The new National Constitution Center is billed as a museum of ideas rather than artifacts—but it might have remained just an idea if not for alumnus Joe Torsella.

By Kathryn Levy Feldman | Photography by Candace diCarlo

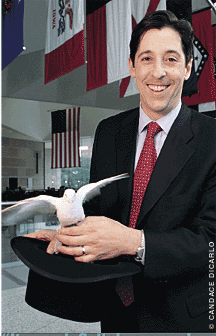

When Joe Torsella C’86 was 12 years old he wanted to be a magician. The budding Houdini studied books, enrolled in professional organizations, and saved his allowance to buy props—developing what he calls “a good little gig” that was also fairly profitable. “I still have the business cards: Joseph M. Torsella: Magic For All Occasions,” he chuckles. “To be honest, there wasn’t much competition in Berwick,” the small town in north-central Pennsylvania’s rural Columbia County where he grew up. The young Torsella entertained at birthday parties, church suppers, Rotary Club meetings and, at one point, (“to show you how obsessive I got,” he smiles) raised his own doves in the basement. “It was definitely a crowd pleaser when I produced fluttering doves from silk hankies,” he reminisces proudly. “And that,” he is quick to clarify, “is actually a trick of skill, not of props.”

This past July, the charismatic 39-year old pulled off a considerably more amazing trick—also a matter of skill—when he made what he calls “a museum of ideas” appear on Independence Mall in Philadelphia.

As president and CEO of the National Constitution Center (NCC)—a $185 million, 160,000 square foot interactive museum and landmark—Torsella has spent the past seven years bringing what had been a moribund project to vibrant life. Writing in The New York Times, Witold Rybczynski, the Martin and Margy Meyerson Professor of Urbanism at Penn, deemed the Center “destined to take its place among the nation’s leading public monuments.”

(There was a little prop-trouble at the opening day ceremonies on July 4, though. A wooden arch framing the stage fell when dignitaries pulled ribbons to officially open the museum. It missed Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who was there to speak and receive an award, but injured a couple of others, including Philadelphia Mayor John Street, whose arm was hurt, and Torsella, who was hit on the head.)

The saga of the Constitution Center begins in 1988, when Congress passed the Constitution Heritage Act, directing the creation, in Philadelphia, of a “nonpartisan, nonprofit organization … to increase awareness and understanding of the Constitution.” But most of a decade passed with little concrete progress. When Torsella took the reins, in January 1997, the project was, as then-Philadelphia Mayor Edward G. Rendell C’65 Hon’00 says, “floundering.”

Under Torsella’s leadership, the Center restructured its finances and operations; recruited a team of scholarly advisers that included Supreme Court Justices O’Connor, Stephen Breyer, and Antonin Scalia, as well as Penn history professor and former College dean Richard R. Beeman (who served as vice chair); selected and hired world-class designers for the building and exhibits (Henry Cobb of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners and Ralph Appelbaum of Ralph Appelbaum Associates, respectively), built nationally recognized programming for students and adults; forged partnerships with institutions ranging from the National Park Service to local hotels and restaurants, and, prop mishaps notwithstanding, opened on time and on budget on July 4, 2003, with a talented staff, polished operations, and a healthy operating endowment in place.

Like the trick with the doves, it was a crowd pleaser.

Besides his magic act, as a boy Torsella occupied himself with projects such as starting a turtle farm in the backyard, damming the creek to make a pond, catching snakes, and doing volunteer work for the yearly Kiwanis Club auctions (“I was made an honorary member,” he boasts). It was, he says, “ a wonderful, bucolic, Norman Rockwell childhood.” A devout Roman Catholic who once considered entering the priesthood, Torsella attended parochial school and then Wyoming Seminary, a “great” prep school 50 minutes from his home in Berwick.

When it came time for college, he wanted to go somewhere “other than Berwick” that “didn’t feel like Las Vegas.” His parents—the late Joseph P. Torsella, a lawyer, and Patricia Balanda Torsella Nu’61 GNu’81, a retired nursing instructor at Bloomsburg State University—had met while they were both in college, his mother at Penn and his father at Temple and then Temple Law, and had fond memories of the city. Torsella remembers yearly pilgrimages to the old John Wanamaker’s department store for the Christmas show and occasional drives into South Philadelphia for dinner. “I loved the idea of school in a city, and when I visited Penn I fell in love with it,” he says.

