Penn’s Morris Arboretum owes much of its botanical diversity to the work of plant hunters, whose pursuits (fortunately) are a little less dangerous today than they were a century ago.

By Susan Frith | Photography by Candace diCarlo

By climbing a Tetracentron tree growing on the edge of a cliff … I manage to take some snapshots of the upper part of the Davidia tree in full flower. The wood is brittle, and the knowledge of this does not add to one’s peace of mind when sitting astride a branch … with a sheer drop of a couple hundred feet beneath. However, all went well and we drank in the beauties of the extraordinary tree.—E.H. Wilson, China—Mother of Gardens (1929)

It was the quest for Camellia japonica that stuck Dr. Paul Meyer on a Korean navy boat for five hours with a mind-altering case of seasickness. “I was sure I was going to die,” recalls the F. Otto Haas Director of the Morris Arboretum with a cheerfulness best summoned on dry land two decades later. The hardy, red-flowering shrubs grew on some islands that belonged to South Korea but were located above the 38th parallel, off North Korea’s coast. Due to the military sensitivity of their mission, Meyer, three other American plant explorers, and their interpreter were kept in stuffy quarters below deck as the boat lurched toward its destination.

“I was lying in bed after bouts of vomiting, almost having nightmares, and I’d think, ‘Oh, we’re almost there,’” Meyer recalls. “Then I’d look up and only 10 minutes had passed.”

A lot of trouble, some might say, for a handful of seeds.

Meyer at least was in good company. Ernest H. Wilson survived an avalanche in the 1910s to bring home the regal lily from western China. Frank Meyer (no relation to Paul) fended off a traveling gang of robbers near Feicheng to obtain scions of the succulent pound peach. Civil war, louse-ridden beds, and cholera were but a few of the obstacles that confronted Western plant hunters of an earlier generation.

Today, the Penn-owned Morris Arboretum in Chestnut Hill is home to some 13,000 plants of 2,500 varieties from 29 countries (including healthy specimens of Japanese camellia and a stately Engler beech that Wilson likely collected). It owes its varied inventory to plant exchanges and collecting trips that began in the late 19th century, when the arboretum was a privately owned garden. American nurseries, home gardens, and urban streetscapes benefit from the genetic diversity brought back with these botanic souvenirs. To give a few examples:

- Freeze-trials of dogwoods from Korea, China, and Japan may lead to the introduction of a variety that can survive in areas as far north as Chicago.

- A Korean goldenrain tree that now grows in the arboretum’s parking lot is being studied, along with others, by a Cornell scientist to see how it holds up to multiple urban stresses, including deicing salt, heat, and poor soil.

- The arboretum is working with Penn’s Center for Technology Transfer to patent an Hinoki false cypress collected at a Buddhist temple in Korea. Actually native to Japan, the species may represent an alternative to our native Canada hemlock, which has been devastated by insects.

