William Curtis Farabee conducted pioneering studies of the Amazon for the Penn Museum in the early part of the 20th century. His journals and notebooks offer extraordinary glimpses of the area’s indigenous peoples, and the artifacts he brought back offer an unmatched—and still largely unexamined—treasure-trove of cultural materials.

By Beebe Bahrami | Photos courtesy of the Penn Museum

Sidebar | A Pioneer’s Notes

In late April of 1914, six men walked out of the bush and into the streets of Georgetown, British Guiana, gaunt, fever-ridden, clothes in tatters, four not wearing much clothing at all. The four were natives of South America—two members of the Wapisiana tribe (also called Wapishana), one Taruma, and one Ataroi (also called Atorad). The other two were a Scotsman named John Ogilvie, who had settled in the region a decade-and-a-half earlier, and an American, William Curtis Farabee, a Harvard-trained anthropologist working for the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, who had been dispatched the year before to head an ethnographic and archaeological expedition to the continent. “We were declared the toughest looking men who had ever entered the city,” Farabee wrote in A Pioneer in Amazonia, his 1917 account of the expedition.

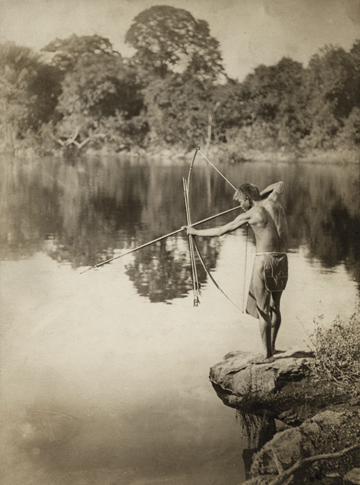

Though not much remembered today, Farabee was indeed a pioneer in studying the indigenous peoples and cultures of the Amazon. He wrote about several Amazonian peoples, offering moment-in-time glimpses of their world prior to greater contact with the Western, industrial world. He also carried out archaeological excavations, such as at Marajo Island at the mouth of the Amazon and on Nazca sites in southwestern Peru. Among the indigenous groups he met were the Wapisiana, the Macusi, the Waiwai, the Taruma, the Atarois, the Parikutu, and the Diau (all his spellings). He organized his work by linguistic families, the Arawak and the Carib language groups, publishing The Central Arawaks in 1918 and The Central Caribs in 1924. He also stopped along the way during his Amazon expedition to sketch and map petroglyphs on rocks and caves to document the past of groups that may have already perished or that offered some insight into the ancestries of contemporary groups.

Even though Claude Levi-Strauss’s book Triste Tropique, published in 1955, “is the most celebrated” study of indigenous Amazonian societies, Farabee’s work “is a major contribution; it lay the groundwork for what came after it,” says Greg Urban, the Arthur Hobson Quinn Professor of Anthropology and a consulting curator in the museum’s American Section.

Farabee had reached South America in late July 1913, arriving in Manaus, Brazil, after several mishaps with transport—a leaky ship, a resigning captain, and a drunken first-mate—and with customs officials. Traveling with Farabee from Philadelphia was a Dr. Franklin H. Church, who was interested in studying tropical diseases. Between September and November, along with a young Brazilian named Joaquim Albuquerque hired after their arrival, Farabee and Church explored Boa Vista in northern Brazil and the Rio Branco, a branch of the Amazon. From there, they pushed on into largely unexplored parts of British Guiana and northern Brazil. They headed toward Dadanawa, a settlement along the Rupununi River in south-central Guyana, then a part of British Guiana—and toward one of the great adventures of Farabee’s life.

“The explorer sets out to make a definite journey,” Farabee wrote in A Pioneer, “and bends all his energies to that one definite task. The ethnologist on the contrary only sets out, the journey develops and its direction is determined by the presence or absence of friendly or unfriendly tribes.” So it happened when he and Church arrived northeast of Boa Vista, in Dadanawa (which Farabee writes as Dada Nawa).