Torsella majored in history and economics, and channeled his performing urge into Mask & Wig for two years, then shifted gears into public policy. “Somebody said politics is show business for ugly people,” he says with a smile. “So I’m wondering if that’s the thread of my career.”

Torsella threw himself into local politics. In what would have been the fall of his junior year, he left school to work on Wilson Goode’s campaign for mayor in 1983 and Walter Phillips’ for attorney general in 1984. After Goode won, he was named a staff member of the Mayor’s Commission on Literacy under Marciene Mattelman, its founder.

That was also when he met Ed Rendell, then the city’s district attorney. He liked what he saw and later worked for Rendell’s ill-fated 1986 campaign for governor. “The one no one talks about,” Torsella jokes. He was so dedicated to the Rendell cause that he skipped his graduation because it was two days before the primary election. He assumed no one noticed his absence, until a friend told him that, during the ceremony, he’d been called on “to stand up as Penn’s third Rhodes Scholar.” Torsella winces at the memory. “In retrospect, I wish I’d been a little less Type A.”

After three years at Oxford, Torsella returned to Penn, planning to complete a Ph.D. in American history. His thesis was about the British army in the American Revolution, telling the history of the war from the perspective of the British soldier. Then, “One day it hits me—I’m writing this Ph.D. thesis, and the one thing I’m sure I never want to do in my life is teach history,” he recalls. “I love history and, arguably, that is what I’ve done, but I knew I didn’t want to be an academic historian.”

Luckily, at about the same time, Rendell—who had suffered losing campaigns for governor and mayor, and was then working at a law firm and “deeply unhappy,” says Torsella—was mounting the campaign that would lead to two successful terms in City Hall and national headlines as “America’s Mayor.” When Rendell, with whom he had stayed in touch, offered him the position of issues director, “I jumped at it,” Torsella says, deferring and then turning down his acceptance to Harvard Law School, where he had applied after realizing he didn’t want to be a history professor.

“That was such a campaign of substance and ideas,” he says. “How do you re-invent government? How do you deliver services less expensively? Everyone wrote the city off, and we produced paper after paper full of ideas about how to bring it back. It was the way a campaign should be, and it was an energizing moment to be involved with politics and government.”

After Rendell’s inauguration in 1992, Torsella, then 28, joined the administration as deputy mayor for policy and planning. “It was a great time to be part of government,” Torsella says. “We had this great little think-tank institution in municipal government. It felt like a time of great possibility, when you got people to believe in the city again.”

After two years in government, Torsella embarked on his “entrepreneurial phase.” He and a partner did some property development, and he invented, among other things, the Spaghetti Smock, a red-and-white checked bib, packaged in a spaghetti box. QVC sold 1,291 of them in less than three minutes. “I even got—God bless him—Ed Rendell to pose with one.” Torsella laughs. “I think he still regrets that.” He also co-developed the Little Book of Blessings, published by Philadelphia-based Running Press. “The idea is that you keep [it] on your kitchen table and, with your kids, every night you read a different blessing from a different tradition,” he explains. “My kids love the ice cream blessing from Britain.” Torsella is married to Carolyn Short, an attorney. They have two children, and she has two children from a prior marriage, the oldest of whom is a freshman at Penn.

Torsella might still be dreaming up new products (“I have a lot of ideas rolling around in my head,” he says unapologetically), if Rendell hadn’t picked up the telephone in the winter of 1996 and asked him to oversee the proposed National Constitution Center, the board of which Rendell himself had recently agreed to chair. That Rendell had taken this step—chairing a non-profit is “a liability no politician needs,” says Torsella—demonstrated “a huge amount of courage” and made it very difficult to say no. “I remember asking how long he thought it would take,” he says. “‘A day or two a week for three months’ is what he told me.”

It took seven years.

“I kept moving back my departure date,” Torsella explains. At first it was until “the finances turned around,” then it was “until we selected the architect,” then it was “until we got the plans in place.” The truth was that, early on, Torsella was hooked on the Constitution and its most crucial idea—the vision of popular sovereignty captured in the phrase, We the People.

