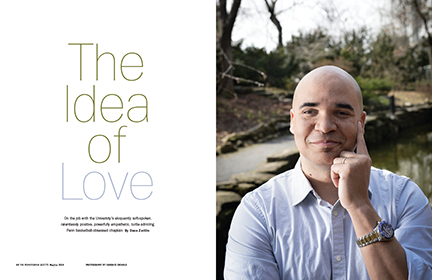

On the job with the University’s eloquently soft-spoken, relentlessly positive, powerfully empathetic, turtle-admiring, Penn basketball-obsessed chaplain.

BY DAVE ZEITLIN | Photography by Candace diCarlo

The Reverend Charles L. “Chaz” Howard C’00 loves turtles. Always has. Every year for his birthday, the University of Pennsylvania Chaplain asks his wife for a baby turtle, but his real dream is to one day own one of those big Galápagos tortoises you see at the zoo. For now, though, he has to settle for keeping a few turtle statuettes on his office bookcase.

“They remind me not to go too fast, to savor life as you go,” Chaz says, his three daughters happily playing on his computer behind him. The four of them had just walked from the Palestra to Houston Hall, scampering upstairs to the empty chaplain’s office on a bitterly cold Saturday afternoon in January. They were coming from a Penn women’s basketball game, one of the only times Chaz allows himself to get too hyped, enthusiastically cheering on the Quakers from his seat behind the basket. Great board! Oooh! Gotta make a run here! Pop it! Buckets! That’s a good call! (“Don’t say, ‘That’s a good call,’” one of his daughters scolds, feigning embarrassment at her dad’s endless positivity, which is sometimes even directed toward the referees). But most of the time, like his favorite reptile, Chaz exudes a sense of calm—an important attribute for his role overseeing and coordinating spiritual and religious activities at Penn.

“I also like that they carry their home on their backs. It’s a reminder of keeping family close,” Chaz adds as he looks over at his girls, who are currently trying to come up with a name for the new betta fish (a fine turtle substitute) he recently bought for his office. (Some of the top choices: Cleo, Larry, Bruce, Bubbles, Sushi, Flash, Ursula, and Swimmy.) Chaz enjoys having his three daughters—whose middle names are “Faith,” “Hope” and “Love”—visit him at his office, which four years ago moved from the Penn Women’s Center building on Locust Walk to a larger space on the second floor of Houston Hall. (Before that, the chaplain’s office was jammed into what is now a package room in the Quadrangle.)

In many ways, his love of family and Penn is intertwined. Chaz met his wife, Lia Howard C’00 Gr’10, when both were undergraduates, falling hard for the smartest and most warmhearted person he knows, even if they’re opposites in a lot of ways. “I’m this 6-foot-2 black guy from Baltimore; she’s a 4-foot-11 white Italian from California by way of Philly,” he says. “I think I trend lethargic at times; she’s a high-energy, life-of-the-party, wide-eyed, third-cup-of-coffee-by-11 kind of person.” (Lia Howard has taught political science at Penn and St. Joseph’s University and is currently the executive director of the Agora Institute for Civic Virtue and the Public Good and professor of political science and liberal studies at the Templeton Honors College at Eastern University.)

Lia and Chaz were married in Houston Hall’s Hall of Flags; he passes through where the reception was held every day on his way to work. His two oldest daughters were born around the corner at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. And the whole Howard clan spends so much time on campus, he has a feeling his daughters might not want to attend college at their parents’ alma mater. Which is fine of course—with only one exception. “Anywhere but Princeton,” he says with a smile.

A playful jab at Penn’s traditional archrival might be the meanest thing you’ll ever hear come out of his mouth. If you’ve attended Penn over the last decade, you’ve almost certainly heard his message of love, hope, positivity, and inclusion. Chaz’s soothing, baritone voice is, quite literally, the first and the last one that Penn students hear, his opening remarks at Freshman Convocation and closing remarks at Commencement serving as inspirational bookends to a college journey. But for Chaz—a naturally introverted person who needs to retreat to his office and pull the shades down after speaking at ceremonial occasions—it’s all of the one-on-one talks with students in between that makes his job so rewarding. That’s when he’s truly in his element: listening, learning, laughing, loving, lending warmth. “He just has a way,” says the chaplain’s office manager Mary O’Rourke LeCates, “of hugging you without hugging you.” Or, as his predecessor, Reverend William Gipson, puts it: “He has a very gentle and powerful presence simultaneously.”