“When we went to Guiana,” Farabee continued, “we had no idea of making a long trip into the forest country, but at Dada Nawa, the home of Mr. H.P.C. Melville, magistrate and protector of Indians, we met Mr. John Ogilvie, a native of Scotland, who had spent several years prospecting for gold and rubber and was well acquainted with the whole region. From him we learned of tribes in the forests who had never seen white men. He himself has been the first to visit some of their villages. We persuaded him to take some of his Wapisiana Indians, whose language he spoke perfectly, and to go with us to see some of the interior tribes. Mr. Melville took a great interest also in our expedition and gave us every assistance possible.”

Ogilvie was fluent in Wapisiana, as was Melville, and deeply knowledgeable about both Arawak-speaking and Carib-speaking peoples in British Guiana and Brazil. He had been in British Guiana for 14 years at the time Farabee met him. Melville, also a Scotsman, had arrived 25 years earlier, bought a herd of cattle from a Dutchman, settled at Dadanawa, and married a local Atorois chief’s two daughters.

(I’m indebted to environmental anthropologist Thomas B. Henfry’s 2002 dissertation “Ethnoecology, Resource Use, Conservation, and Development in a Wapishana Community in the South Rupununi, Guyana,” for details on Farabee, Melville, and Ogilvie, and especially on Melville’s history. This exceedingly easy-to-read and well-written work—available at http://lucy.kent.ac.uk/csacpub/Henfrey_thesis/—offers a current picture of the same people and the same part of the world that Farabee explored between 1913 and 1916.)

Farabee asked Ogilvie to select four indigenous men to act as local guides. These men were considered the most skilled in many areas—hunting, social customs, and languages of the area’s tribes, as well as being generally uplifting people to be around. This latter point was especially comforting when it was raining, no game was around, the fruit- and nut-bearing trees were elsewhere, and one or all of them was running a fever. Or when the thin-skinned bark canoes they traveled in started to leak—which was often—and they had to build new ones.

On November 19, 1913, the core group of seven men—Farabee, Ogilvie, Church, two Wapisiana, one Ataroi, and one Taruma (whose names go unrecorded in Farabee’s accounts)—departed in an expedition party 62 people strong. The additional 55 people included more than a dozen native men contracted to carry packs, supplies, and trunks on the first leg of the journey, along with their wives, children, dogs, and chickens. Everyone carried something, except “[o]ne great-grand-father, too feeble to carry a pack, [who] added a little dignity to the lively party,” Farabee wrote.

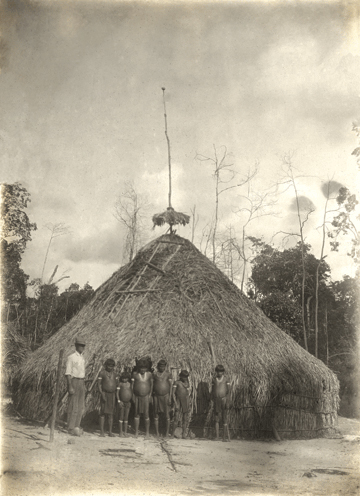

Farabee soon learned that the world around him was alive with history and meaning, as when he records how the group stopped to offer grass at a natural shrine or uttered a prayer in passing a fallen tree. They were passing through the Wapisiana’s sacred landscapes, considered their traditional home, and onward into territories covered with ancient petroglyphs, tributaries, savannahs, mountains, and forest. They entered and were invited to stay in villages occupied by Wapisiana, Taruma, Waiwai, Parikutu, Chikena, and Diau. They followed old indigenous trails to villages as well as rivers and tributaries, mapping them as they went. When necessary, they made new trails.

The group shrank and expanded as the commissioned carriers reached designated locales, or as river waters rose and fell, making water transport easy or difficult. It was a constant adjustment, and Farabee was not traveling light—part of his mission was to build one of the biggest South American collections in North America for the Penn Museum, ultimately amounting to more than 4,000 pieces of archaeology and ethnology shipped back to Philadelphia.

(For a variety of reasons, including Farabee’s failing health in the 1920s, ultimately leading to his premature death in 1925, as well as the sheer size and variety of what he sent back, large parts of the collection remain unexamined today, some 90 years later, according to William Wierzbowski, assistant keeper of the Penn Museum’s American Section.)

Shortly after Christmas 1913, the party, of necessity, became very small. Farabee wanted to travel eastward to even more remote tribes, but no trails or canoes existed between these places and the party would have to rely entirely on what they could gather, hunt, or fish. It was down to the six who would four months later wander into Georgetown.

