it in my view is in the Lord’s Prayer, when Christ teaches his disciples to pray, ‘forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors,’” Skeel continues, citing the Gospel of Matthew phrasing favored by many Protestant denominations. “I had always thought of that in spiritual terms—and it is meant, I think, to be understood spiritually. But I also think it’s quite literal, that it’s not accidental that Jesus used so many economic metaphors in his teaching.”

This observation is hardly unique to David Skeel. “Other than sex,” as he put it in a more recent article, “almost no other feature of daily life figures so prominently in Scripture as debt.”

And that was only one aspect of his growing interest in examining the law through the prism of his faith.

The Irony of Moralist Law

A philosophical watershed moment came in 2006, via a paper he coauthored with Harvard Law School professor William Stuntz, an influential and somewhat iconoclastic theorist of criminal law and procedure who died in 2011. “Christianity and the (Modest) Rule of Law,” which appeared in the Journal of Constitutional Law, brought the two scholars’ evangelical Christianity directly to bear on US criminal justice.

Skeel and Stuntz presented the Bible as a seedbed of ideas supporting the classic secular conception of the rule of law: all men and women have dignity in the eyes of God, hence “government should treat even those it punishes” with the “respect due to creatures made in God’s image”—an egalitarian requirement “that is heightened when the government’s wrath is visited on the poor, who are usually the recipients of criminal punishment.” Yet everyone needs to be governed, because all humans are prone to sin. “And since sin is universal and since those who do the governing must themselves be governed, law (not government officials) must do the restraining.”

Observing that “clearly articulated rules” that “punish conduct, and never intent alone” are foundational to the rule of law, the authors emphasized a major threat to it: the individual officials, prosecutors, and regulators empowered to decide who to target for breaking rules. “Discretionary power means the power to oppress,” and the abuse of that power was visible anywhere you looked. “Drug crimes in poor city neighborhoods regularly lead to long prison terms” whereas “upper-class drug crime is treated more generously.” Martha Stewart was just the latest CEO to have been targeted mostly “for being famous and unpopular,” they argued—jailed for “crimes that are committed every day without legal consequence” by people whose convictions wouldn’t land a prosecutor on the front page. Excessive discretion, Skeel and Stuntz contended, sets the stage for discriminatory enforcement—and consequently breeds contempt for the rule of law as a mere “veneer that hides the rule of discretion.”

So how does God’s law measure up to this standard? Horribly, Skeel and Stuntz observed. It’s virtually the opposite. Consider the Golden Rule, which commands that we love our neighbors as we love ourselves. Forget the principle that rules must be defined with reasonable specificity. “One can barely imagine a more vague and open-ended legal requirement.” And it gets worse. Turning to the Sermon on the Mount, the authors noted that Jesus “defines as murderers ‘everyone who is angry with his brother,’” and declares that adulterers include “not only those who have sexual relations with others’ spouses, but ‘everyone who looks at a woman with lustful intent.’

“No legal system that defined murder and adultery as Jesus did could enforce those offenses with any consistency. Such laws would function like highway speed limits—all drivers violate them, so the real law is whatever state troopers decide. And Jesus himself applied God’s law differently to different people,” they continued, “violating the principle that all should be bound by the same rules.”

“God’s law,” Skeel and Stuntz wrote, “violates every single principle that flies under the banner of the ‘rule of law.’ If the state tried to replicate this law in a legal code, police and prosecutors would have total, absolute discretion to choose who should be sent to jail and who should go free; and civil law regulators could pick their least favorite CEO and punish him or her whenever they chose. In practice, the discretionary choices of the governors, rather than God’s law itself, would govern the people.”

And that, they contended, is what tends to happen whenever “legal moralists”—including Biblically inspired ones—gain the upper hand.

At one extreme lies the 18th Amendment, which criminalized the production, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. Zealous enforcement of a prohibition that was opposed by a substantial minority of citizens—and majorities among some ethnic and geographic groups—arguably did more to undermine respect for the rule of law than it did to advance the moral project of the Temperance movement. “The proprietor of an establishment that sold beer in a working-class Irish or Italian neighborhood in New York City might well wind up in jail,” Skeel wrote elsewhere. “[T]hose who sold gin in an upscale, upper East Side neighborhood were far more likely to wind up in an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel.”