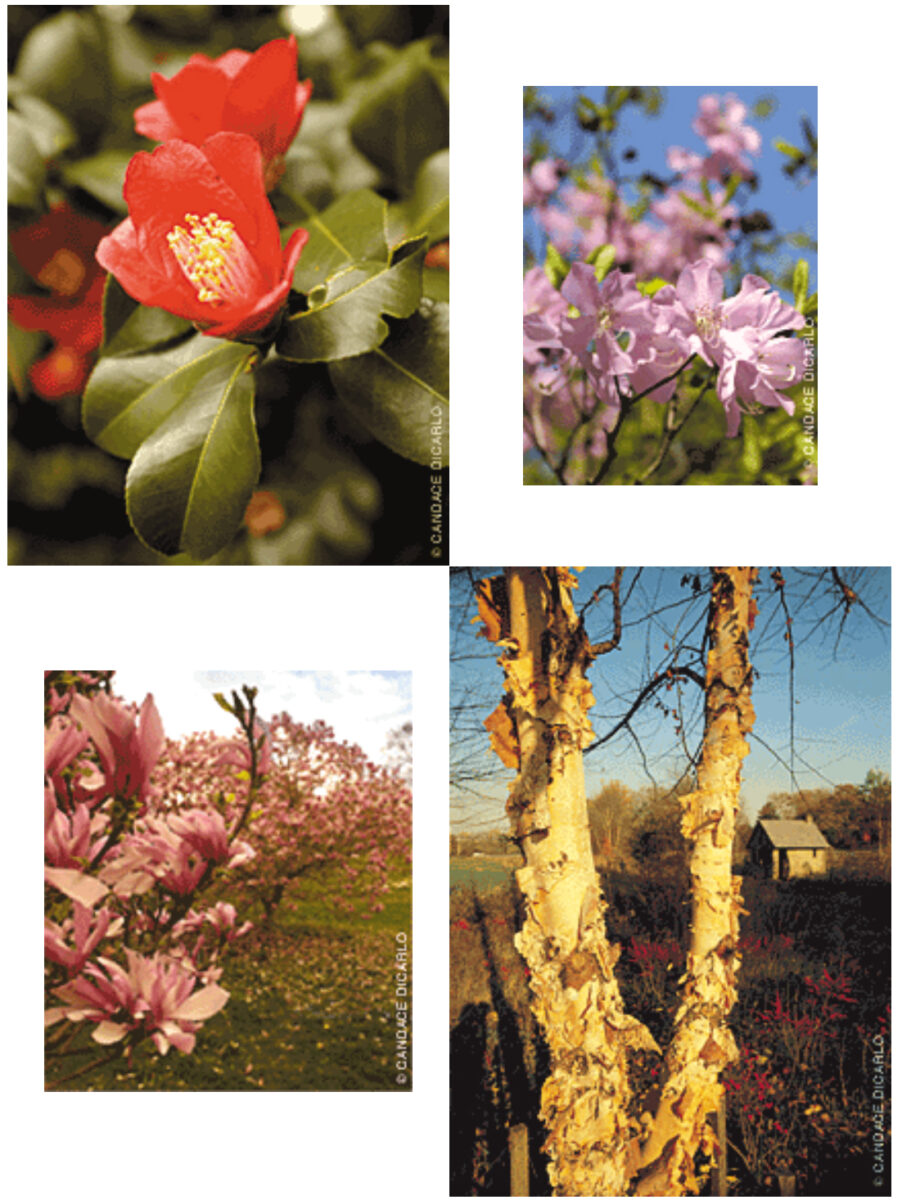

The blue-helmeted grape hyacinths stand at attention as Paul Meyer rides by in the arboretum’s golf cart, his pollen-hued tie flapping behind him in the breeze. It is one of those rare spring days in Philadelphia—a mild respite between a winter that overstayed its welcome and the muggy summer ahead. As we putter along the grounds, the saucer magnolias drop pastel confetti. A mother photographs her son by the weeping Higan cherry. Even the lesser celandines, wildflowers that, in Meyer’s words, are “taking over the world,” are putting on a golden show. But we are not here just to gape at the blossoms.

Meyer pulls up to a paperbark maple, and we get out to take a closer look at the tree, known for its coppery, peeling layers. “It lacks vigor,” he says. “See how short the growth increments are? I believe we’re seeing evidence here of inbreeding depression.” This planting preceded Penn’s ownership of the arboretum and shows the importance of intra-species diversity. Until recently, all the paperbark maples in this country were descended from a few collected by the famous British plant explorer E.H. Wilson; the arboretum collected more on a trip to China in 1994, broadening the genetic stock.

Plant hunting in previous centuries focused on the discovery and collection of plants unknown to Western science. Soybeans, for example, were virtually unknown in the United States until Frank Meyer introduced them from China while working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Though today’s plant explorers may occasionally find a species new to Western cultivation, they focus on recollecting new genetic forms of known plants. “Much of what we grow in this country comes from very limited genetic source material. By recollecting, we’re broadening that material,” Paul Meyer says. Variety within and across species can yield multiple benefits, from an increased ability to tolerate extreme temperatures to a stronger resistance to disease and insects.

“There is safety in diversity; there are dangers in monoculture,” Meyer says, giving the example of Dutch elm disease, which all but wiped out what had been the most popular street tree in America. “The more we tend to plant the same old things over and over again, the more fragile our urban forests become. You could make the same argument for a suburban planting or an agricultural planting.”

There’s no danger of monoculture at the arboretum. Most of its plants come from China, the United States, Korea, Japan, and Armenia, but there are also specimens from Bhutan, Iran, Mexico, Finland, Morocco, and Afghanistan, among other places.

Before Penn took them over in 1933, the grounds belonged to the estate of John and Lydia Morris. Unmarried siblings whose father had owned what was later named the Port Richmond Iron Works, the Morrises were true Victorian collectors. They collected Chinese pottery, Roman glass, Mediterranean coins, garden styles, and many plants. “They were really interested in the world around them,” says Meyer, “and one way they expressed this interest was through these collections.” (They also had the vision that their plant collections would be used as an educational tool for others one day.)

According to Robert Gutowski, the arboretum’s director of public programs, the Morrises acquired some plants on their own travels to Europe and Asia, including cherries John Morris gathered himself in the mountains of Japan. They also bought and sent home ferns from India, bonsais from Japan, and Michaelmas daisies from England. “Matters of homeland security didn’t apply in those days,” Gutowski notes.