Church turned back toward Dadanawa with the larger party and with Farabee’s filled journals, collection crates, and photographs. Until then, everyone had remained healthy. After this point, though, fevers set in, both for Church’s group and for Farabee’s.

Farabee and his companions had to make their own trails, anticipate treacherous waterfalls by discerning the ominous sounds of rushing water, tend to a poisonous snake bite and perennial high fevers, and pull through days without food. (They also had to deal with the aftereffects when food was finally found: Ogilvie shot an alligator and everyone ate so fast and so much that they could not, as Farabee joked, “keep their alligator down.”) But this was also a time when they met with some of the most enchanting peoples in their travels. For instance, of a Parikutu village along the Apiniwau waterway, Farabee writes, in A Pioneer, “[We] spent two weeks with them so pleasantly that when we were ready to go, Ogilvie said, ‘what a pity we must leave such splendid people’.”

They headed on, north along the Honawau River where they sought out a Diau village and then continued toward the border with British Guiana and Brazil and the Corentyne River, where they hoped to make their way out of the jungle. Conditions grew even harder. Food was scarce, quinine was running low, on any given day someone had a fever, and navigation was tough. To add to their troubles, they had left the area where the trees from which they harvested bark for their bark-canoes grew, so that when the canoes grew thin and brittle, they could not make new ones.

“For twenty-six days we worked our way down this difficult and dangerous river without seeing a single human being on the way,” Farabee wrote in A Pioneer. At one point even the upbeat, indefatigable Ogilvie lost spirit: “[I]t was at night after a hard day working over the rocks with a raging fever and without food. My first time had come a few days earlier under similar circumstances. But in both cases the depression disappeared along with the fever and daylight found us looking for a passage and grub—or grubs.”

When they finally made it out of the bush, they then had to deal with civilization’s jungle—taken into police custody while they awaited permission to cross into British Guiana. “Apparently we had no satisfactory explanation for being in the country,” wrote Farabee, who at that point was suffering from fever. “The discussion continued until every prominent man in the city had been sent for and had had his say about the matter and until every one of the collected mob had had his look. One is not likely to enjoy such attentions with a body temperature of 104°.”

After three hours, the judge, impressed by the “amount of our letter of credit” allowed the party to cross to the British side of the river. Once in Georgetown, the six men wasted little time in purchasing new clothes and getting cleaned up. Ogilvie and Farabee also introduced their four native guides to the city and its oddities, such as suits, trains, cars, and motor boats—about which Farabee remarks admiringly on their self-possession: “Through it all they showed no sign of fear, surprise nor delight, neither did they seem awkward in their first suits. This does not mean that they were stupid, unimpressed and uninterested. It is only an example of their complete self-control … They observed everything but without demonstration.”

Ogilvie, the two Wapisiana, the Taruma, and the Ataroi soon returned into the hinterland to go back to their homes, via a more navigable route. Reflecting on their experiences, Farabee wrote that Ogilvie, “with his fourteen years’ experience in river and forest exploration, was of inestimable value to the expedition. He is the best man I ever saw for such work.” And while he didn’t see fit to include their names in his narrative, Farabee clearly had great respect for the guides as well. “Every one of the Indians we selected proved himself worthy of the confidence we placed in him,” he wrote. “I was constantly surprised at the number and variety of things they knew.”

Farabee himself went on to Barbados via Trinidad, where he stayed for 28 days recovering from fever and malnutrition. (He had lost 48 of his maybe 180 pounds while in the jungle.) In Barbados he met Theodore Roosevelt, who was recuperating from much the same sort of experiences as Farabee. Since leaving office in 1909, the former president had embarked on a series of expedition-like explorations. In 1913, the same time as Farabee, Roosevelt explored the Brazilian Amazon, resulting in his book Through the Brazilian Wilderness (1914), where he mentioned Farabee. The Penn Museum received a letter from Roosevelt, dated October 30, 1915, that spoke of his great admiration for Farabee’s work.

