It’s a tough time to be a state. New York governor Andrew Cuomo kicked off the year by declaring a “debt emergency” in the face of an estimated $9 billion budget deficit in 2012. But he’s got it easy—at least compared to Illinois, which is on track to bleed $15 billion in fiscal 2011. And the only bright side for Illinois is that it’s not California, whose projected deficit of up to $25 billion next year has spurred The Wall Street Journal to dub it “the Lindsay Lohan of states.” Altogether, the 50 states face a combined $82 billion in deficits in fiscal 2012, according to the Conference of State Legislatures.

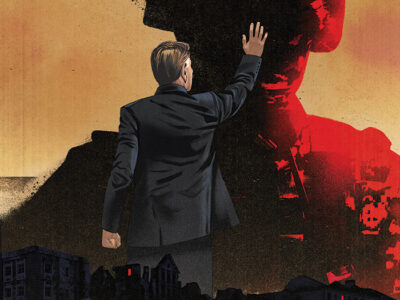

The $82 billion question, then, is: Do the states have sufficient tools to put their fiscal houses in order? David Skeel, the S. Samuel Arscht Professor of Corporate Law, doesn’t think so, and in February he made a trip to Capitol Hill to advocate a solution: allow states to declare bankruptcy. Testifying before the House Subcommittee on TARP, Financial Services and Bailouts of Public and Private Programs, Skeel expanded on an article he wrote for The Weekly Standard in November. “No American state has defaulted since Arkansas during the Great Depression. But it is no longer unthinkable,” he told members of Congress. And default is not the only dire prospect for a state in deep crisis. “The second option is for the federal government to bail out one or more of the states, much as it bailed out financial institutions like Bear Stearns, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and AIG during the recent financial crisis.

“In my view, both of these alternatives are deeply problematic,” he said. “In other contexts, a person or an entity that is in deep financial distress can use bankruptcy to restructure their obligations. I believe that Congress should enact a bankruptcy law for states, to provide a similar option for states as an alternative to a default or a federal bailout in the event that all else fails.”

Gazette associate editor Trey Popp tracked Skeel down by email to ask him some questions about the benefits and drawbacks of letting states declare bankruptcy.

What does a state like Illinois or California stand to gain from declaring bankruptcy?

Hopefully, Illinois and California would never actually need to use the bankruptcy law, if one were enacted. But the law provides several hugely important benefits as an option of last resort. The first is that obligations that are difficult or impossible to restructure outside of bankruptcy may be on the table in bankruptcy. Both pensions and bond debt are extremely difficult to adjust in many states, for instance, but would likely be subject to adjustment in bankruptcy. The second benefit is that bankruptcy ensures the sacrifices are borne by more or all of a state’s constituencies, rather than just one or two.

What about taxpayers who live in fiscally healthy states? Do they stand to benefit from a law that would permit budgetary basket-case states to declare bankruptcy?

They benefit indirectly to the extent a bankruptcy law makes a state’s fiscal crisis more manageable. State bankruptcy also makes it less likely that taxpayers of a fiscally responsible state will be forced to foot the bill for their profligate neighbors, because the federal government is less likely to have to step in.

Why are states currently barred from seeking bankruptcy protection?

Before the modern era, there might have been uncertainty as to whether Congress could constitutionally enact a bankruptcy law for states. But the Supreme Court upheld bankruptcy for municipalities—which are of course subdivisions of the states—in 1938. It seems clear that a bankruptcy law for states that honored state sovereignty in the same ways as the municipal bankruptcy law does would also be constitutional.

So cities and municipalities have been able to file for bankruptcy for 70 years. How many have taken advantage of it, and have the benefits outweighed the drawbacks?

I’m not sure how many have taken advantage. Overall, the number has been small. It’s been a last resort. For a number that were truly in trouble, it has worked out well. Orange County’s bankruptcy in the 1990s is generally seen as a success. Vallejo, California has been in bankruptcy for some time and seems to be making progress, although not painlessly.

States with structural deficits often seem particularly stressed by the pension benefits they owe current and future civil-servant retirees. How threatening do you think state bankruptcy would be to those groups?

I think it’s highly unlikely that existing pensions would be radically restructured. But bankruptcy might provide the ability to do things like restructure not-yet-earned benefits of current employees.

It seems like declaring bankruptcy would be the last thing a governor would ever want to do—especially in a state like California, where governors can be recalled. Is there enough of a political upside to it that a state might actually avail itself of the bankruptcy option?

I do think it would be an absolute last resort. No governor would want to propose it, unless the other options simply weren’t going to be enough.

How punitive should state bankruptcy be? How do you strike the right balance between satisfying a state’s creditors and protecting its citizenry from penury—or at least their fear that state bankruptcy might lead to extortionate tax burdens or the evisceration of social services?

There’s no bright-line answer to this question. A major virtue of bankruptcy is that it brings everyone to the table to hash out these kinds of issues.

Your advocacy of state bankruptcy in The Weekly helped to push this idea to the front of a lot of people’s minds, and Newt Gingrich has been on the same warpath. Care to handicap the likelihood that we’ll see legislation on state bankruptcy from the new Congress?

I think the odds are still long. Many Republicans and most Democrats have not been persuaded yet. But I haven’t given up hope.