At the other end of the spectrum are largely symbolic laws ranging from the 1910 Mann Act, which made it a felony to transport “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose” (emphasis added); to Republican efforts in the mid-2000s, under pressure from conservative Christians, to keep Terri Schiavo alive in a persistent vegetative state by inserting Congress into the private medical decisions of a single family; to various bipartisan spates of redundant “corporate responsibility legislation” in reaction to the business scandal of the moment.

Skeel and Stuntz were equally scathing about that brand of legislative moral posturing. “Members of Congress can please constituents who wish to condemn the relevant conduct, without paying either the fiscal or political price of stopping that conduct. In contrast to legislation that embodies compromises and tradeoffs, federal criminal law is a land of broad ‘thou shalt nots,’ leaving the compromises and tradeoffs for law enforcers.”

God’s law, in short, exemplifies the radical and potentially transformational scope of all good moral principles, which “reach into every nook and cranny of our lives and our thoughts” to stir us to virtue. But its instructive power curdles upon contact with the institutions by which men and women police one another. In a world where “all sin but only some sinners can be punished” and “rulers are prone to favoritism and exploitation,” Skeel and Stuntz wrote, the law must play a “double game: restraining the worst wrongs by the citizenry without empowering judges and prosecutors to do wrong themselves.” This is best accomplished, they contended, by limiting the law’s reach—“draw[ing] lines not between right and wrong, but between the most destructive and verifiable wrongs, and everything else.”

Our secular legal system would do well to learn that “moralist criminal law turns out not to be particularly moral,” they concluded. And “conservative Christians could stand to learn the same lesson.” Not just because Paul the Apostle preached it in the first century, but because converting moral codes into abuse-prone legal ones risks damaging the evangelical project itself. When overweening Christians try to “write morality into the statute books” via campaigns targeting widely tolerated practices like gambling, alcohol, or abortion, they make their faith alien and aggressive toward those they should be seeking to attract—while “distract[ing] religious believers from other, more limited efforts that might command widespread support.” In effect, they yield to the temptation to “turn God’s law into a list of purposeless rules, a kind of Biblical version of the Internal Revenue Code,” reprising the pitfall for which Jesus criticized the Pharisees.

“Conflating God’s law and man’s law,” they declared, “does violence to both. It makes far too much of man’s law, and far too little of God’s.”

The Justice Paradox

In the years since he and Stuntz articulated their Christian case for a minimally ambitious legal code, Skeel has continued to evangelize about the perils of legal moralism and symbolic religious legislation. He devoted a chapter of True Paradox—which was pitched at general readers, not legal scholars—to what he calls the “justice paradox.” It flows from two observations. Humans have long placed remarkable faith in the idea that the right system of law can produce a just social order. Yet from Hammurabi’s Code to Napoleon’s, and from Marxism to the libertarian system of laws inspired by John Stuart Mill, we have been disappointed over and over again.

“Both parts of that pattern—the hubris about our capacity for justice and the failure that follows—are important,” Skeel wrote. The New Testament demonstrates this dynamic twice over, as first the Jewish authorities and then the Roman ones condemn Jesus on suspect grounds. “The hero of the Christian story was murdered by impressive legal systems, not transparently evil ones,” Skeel noted. “Lest we think that it is simply an accident that one system of law failed, the Jesus story shows that even two legal systems working together and potentially correcting one another cannot ensure a just outcome. The justice paradox lies at the very heart of the Christian story.”

Yet it’s hard to read Skeel’s stipulation that “Christians believe … that the legal codes we create to foster morality will always fail” without marveling at just how distant it is from the reigning spirit of the American religious right.

He acknowledges as much. “For many evangelicals and other theologically conservative Christians,” he lamented in one law review article, “the legal system is the solution of first resort for nearly every conceivable issue.”