Chaz is in his 10th year as Penn’s chaplain, and at no time in his tenure have these counseling sessions felt as imperative as they are now. In large part due to what he calls a “super-charged political atmosphere,” he’s noticed an uptick of people who want to talk, particularly minority students who are trying to cope with stress beyond the typical classroom anxieties. It’s also been an “unusually hard” academic year with seven students passing away by mid-February, including the high-profile deaths of freshman William Steinberg (who died in a plane crash while vacationing with his family in Costa Rica on New Year’s Eve day) and sophomore Blaze Bernstein (who was murdered while home in California during Winter Break).

When a student dies, part of Chaz’s job is calling the parents to “tell them their greatest fear has come true,” before then planning and presiding over campus memorials. He also deals with the “secondary trauma” of their classmates grappling with life and death. There’s no easy way to have those conversations. But he always tries to preach a message that revolves “around home, around love, around taking care of yourself, around seasons changing, around the future being bright.”

“Here’s what I admire most about Chaz: Whenever something or someone threatens to get our community down, Chaz rises to the occasion and acts on the conviction, which I hold dear, that to save a life is to save an entire world,” says Penn President Amy Gutmann. “He saves Penn lives by offering hope, love, and support to our amazing—yet also vulnerable—students, and he does so one precious life at a time. There’s no counting the times when Chaz has joined me—and everyone else on the Penn team—to minister hope, love, and support to Penn students, parents, friends, and myriad members of our broader community.”

And his door is always open for anyone to come in, no matter their religious beliefs (or lack thereof), to escape the daily grind and find a few minutes to reflect.

“In a world that’s rushed, on a campus where the pace is really high and intense,” says Penn’s associate chaplain, Steve Kocher LPS’13, “I think he exemplifies taking time to focus on the things that really matter, taking the time to have a conversation, to pause for a breath.”

Just like the turtles.

True Calling

Chaz Howard never expected to be the person helping guide Penn students on their path, not when his own path as an undergraduate was filled with so many potholes. In fact, his road to graduation almost disappeared entirely when, during the second semester of his junior year, he received a letter that made his heart sink. “The bottom kind of fell out from me in life,” he says softly. “I got kicked out of school. Grades.”

Grades may have been the reason, but drinking was the cause. At the root was a mix more potent than any cocktail: coping with the deaths of his parents while overextending himself on campus. Chaz had just been elected head of the Sphinx Senior Society; he was the chair of the United Minorities Council (UMC); he sang a capella; he was a leader in Penn’s chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, an African American fraternity. It was all too much. “I was waking up tired, unable to go class, self-medicating with alcohol to get over grief and sadness,” he says.

As he drank, he thought about how his father died during the first semester of his freshman year, just after his arrival at Penn from his hometown of Baltimore. And how his mom had died when he was 11, literally in his arms, when she awoke in the middle of the night feeling very sick from a heart condition probably developed from years of smoking. And how, after his mother’s death, he lived with his half-sister, Amy, who was 12 years his elder and helped raise him—which included dropping him off at church on Sundays.

But while God and prayer and scripture were always important to Chaz, he never saw himself as a “church guy” and never imagined becoming a man of the cloth. Throughout most of his time at Penn, he had plans to use his urban studies degree toward a career in politics. It wasn’t until getting kicked out of school that he felt an “overwhelming draw” to become a minister. He started having dreams about it. He told friends about it too.

One of those friends was Andrew Exum C’00, who went on to fight in two wars with the US Army [“A Dark Task,” Jul|Aug 2004] and serve as deputy assistant secretary of defense for middle east policy during the Obama administration. Long before that, the two of them were sitting at Smokey Joe’s one night the summer after their junior year when Chaz announced, “Yeah, man, I think I’m getting called into ministry.” Exum looked down at the six Coronas on the table, then up at Chaz, and deadpanned, “Doesn’t look like it.” That was in August of 1999 and Chaz hasn’t had a sip of alcohol since.

