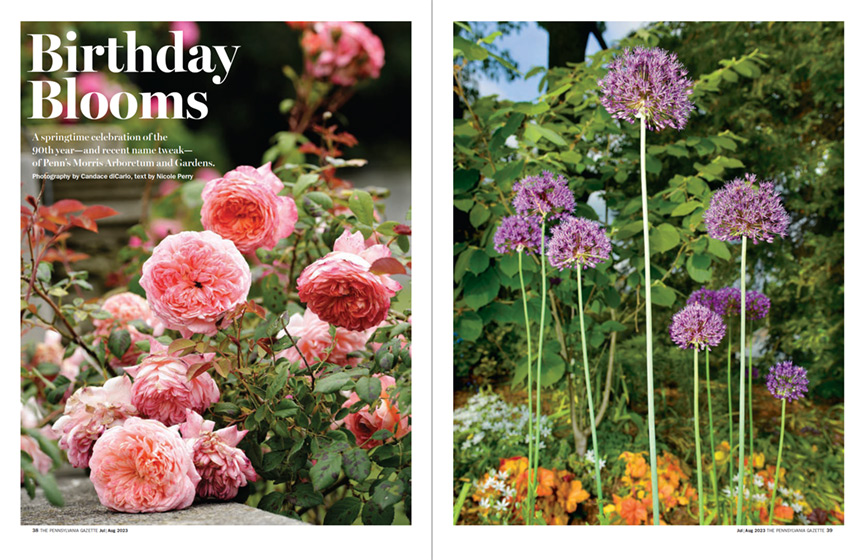

A springtime celebration of the 90th year—and recent name tweak—of Penn’s Morris Arboretum and Gardens.

Photography by Candace diCarlo, text by Nicole Perry

Plus | Slideshow

On June 4, 1933, after functioning as a private estate for siblings John and Lydia Morris, the great iron gates of Morris Arboretum opened to the public. As they swing open 90 years later, the institution unveils a more descriptive name, new features, and additional events and programs.

The name change—now it’s Morris Arboretum and Gardens—harkens back to the Morrises’ shared vision of a public garden where conifers, hollies, magnolias, and other trees live in harmony with an artist’s palette of colorful flower gardens, according to Bill Cullina, F. Otto Haas Executive Director.

“The new name is really a reflection of what was already here—we have always been more than just an arboretum,” Cullina said in an email provided from the arboretum. “When John and Lydia Morris first created this place, they crafted beautiful gardens, like the Rose Garden and Flower Walk, to add color, beauty, and interest in addition to building a diverse collection of trees.”

The pair was also keen on transforming their estate, which they called Compton, into an institution for horticultural research. After Lydia’s death in 1932 (John had died 17 years earlier), the land was bequeathed to the University, which would serve as a steward for the siblings’ shared dream [see “Old Penn,” this issue, for more on Morris’s history].

Arboretum officials point to an increased focus on molecular science, an emphasis on color and beauty, more accessible pathways, and a celebration of pure joy as fresh features of the newly rebranded Morris Arboretum and Gardens.

The Garden Railway, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, is one example of the institution’s commitment to delighting visitors. It received a new, 300-foot track extension, making it one of the largest garden railways in the country, at one-third of a mile. This is the largest one-time expansion since the railway’s installation in 1998.

The exhibit’s theme this year is “Public Gardens” and features miniature models of real-life structures and elements from gardens across America, like a cactus gallery from the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix and Queen Anne’s Cottage from the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden. Through loops, tunnels, and bridges, the train also passes scaled-down versions of local landmarks, like Philadelphia’s city hall and art museum. Created by Kentucky-based botanical artists Applied Imagination, the replicas are constructed with natural materials like bark, moss, flowers, and shells. Independence Hall, for example, is crafted with pinecone seeds for shingles and twigs as downspouts.

The enhanced Garden Railway is open through October 10, at which point it will close to prepare for the popular Holiday Garden Railway exhibit, opening November 24.

A brand-new exhibition, Exuberant Blooms: A Pop-Up Garden, is open through October 1. Paying homage to the grandeur of the Victorian floral carpet, it’s a vibrant display of more than 10,000 plants of varying color, form, height, and shape. Plants range from as small as eight inches to as tall as eight feet.

Seven large paisley-shaped “plant islands” are spread over more than a quarter acre. Each bed contains a wide variety of annual and tropical plants known for their bold, saturated colors and their appeal to pollinators, such as bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. Plants like dahlias, cannas, zinnias, euphorbia, salvia, and colocasia impress with deep purples, bright pinks, and cool blues. Arboretum officials share that some specific varieties include Calibrachoa Cabaret ‘Midnight Kiss,’ Angelonia Alonia ‘Pink Flirt,’ Canna ‘White Tiger,’ Colocasia ‘Black Magic,’ and Cleome Senorita ‘Rosalita.’

The Rose Garden has also received a facelift and become more accessible for people with mobility issues, Cullina said. Bluestone pavers have been installed on the two central axis walkways, making it easier for visitors of all ages and abilities to get close enough to experience the flowers.

One of the oldest features of the Morris estate, the Rose Garden dates back to 1888 when it was originally comprised of just a few roses mixed in with fruits, vegetables, flowers, and a specimen chestnut tree, according to archival history on the Morris’s website. Lydia Morris transformed it into a monoculture rose garden in 1924. Today, it blooms with perennials, annuals, and woody plants, along with roses and ornamental elements that harken back to the Victorian era.

Another new project that Cullina is excited about includes progress on a molecular lab that he says will be transformational for the research staff. The research center currently studies the evolution, phylogenetics, systematics/taxonomy, anatomy, and morphology of plants. Floristics, or the study of what plants grow in a certain place in a particular timeframe, is also a major focus, especially the flora of Pennsylvania. According to its website, the Morris is fundraising for a suite of molecular biology and anatomy/histology tools and equipment that will allow the staff to grow the research program even further.

“Lydia gifted the Morris to the University of Pennsylvania so it could become a place for botanical research, horticultural education, and public engagement,” Cullina said. “With the expansion of our research program, educational opportunities for children, students and adults, and a focus on responsive and engaging visitor experience, I believe we are celebrating Lydia’s gift in all we do.”

The Morris also plays an important ecological role in the sustainability of our planet, Cullina said.

“We speak for the trees, and our trees are in trouble: climate change, introduced insects and diseases, invasive species are destroying our forests,” he said. “We are focusing on the taxonomy and conservation of rare species and restoration of imperiled trees such as American ash, Canada hemlock, and American beech.”

Another important ecological endeavor is the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project, which is seeking to understand “what thrives, survives, or perishes in cities, now and in the past,” according to Morris’s website. The Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis, stretching from New York to DC, is the oldest urban corridor on the continent and presents a unique opportunity for studying the urbanization of flora. Researchers at Morris and its partner organizations are digitizing roughly 700,000 herbarium specimens from 11 institutions in this urban corridor.

“As we stand on the cusp of our second century, I am aware that our role as a research institution and a place for joy and healing has never been more critical,” Cullina said. “I believe that regular contact with the natural world is an essential part of our humanity. These 165 acres of meadows, trees and gardens in such a heavily urbanized region are a true gift of health, peace, and well-being to our community.”

Slideshow

Photography by Candace diCarlo