It bears mention here that theological conservatism frequently overlaps with the political variety, as in the case of Christian sexual ethics. But it can also veer in other directions. Skeel is by no means the first, for instance, to find the Mosaic law “unabashedly paternalistic in its concern for the dignity of the poor.” By the same token, the religious enthusiasms of the political right do not always hold water with theological conservatives. The fervor for so-called “muscular Christianity”—whose manifestations have ranged from early-20th-century missionary excesses to today’s #GodGunsAndCountry crowd—strikes Skeel as being “more about American culture and values than about Christianity and the Bible.” He calls the “prosperity Gospel” of Joel Osteen and Paula White (who chaired President Donald Trump W’68’s evangelical advisory board) “deeply unbiblical” and “very damaging.” Skeel has been a registered Republican for some time, but professes to have a “lover’s quarrel with both parties.” Leery of state power and impatient with culture war, he is “not optimistic about there ever being a party that captures my views in a robust way.”

In his legal scholarship, he has focused most consistently on the pitfalls of moralistic legislation—contending that it not only makes for bad secular law, but often undermines the moral authority and effectiveness of its proponents, especially when they are motivated by religious concerns.

This tendency has periodically animated American Christianity since at least the era of Prohibition, which Skeel condemns in terms that echo the contemporaneous criticism of the Protestant intellectual Reinhold Niebuhr.

“Ideally, laws should be adopted by common consent, so that they would require enforcement only upon that small minority of chaotic souls who are incapable of self-discipline,” Niebuhr wrote in 1928. “Whatever the State may do to secure conformity to its standards, it is hardly the business of the Church, ostensibly committed to the task of creating morally disciplined and dependable character, to use the ‘secular arm’ for accomplishing by violence what it is unable to attain by moral suasion.” Characterizing Prohibition as an effort by a Protestant majority to bring “more recent immigrant groups which are loyal to Latin religious ideals and traditions under the dominion of Puritan ideas by the use of political force,” Niebuhr charged that “it is alien to the true character of religion.

“And its effect upon the nation is permanently schismatic,” Niebuhr emphasized. “Such a degree of animosity has been created by the policy that a mutual exchange of values between the two cultural and religious worlds has become difficult, if not impossible.”

It is perhaps no coincidence that Skeel, writing in another era of national schism, should take up a parallel argument.

“The spirit of Prohibition lives on,” he wrote in True Paradox. “Americans’ confidence in the curative powers of the law has not dimmed a whit. Lawmakers continue to pass laws designed to regulate morality, such as the laws making many forms of gambling (most recently, Internet gambling) illegal, and other laws creating a special category of additional punishment for hate crimes.”

Legislative crusades against vices like gambling, in Skeel’s view, succeed mostly in teaching millions of citizens to ignore laws that lack common consent while driving the targeted activity underground—to be policed, or not, at the whims of beat cops and prosecutors. (They may also lack staying power, as shown by the widening scope of legal gambling in the last several years.)

The religious right’s quest to outlaw abortion, exemplified most recently by a Texas ban that effectively outsources enforcement to self-appointed vigilantes, nettles him for similar reasons. “I am personally pro-life, so I would love to see a society where there’s no abortion,” Skeel says. “But that’s not the society that we live in at the moment. So I’m not a big fan of the Texas law, because I think the law goes way beyond where we are now as a society.

“I am sympathetic to banning late-term abortions, as the Supreme Court allowed a while back,” he adds. “But the idea of completely making abortion illegal, I think, would create social chaos.”

One of the things that distinguishes Skeel’s Christian-inflected legal commentary is its earnest genuflection toward pluralism. Another is his propensity to challenge the assumption that two opposing perspectives are in fact ineluctably at odds with one another—often by complicating debates that have been dumbed down via relentless simplification.

“The deep divide between moralists and libertarians may be needless, the result more of theological error than of spiritual disagreement,” he and Stuntz wrote in their case for modest rule-of-law. “Libertarians seek to minimize formal legal restraints on private conduct. That agenda should hold some appeal for wise moralists, at least if the moralists are Christian. After all, the rule of law is a moral good in Christian terms.” Meanwhile, their critique of prosecutorial overreach has lately found the loudest echo among progressive proponents of criminal-justice reform, including some who have marched under Black Lives Matter banners.