That summer, thanks to the support of then-chaplain William Gipson and other faculty members, Chaz was also allowed to retake a couple of finals and rewrite a few papers to get his grades up enough to remain in school, meaning he never actually missed any time. And he boosted his GPA even more as a senior, which allowed him to not only graduate on schedule but get into grad school at Andover Newton Theological School in Massachusetts. He sobbed the entire walk down to receive his diploma, thinking about his friends, his family, and all the people at Penn who remained in his corner when times were tough.

“Chaz was the student who checked in on the chaplain to see if the chaplain was doing well,” says Gipson, who first met Chaz as a freshman, the two men over six feet tall struggling to talk without bumping legs in the cramped old chaplain’s office in the Quad. “When he went through his rough patch, he came to me and we talked, and I and the other administrators did what we thought was important to make sure Penn didn’t lose this extraordinary young man. And the fact that he was transparent in what was happening in his own life went a long way in our ability to be able to help him.”

In part due to getting “so much love as a student here,” and also because his future wife was in graduate school at Penn, Chaz returned to Philadelphia after receiving a master of divinity from Andover in 2003. Just two years later, while working toward a doctorate at Lutheran Theological Seminary and administering last rites as a hospice minister at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania—“Amongst the most sacred work I’ve ever done,” he says—he was hired by his alma mater to be associate chaplain, working under Reverend Gipson, “a father figure” who had co-officiated his wedding.

Still, Chaz never thought he’d remain in the field of university chaplaincy very long; it was not the model of ministry he imagined during his studies. But then he had another dream. He was at a market, trying on different shirts, none of which fit. Someone handed him a shirt with a Gye Nyame symbol on it, which means “None but God,” and told him, “You’re going to be the next chaplain at Penn.” Chaz woke up, and that same day Gipson pulled him into his office, closed the door, and told him he was leaving his post after 12 years to become the University’s associate vice provost for equity and access, a job he still holds today.

A national search was held for Penn’s new chaplain and Chaz, who despite being younger than 30 and “under-qualified” in his own mind, was named Gipson’s successor in the summer of 2008. Less than a decade after almost getting kicked out of Penn, Chaz Howard had become that same university’s chaplain—a remarkable comeback story he shares with students, especially when any of them are worried about grades.

“It felt like a calling,” he says. “It didn’t feel like just a good job. It felt like I was being called to be here.”

Everybody’s Welcome

As members of the Penn Religious Communities Council convene at the Penn Newman Center in mid-February, Chaz Howard takes a seat at the middle of the table, rather than the head, and sits hunched over. He opens the monthly meeting with a few remarks but speaks sparingly—and quietly, as he’s prone to do—over the course of the next two hours, instead deferring to the invited speaker, James Pawelski, director of education and senior scholar in Penn’s Positive Pychology Center and adjunct associate professor of religious studies.

When Pawelski jokes that he jumped at the opportunity to “come sit with 20 Chazes at once,” everyone laughs. And when one woman responds, “No, there’s only one Chaz!” the chaplain squirms a bit. He might be the de facto leader of the Penn Religious Communities Council—which is composed of the various religious institutions and organizations at the University and runs under the auspices of the chaplain’s office—but he doesn’t see himself as such. What he really wants to do is to prop up student groups like the Muslim Student Association (MSA), the Hindu Jain Association (HJA), Penn Hillel, and PRISM (Programs in Religion, Interfaith, and Spirituality Matters, which Chaz helped start as an undergrad) as much as he can without getting in their way. That’s been one of his main priorities since he became chaplain 10 years ago, and it’s something Gipson also tried to implement after taking over for the Reverend Stanley E. Johnson G’51, who functioned as more of a campus pastor as Penn’s chaplain from 1961 to 1995.

“Will did so much to modernize the chaplaincy. Before him, Stanley Johnson did so much to raise the credibility of the chaplaincy here,” Chaz says. “I wanted to push into what Penn is now: an extraordinary cosmopolitan global campus with a religious life that reflects that.”

Steve Kocher, who’s been Chaz’s associate for the last 10 years, works closely with many of the student groups. He also holds interfaith discussions in the chaplain’s office and gives space for different religious groups to pray or meditate. Some students just come there to study. Others may watch Champions League soccer.

“This space has become home for certain students,” says Kocher, who takes pride in the religious diversity he sees on campus. So does Chaz, who, while sitting on a bench on campus one day, gestures to a very small pocket of Locust Walk and guesses: “Just right here, every major religion is represented.”