The challenge, as he saw it, was to create an interactive experience where visitors would learn the story of the Constitution’s past, experience the power of its present, and leave empowered to help participate in its future. “The way I’ve always thought of the National Constitution Center is a place where you go and enter as a visitor but leave as a citizen,” he says. “The idea captured my heart in a way I never knew it would. I wish my father were still alive so I could tell him that I finally got a job that made use of my history degree.”

According to John C. Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group and founding trustee and chairman of the NCC, the idea for a Constitution center actually dates back to September 18, 1886, “barely a year before the Constitution’s centennial” when it was proposed by a “Convention of the Governors of the Thirteen States,” who were meeting in Philadelphia. They determined that on the occasion of the Constitution’s centennial in 1887, “A major oration should be read, a commemorative poem commissioned, there should be military and industrial displays, and that a ‘permanent memorial to the Constitution should be erected in Philadelphia.’”

The centennial was celebrated with a parade and a few speeches—but no memorial. It wasn’t until 1982—Philadelphia’s 300th anniversary—that the idea was revived, in conjunction with the bicentennial of the Constitution in 1987. The first board for the National Constitution Center was formed that year, and the following year Congress passed the Constitution Heritage Act—which, however, did not decree what the Center should look like or contain. The board argued over whether it should be a sober and scholarly attraction or should take a more popular approach and bring the Constitution to life for all citizens. Board members came and went; fundraising was extremely challenging; progress was “glacial,” Bogle recalls.

That changed with the entrance of Rendell and Torsella. “The excitement, enthusiasm, and determination they brought to the boardroom was almost palpable,” he says. Within months, the National Park Service agreed to build the Center at the north end of Independence Mall, directly facing Independence Hall; Henry Cobb, whose portfolio includes the U.S. Courthouse in Boston and Commerce Square in Philadelphia, and Ralph Appelbaum, who designed the exhibits for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington as well as the Newseum in Arlington, Virginia, were selected to create an interactive museum to tell the story of We the People, and donors began stepping forward. By the time President Clinton presided over the groundbreaking on September 17, 2000, the state had released more than $22 million in capital funding, the single largest state commitment to any Philadelphia-based cultural institution.

Not that there weren’t bumps along the way. Torsella never doubted that the Constitution Center would get built (“The idea is so, as Jefferson would have said, ‘self-evident,’” he quips), but did sometimes wonder whether it would happen on his watch. By far, the worst of these moments came early on during a U.S. Senate field hearing when the National Park Service unexpectedly “ripped our plans,” Torsella recalls. “Ed and I both felt like we’d been hit in public by a two-by-four across the head, from behind.” (“I now know exactly what that feels like,” he notes, ruefully.)

With their federal subsidy in jeopardy, Torsella and Rendell regrouped that night with Pennsylvania’s U.S. senators, Arlen Specter and Rick Santorum, both of whom, he says “were rocks,” and emerged determined to see the project through. “Ed and I had a conversation during which we said, come hell or high water, there is going to come a day when we are going to walk through the doors of the National Constitution Center,” Torsella recalls. “I definitely discovered something about belief and persuasion. The crucial step is imagining and believing the possibility. Once you commit to that, other people commit, too.”

When all was said and done, $85 million in combined state and federal funds was allotted to the Center, with the city contributing $5 million and the Delaware Port Authority putting in $10.5 million. Substantial gifts came from the Annenberg Foundation ($10 million to establish the Annenberg Center for Education and Outreach, the Center’s educational arm) and a number of other individuals and foundations. “That we [went] into the homestretch with $175 million in hand is a remarkable tribute to Torsella and the outstanding staff he has built,” comments Bogle.

Laura Linton, executive vice president of the NCC, has worked closely with her boss through most of the planning and implementation phase. “Joe was the driving force and supplied the vision with regard to raising the funds, managing the budget, building the staff, and the design and content of the exhibits,” she says. “He is one of the smartest people I have ever known, but he also has a sense of the practical that many visionaries lack.”

Bogle calls working with Torsella “one of the most rewarding experiences” of his life. And the governor of Pennsylvania is equally effusive: “The best thing I ever did for the NCC was to put Joe Torsella in charge of it,” remarks Rendell. “Without Joe, the Center would not be open and would not be what I believe it is today —the best new museum in America and a stunning national landmark.”