The dangers of symbolic religious legislation are “particularly stark in the current political environment,” Skeel warned in 2008, suggesting that the almost wholesale alignment of evangelical Christians with a single political party “invites strategic extremism” that could come back to haunt their cause. The irony of abortion politics, he observes, is that the side that prevails in the legal realm has a way of losing in the court of public opinion—a hearts-and-minds battle that may matter more. In the 1960s, when abortion was a crime, public sympathy for the plight of women forced to seek black-market procedures drove a successful movement to make it a right. Whereupon the actual rate of abortion, which had risen steeply in the years leading up to Roe v. Wade, soon began a long and lasting decline—sustained in part, one can argue, by the ability of anti-abortion advocates to redirect public attention from the horrors of back-alley abortions (which all but disappeared) toward sympathy for embryos and fetuses. “When the relevant legal territory is morally contested, the law’s weaponry tends to wound those who wield it,” Skeel and Stuntz wrote. “Legal victory produces cultural and political defeat.”

The tenor of much contemporary religious discourse in the United States, where moralism often manifests as self-righteousness and the spirit of self-actualizing individualism suffers no shortage of champions in church pews, leaves a lot to be desired. Popular concepts like prosperity theology and muscular Christianity can seem hard to square with the Lamb of God’s thoroughgoing concern with the poor. Meanwhile, anti-intellectualism is worn as a badge of honor in too many evangelical pulpits—where cultural “victories” are apt to be measured by how easily bakers and florists can deny services to people they condemn as sinners. The consequences of all this can be seen both in the antipathy with which many secularly oriented Americans regard evangelicals, and in the shrinking numbers of evangelicals themselves over the past 15 years.

“Christianity was introduced to America,” as one caustic formulation goes, “and America triumphed.”

Against that backdrop, reading David Skeel is like entering a parallel universe, where theological conservatism never became estranged from the academy, nor so thoroughly entangled with the gospel of American materialism.

Skeel’s mission with True Paradox was to reclaim “complexity” as a central element of his faith. “The assumption that Christianity and complexity don’t mix seems to be shared not just by religious skeptics, but also by many Christians,” he wrote. “Yet it actually gets things precisely backward. Complexity is not an embarrassment for Christianity; it is Christianity’s natural element.”

The book, he says, is “for people who think there’s no reason to take Christianity seriously. It’s to show people of that sort—they surround me in my professional life—that Christianity is much more plausible than they think.”

These days, when David Skeel thinks about the purpose of the law, he increasingly frames it in terms of creating relationships.

“If the dignity that comes from our being made in the image of God requires that we seek one another’s flourishing, as Christians believe it does, one positive contribution that laws can sometimes make is to foster relationships in contexts where they otherwise might not occur,” he writes. He holds up the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as paragons—in no small part because, “unlike many social and moral reforms,” they were not criminal laws. “They were not designed to put offenders in jail or even to impose damages for the wrongs committed against blacks in the past.” Rather, the former sought to give us a more integrated workplace, while the latter aimed to give us an integrated political community in which Black and white citizens can vote side by side.

“The main reason these laws have been so successful,” he concludes, is that they “actually help to create relationships in our communities.”

Reflecting on the long trajectory of his scholarship, he calls that idea “a scattered theme in my writing that I’ve come to see as more and more central. So if you ask me what the objective of a legal system ought to be, my short answer would be that it should be designed to try to foster right relationships within our communities. What that means in a given context is complicated, and it could mean different things. But to me it encompasses seemingly disparate parts of the law.

“I would argue that it’s a goal of our bankruptcy system, as well,” he adds. “People who are overwhelmed by debt are effectively excluded from the community. … It crushes everything else. It interferes with relationships. It complicates a person’s life in a variety of different ways. So a bankruptcy system that works effectively helps with your relationship from a financial perspective.”

Then Skeel zooms back out for the wider view.

“To me, the art of justice is trying to balance freedom and equality, which are often in tension with one another. And to do it in a way that fosters relationships. If someone asked me for my abstract definition of justice, that’s what it would be.”

And there he pauses, an unpredictable scholar and uncommon evangelist, who is so often to be found on the cusp of an idea that repays close attention.