One reason for so much diversity, they believe, is the University’s history as a non-sectarian institution that admitted Jewish students, Catholic students, and international students with varying religious backgrounds when others did not. The Office of the Chaplain wasn’t established until 1932—after the Newman Center, the Christian Association, and a predecessor to Penn Hillel already existed.

“I think it’s given us a bit of a sense that everybody’s welcome,” says Kocher, who estimates that about a third of Penn undergraduates are involved with religious life on campus in some way. “Penn has a long history of students from different religious traditions being welcomed.”

During the discussion at the Penn Religious Communities Council, Pawelski posed a thought experiment for the group: In a world with two kinds of superheroes, those who wear red capes and those who wear green capes, what color would you choose? The red cape, he said, lets you look for problems in the world to fix, while the green cape sets you on a path to seek out opportunities to make the world a better place. In other words, if you could only inject goodwill or eradicate the bad, what would you do?

Going around the table, people had articulate reasons for why they’d want to choose each. But when it was Chaz’s turn, he spoke more of what he needed to do than what he wanted to do. In a normal time, he said he’d love to wear a green cape and follow through on some of the cool ideas he comes up with every summer. But the reality is that over the last several years, as Penn has been “bombarded” with an “overwhelm” of crises, from suicides to hate speech to vigils, he feels like he has no choice but to don a red cape.

When Chaz is asked about this thought experiment after the meeting, he adds one thing. Perhaps the chaplain’s office is simply better at responding to crises, he says, than it is at looking ahead and planning the kind of community service events Chaz spent a good chunk of his life focused on. (Among his accomplishments in that space was cofounding the Greater Love Movement, an anti-poverty organization focused on the needs of the homeless). And if that’s true, is there anything wrong with that? Does it feel like an excuse not to have the bandwidth to do both? Chaz ponders all of this for a moment, taking some time to gather his next thought.

“I don’t know, man. I’m more X-Men,” the self-admitted comic book nerd says with a laugh. “They don’t really wear capes.”

Home Is Where the Heart Is

Over the course of one hour on an unseasonably warm February afternoon on Locust Walk, Chaz is approached by no fewer than five people, ranging from a player on the men’s basketball team to someone he once taught to a work-study freshman in the chaplain’s office who doubles as his children’s babysitter. They all treat him like he’s their best friend. “If you try to walk up Locust Walk with Chaz, it’s gonna take twice as long,” Kocher says. “Everyone stops to talk to him.”

You could make the case, then, that there are few people who understand the pulse of Penn’s campus better than the omnipresent chaplain. And even though he spends most of his day talking with students who might not be in the best emotional state, Chaz is inspired by how plugged in and eager to fight for real-world change many of today’s college students are. “I think the optimism and hope among young people that the world will be a better place is here,” he says. “That doesn’t mean there isn’t the moment-to-moment stress of midterms coming up or a big game coming up or will I get a bid for a fraternity or sorority? That’s real. But overall, I think Penn is a hopeful place.”

Chaz also marvels at the range and complexity of today’s Penn students. He and Kocher say they can get whiplash going from a conversation with an international student worried about the effects of President Donald Trump W’68’s executive order travel ban to someone trying to get over a breakup to an African American student traumatized by watching police brutality on their screen to someone else talking about Spring Fling. But it’s not uncommon for many of those subjects to come up over the course of one session. “Kids who have undocumented parents also want to talk about pledging a sorority in the same conversation,” Chaz says. “There’s no hypocrisy. They’re complex.”

While many recent conversations have stemmed from the uncertainty and fear certain people have following the 2016 presidential election—as one example, Chaz spent a lot of time talking with leaders of the MSA about how to respond to the travel ban that targeted Muslim-majority countries—Chaz doesn’t mean to close off relationships with anyone who supports the president. That said, he believes the “lack of care for the individual experience of humans is so mean-spirited coming from this government” that “how can we not speak out?” For him, though, speaking out mostly means trying to help people hurting find the good rather than drowning in the bad.

That goes for anybody who steps into his office—and not just students. Staff and colleagues seek him out when faced with potential illness, or in less dire circumstances, when they’re thinking about their career trajectory or applying for other positions. “Faculty get a lot of religion when they’re up for tenure,” Chaz quips.