The siblings were not exactly rough-and-tumble adventurers—Lydia traveled with her tea set, and they stayed with rajas and other royalty when possible. But “relative to their life here in the United States, they were roughing it,” given the state of travel lodgings at the time, Gutowski says. They also exchanged specimens with Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum and Wilson (who later joined that institution from England’s Veitch Nursery), among others.

Penn’s botany department ran the Morris Arboretum from 1933 until 1975, at which point it became a multidisciplinary research center of the University. After decades of almost no plant exploration, the arboretum sent Paul Meyer (then curator) to Korea in 1979. Since then, the arboretum staff has taken more than a dozen collecting trips—all in collaboration with other institutions. In 2002, for example, Meyer traveled to Armenia with USDA scientists helping that country develop agricultural products for the world market while collecting varieties of pear and other plants. A number of expeditions have been arranged through the North American-China Plant Exploration Consortium, which includes the Morris Arboretum as well as several botanical institutions in the United States and China.

Under most circumstances Paul Meyer is glad to get close to a tree, but the huge log of Tilia mandshurica hurtling toward his minivan was not a welcome sight. During a 1997 trip to China, Meyer and his plant-hunting companions had a harrowing encounter with a logging truck on a bumpy dirt road on the way to Changbai Shan. After the accident, they got out to assess the damage. “To our absolute amazement, the driver side front door had been cleanly ripped off, miraculously leaving the windshield, as well as the rest of the car, intact,” he wrote in his journal. “Had the log hit the van a few inches to the right, it would have caught the frame and … most likely killed the driver, and/or [passengers] sitting directly behind the driver.”

Traffic perils aside, plant hunting today is a considerably less dangerous occupation than it was at the turn of the last century. That doesn’t mean that it is always predictable, however. Some finds have fallen into their laps. Meyer was suited up to give a lecture at Seoul University when he came across a lovely Korean lilac cultivated on its campus. Other plant quests have involved climbing remote mountaintops.

“Hunting plants presents difficulties over and above those connected with hunting big game,” Wilson observed in his 1927 book, Plant Hunting. “The game hunter after finding, stalking and shooting his quarry has but to remove the pelt, dress it and the trophy is won.” The plant hunter, in contrast, “must abide the proper season for securing ripe seeds, roots or small plants … and often several fickle seasons pass before success is attained.” After plants reach their destination, “Then comes the test. Will the new arrivals adapt themselves to alien climates and novel conditions of life? … There are many ‘ifs’ and often months and years of anxious moments pass before the truth is known.”

At the Morris Arboretum, the waiting takes place in several greenhouses not typically seen by the visiting public. Inside the Medicinal House—named for a medicinal-herb garden once planted nearby—the temperature is kept around 35 degrees Fahrenheit to prevent the most vulnerable plants from freezing in the winter.

It requires a little imagination to square these puny contenders with some of the towering adults in the public gardens. Anthony Aiello, the arboretum’s curator and director of horticulture, shows nine seedlings of Meyer spruce that look like dollhouse-sized Christmas trees. Named after Frank Meyer, they are growing from seeds sown in the fall of 2002, after the arboretum’s last trip to China.

“You can see that these little guys have put on new growth,” he says, pointing to sections of light green on the needles. “And this one doesn’t look like it made it.

“We really have to be patient,” Aiello adds. “You can’t rush the plants—they are really on their own time frame.”

Meanwhile, on another workbench, the centuries-old process of grafting goes on with varieties of witch hazel that Aiello collected in England and Belgium in February. Small twigs, called scions, were inserted into grown plants of native witch hazel and held together with rubber bands. They then were placed in the moist environment of a plastic tent for a few weeks. Afterward, they were wrapped with wax tape to keep the graft moist and allow it to knit. As the scion grows, the understock, or host plant, will slowly be cut back. If all goes well, the witch hazel will be ready for the garden in five to nine years, Aiello says.

The process is “a little nervewracking,” he admits. “You go through all this effort—whether it’s a trip like this, or especially if you go all the way to China—and you bring these things back and wait for the seeds to germinate” or the scions to take. “There are a million things that can go wrong. But all we really need is for one of each to take.”

As plants grow, they move from the greenhouses to one of the hoop houses —so named for their rounded frames, which are covered with plastic in the winter and shade cloth in the summer. The hoop houses are semi-crowded way stations for a variety of trees and shrubs, including silverleaf hydrangeas (“a case of a native plant that’s been completely underutilized”) from a collecting trip Aiello took to southern Appalachia and a Yulan magnolia he chanced upon in a villager’s backyard in China’s Shanxi province. A group of manchu striped maples touch the ceiling, pushing for space.

Aiello regards them as a protective parent would a gangly teenager, acknowledging that “at some point these plants need to be put out into the cold, hard world.” Shelley Dillard, the arboretum’s propagator, pushes him along. “She always wants things to move out into the garden and create space,” he says. “She really gives me a hard time if anything has been down here for more than 10 years.”