What makes it so, in Torsella’s view, is its cohesiveness. The building itself, rather than echoing the surrounding historic structures, is intentionally contemporary, reflecting the fact that “the Constitution is not a historic artifact but a document vital to our lives today,” Torsella says. It is made of limestone, giving it “the texture of American civic institutions such as post offices, schools, banks, libraries,” and features large windows designed to make it appear transparent, displaying “activity and movement—the very civic life enabled by the Constitution,” he adds. “The words of the Preamble are writ large on the façade of the building.” From the moment visitors enter the Center and are issued “Delegate’s Passes” (with instructions to think of themselves as “Founders”), they become part of the ongoing conversation about the nature of the American experiment in self-government. “Democracy is not a spectator sport,” says Torsella. “The story is actually about you.”

The first part of the dialogue takes place in the 350-seat, steeply sloped Kimmel Theater, site of a dramatic and effective 17-minute multi-media orientation presentation, Freedom Rising. An actor strides to the middle of the auditorium and asks, “What makes us Americans?” The story of the Constitution, foibles and all, is projected alternately on the floor, on the 360-degree screen around the perimeter, on a scrim that fills the center of the space, and, at key points, on the audience themselves. The presentation ends as it begins, with a question: “What will we do with freedom?”

From there, the visitor exits to the second-floor gallery space. While the displays include artifacts in glass cases (notably the inkwell Abraham Lincoln used to sign the Emancipation Proclamation, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s leg braces, a signed copy of the sheet music for Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” and the tool bag used by the Watergate burglars), this is a museum about ideas, not artifacts. Ralph Appelbaum has created interactive multimedia exhibits such as the American National Tree, from which visitors choose to hear and see the stories of 100 significant Americans, from Mickey Mouse to Muhammad Ali. They can also enter such “immersive environments” as a recreation of a 1940s living room with one of Roosevelt’s fireside chats playing on the radio, take the presidential oath of office on the steps of the Capitol (and purchase a photo of the historic event from the gift shop), try on a robe and sit on a replica of the Supreme Court Bench, and vote for their favorite president of all time. Rybczynski calls the information “deeply layered, designed to engage teenagers and children as well as adults,” and while the sheer volume of material can be overwhelming, it is never intimidating. “The idea is that if you come here with a kid who’s not interested at all and a wife who’s a Constitutional lawyer, there’s something for both of them,” he says.

From the gallery, visitors enter Signers Hall, a stylized evocation of the Assembly Room in Independence Hall where the Constitution was drafted, complete with 42 bronze life-size statues of the 39 men who signed the document and the three who refused. Visitors are asked to make the same choices the Framers faced: sign or abstain. Those who sign actively affirm the principles of citizenship; those who dissent are asked to state their reasons. Plans are to store the custom-made volumes of signatures, in perpetuity, on shelves around the room.

Leaving Signer’s hall, one enters the Citizens Café, which offers a breathtaking view of Independence Hall. “It is hard not to be moved by this evocative view of its graceful Colonial spire against the crowded backdrop of downtown office buildings,” comments Rybczynski.

One million visitors are projected to tour the Center annually; according to Torsella, they are averaging about 80,000 per month. More than sheer numbers, the greater goal is that the visitor experience will, in time, change the civic behavior of those who made the trip. Torsella acknowledges that this is a “high standard by which to judge the ultimate success of a museum,” but, he feels, an appropriate one. “Constitutional scholar Garrett Epps said, ‘No legal document is self-validating,’” he quotes. “Every morning we wake up and decide we want to live in a constitutional republic.”

In September, Torsella announced that he would leave the Constitution Center at the end of the year in order to run for office himself. This April, he will compete in the Democratic primary for U.S. Representative for the 13th Congressional District, which includes parts of Northeast Philadelphia and Montgomery County. It is perhaps only natural that after seven years of steeping himself in Constitutional doctrine and “talking the talk,” Torsella would decide to “walk the walk” and enter the political arena. But leaving the NCC is bittersweet, he says. ”This has been a very difficult decision because this place will always feel like home, and the people I have worked with will always feel like family,” he says. “I am prouder than I could ever say to have been part of creating this remarkable place.”

Kathryn Levy Feldman is a freelance writer and Penn parent. Her most recent article for the Gazette was on the Senior Associates program, for retirees who wish to audit classes at Penn, published in the January/February issue.