People find the chaplain’s office in a variety of ways. Some are referred by friends. Others might be getting crepes on the first floor of Houston Hall and see the sign. Many are not personally religious but curious about the philosophical or existential nature of faith. Sometimes, the Office of Student Conduct (OSC) will send a student who got busted for an illegal download or something similar to see Chaz, who reassures them, “It’s gonna be OK, you’re not gonna go to jail.” Occasionally, Chaz will sense a student doesn’t want to be there. “But most people, I think, by the end of the conversation, appreciate having someone who cares, and someone who listens and who will love them regardless.”

It isn’t always easy for Chaz, and sometimes he needs a release. He has a therapist that he sees because “people dump so much on me every single day, and I’m thankful to be here for that. But I need someone to dump on. So I kind of carry my bucket of tears to her and pour them out for her.” He and Kocher also want to make clear that they’re not exactly therapists or counselors themselves, and will refer people to Student Intervention Services (SIS) or Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) when needed. Chaz also likes to spend time diving into his writing, whether it’s preparing remarks for Penn trustee meetings, penning opinion pieces for national outlets like The Huffington Post, or authoring his book Pond River Ocean Rain (which features Penn’s BioBond, a tranquil place where he likes to sit and reflect). And he enjoys teaching a course in the Graduate School of Education called “Cross Cultural Education” and the undergraduate course “Black History at Penn,” even if he’ll occasionally see someone dozing off due to his soft voice and low-key style.

But he estimates about three-quarters of his day is spent individually with students, sometimes even more during the first few weeks of the second semester when the weather is dreary, the days are shorter, and the stress of finding a job or internship is ratcheted up. And the students really respond to him. “I think it’s because he is so warm and welcoming—and it’s authentic,” says Gipson, echoing a point made by others who know him well. Adds Leah Popowich C’00 G’06, President Gutmann’s deputy chief of staff and a former classmate of Chaz’s: “He has a terrific sense of humor that helps put people at ease … And you’re just mesmerized by his voice.”

His popularity among students could also be because he might not be like some of the stiffer religious figures of their past. He can be self-deprecating. He loves hip-hop music. He said in a TEDxPenn talk that he grew up wanting to be a backup dancer for Janet Jackson or Paula Abdul. He quotes Mean Girls with his daughters. He ran to the theater to see Black Panther several times. He’s such a hoops junkie that he’s told Penn men’s basketball coach Steve Donahue that the only other job he’d want on campus is to be one of his assistants. He has tattoos. “I joke I have Penn on my butt,” he says. “I don’t—yet.”

He’s not the only one shedding stereotypes. According to Chaz, “chaplaincy is much more colorful” and “religiously and ethnically diverse” than it used to be.” For him, being Christian is very important in his life but he also “can’t help but be moved” by other traditions. That’s why his job overseeing all faiths, while getting to meet new people from all kinds of different backgrounds, is a perfect fit. And Penn is also the perfect place for him to do it. “I can’t really imagine doing this work at another school,” he says, “because so much of the fuel for it is giving back to a place that gave me a lot.”

There’s more to it than that, though. Back when he worked in a chaplaincy internship at HUP, he remembers a lot of awkward silences when he first introduced himself to patients. Unsure how to break through, he had an important conversation with his mentor, Ralph Ciampa, who told him, “Charles, when you stay with people, you can go to some amazing places.” Later, in his first year as Penn’s associate chaplain, he noticed someone “mean-mugging” him during a service project. After approaching him to ask what the problem was, the man said, “Look, you’re probably gonna leave here too, just like everyone else leaves.”

“That kind of haunted me—the importance of staying,” Chaz says. “I’ve never stayed at Penn because of guilt. I think I’ve stayed because of love.”

It may sound simple but the idea of love, above all else, has been his guiding principle during his first 10 years as the University’s chaplain. And it will continue to be the driving force for him for the next decade and beyond — all of which, he hopes, will be at his alma mater.

“Twenty-two years [after first getting to Penn] and 10 years into this position, man, we’ve gone to some amazing places,” he says. “And I’m grateful. I love it.

“It’s home,” he adds, a little more quietly. “It’s home.”

Dave Zeitlin C’03 writes frequently for the Gazette.