Before seeds and seedlings even arrive in the greenhouses, they are documented in the plant recorder’s office. Each specimen at the arboretum gets an accession number as if it were a painting in a museum. Field notebooks kept in that office note exactly where each plant was found, what it was growing with, and occasionally such details as luster, hairs, flavor, and odor.

Often, these accessions are seeds, which are picked out of collected fruit and allowed to rot in plastic bags during collecting trips. “You walk into our hotel room and it smells like a winery,” Meyer jokes. Those seeds are cleaned and then shipped with other kinds of samples to U.S. authorities for inspection.

The arboretum’s herbarium contains another record—dried leaves, fruits, and flowers arranged on acid-free paper like works of art. “Herbarium samples can last for hundreds of years and become permanent non-living records of what the plants looked like,” Aiello explains. They also preserve DNA, which can be reconstituted for research.

The best plant-collecting trips yield stories as well as specimens. “What’s a tremendous privilege is to enjoy the culture,” Meyer says. That has, on occasion, meant feasting on sea slugs and bull-penis soup, and drinking toasts spiked with snake urine. “For whatever reason—I’m not quite sure why, because I grew up in the Midwest eating roast beef and mashed potatoes—but I’m just very open to trying new things.”

At 6 feet 4 inches Meyer has sometimes found that he is the specimen under observation. “On our first trip to western China in 1981, in some of the villages we were like creatures from another planet,” he recalls. “My hair was longer then, and blonder—not as grey. As [a colleague and I] walked down the streets of this town, people started following us. Soon we were literally being followed by hundreds of people.” The crowd followed them into a bookshop to watch them look for a book on local flora. Meyer has even had children run up to pet his hairy arms. “I took it all in good humor,” he says.

The karaoke singalongs and special birthday dinners he describes in his expedition reports contrast dramatically with the months of isolating travel logged by earlier explorers.

In the case of Frank Meyer, whose contributions to the Morris Arboretum likely include a Tatar wingceltis, loneliness burdened him even more than danger, wrote Isabel Shipley Cunningham in Frank Meyer: Plant Hunter in Asia. (This, despite the fact that danger came in droves: threatened execution by Chinese soldiers who mistook his group for opium smugglers, attempted roadside robberies, reports of Westerners murdered or held for ransom, and, eventually, civil war.) Meyer himself observed that: “Loneliness always hangs around the man who leaves his own race and moves among an alien population.”

Only the conviction that he was doing important work made it worthwhile. “I never get through with my work here,” he once wrote.

In May 1918 he disappeared on a riverboat going down the Yangtze. Though Meyer’s body was later recovered from the river, the circumstances of his death remain a mystery.

E.H. Wilson predicted that after a “golden age” of plant exploration in the 19th century—when the world’s “most secret corners had been penetrated and their riches exposed”—followed by a revival of interest in Asia in the early 20th century, the era of the professional plant explorer would come to a close. That hasn’t proved to be the case.

“Certainly there is so much to be learned in the tropical world,” the arboretum’s Paul Meyer says. “There is also a lot to be learned in the temperate world,” though plant exploration will likely continue to focus on new populations of known plants and a careful effort, he hopes, to prevent the propagation of invasive varieties. No one wants another kudzu. “I find myself pulling back the reins of my commercial colleagues who want to introduce a plant too quickly, before it’s been fully tested. We grow plants at the arboretum for many years and evaluate their potential for invasiveness.” Fortunately, he says, “There are lots of plants that are perfectly well behaved and are not a problem.”

This fall, Meyer will travel to the former Soviet republic of Georgia with a colleague from the USDA to collect apples, pears, an oriental spruce, and a heat-tolerant nordman fir.

“I think the only thing that’s going to limit us [in plant collecting] is the disappearance of so many natural areas around the world,” he says. The camellias Meyer and his companions found on the South Korean islands two decades ago were actually growing on pastures grazed by goats; their habitat was destroyed. “Because the Korean villagers loved and respected camellias, they saved them, but the goats were eating everything around them,” Meyer recalls. “When the camellias die there, I’m afraid there’s not a younger generation that’s going to take their place. Losing that particular population is a real genetic loss.”

At least their legacy continues in the United States. A California nursery is introducing a cold-hardy camellia, “Korean Fire,” derived from seeds collected by a colleague of Meyer’s on the 1984 trip.

Meanwhile, Meyer watches the arboretum’s own camellia plantings year after year with Darwinian interest to see which ones will hold up best to a harsh winter. Most greet the spring with glossy green leaves and a profusion of red-cupped blossoms. “It’s absolutely remarkable how well these are doing,” he says.

Not a bad payoff for a handful of seeds.