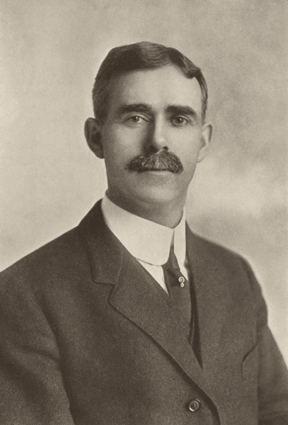

Photos of Farabee show a stoic fellow with a magnificently thick and well-trimmed mustache, his face something of a cross between Kevin Kline and Clint Eastwood—perfect casting as a romantic explorer-scholar, going into the unknown with courage and stamina. He was already 48 years old when he took up the lead of the South American Expedition. He had been to the continent a few years earlier as part of an expedition sponsored by Harvard University, where he received his doctorate in 1903 and taught until joining the Penn Museum as head of its South American Expedition and a curator in the American Section.

Farabee’s proposed salary was $3,000 a year, to be increased to $3,500 when he returned from South America. He accepted, less for the money, one suspects, than out of a sense of moral duty—to document indigenous peoples before their cultures were more heavily altered by Western contact—and the chance for adventure.

This was an era is which museums around the country were racing to build the biggest and best ethnological, archaeological, and naturalist collections. Scholars like Franz Boas, known popularly as the “Father of American Anthropology,” George Byron Gordon, then the director of the Penn Museum, and Farabee were also greatly concerned about the vulnerable state of indigenous cultures. The Amazon had recently made its way into the international media with a scandal revolving around the atrocities of Peruvian rubber baron Julio César Arana, who was alleged to “have killed some 30,000 out of the 50,000 inhabitants of the Putumayo area,” a tributary in the Amazon, says Eleanor M. King Gr’00, an assistant professor at Howard University’s sociology and anthropology department and an archaeologist with a special focus on the history of anthropology, rainforest environments and ecology, and the Americas. “The scandal began in 1909 when a British newspaper began publishing the facts,” she explains. “A special investigation by the British was published in the summer of 1912 and in the spring of 1913 Arana was questioned [before Parliament]. By 1911, the scandal had already been rocking the international community.”

Starting in the 1850s, the Amazon was the stage of a lucrative multinational rubber boom. Its decline by the 1920s came about quickly, especially after the first successful attempt at cultivating rubber trees outside of the wild Amazon basin took hold in Southeast Asia, a market shift stimulated by the greedy maneuvers of rubber barons in Manaus, Brazil, who were pushing up prices. “There was a spectacular crash of the Manaus market in 1913 that left it a ghost town, where before it had been this extravagant, bustling, world-class city. Southeast Asian production kicked in right after the peak of Amazon rubber production in 1911,” says King.

“Back at the museum, you get Boas writing to Gordon in 1911 urging salvage ethnography of the Amazon area,” she adds. “My guess is that the need became urgent as news began leaking about what was going on down there. It was then that the Museum began planning an expedition.” Gordon recruited Farabee, whom he had known when he too was at Harvard, and by 1913, Farabee was on his way. For this three-year expedition it appears he left his wife, Sylvia, behind, though she accompanied him when he returned to South America in the 1920s.

In 1917, one year after Farabee’s return from the Amazon, he served in the U.S. Army’s Intelligence Corps. When World War I ended in 1918, “he was put in charge by Woodrow Wilson to draw up cultural maps of the world,” notes the Museum’s senior archivist, Alessandro Pezzati. Wilson appointed Farabee the lead ethnographer in the American peace commission toward this purpose. His work was used in an advisory capacity to help the diplomats who created the Treaty of Versailles determine new national boundaries, though Farabee was not a part of this latter endeavor. Pezzati considers this perhaps Farabee’s greatest contribution as an ethnographer.

After the war, Farabee returned to his curatorial post in the museum’s American section. In 1921, President Warren Harding sent him as a special diplomatic envoy to Peru, the land of his first serious South American fieldwork from 1906 to 1909. In 1922 Farabee returned again to South America for ethnological and archaeological fieldwork, this time focusing on Peru and Chile. But that would be, in hindsight, a fatal trip; during it, he contracted such a fierce tropical illness that it would unravel his health and lead to his death in 1925, at the age of 60.

Amazonian studies—and realities—have changed a lot since Farabee’s time. Today there are many more grassroots political movements and organizations and greater self-determination among indigenous groups, political and cultural revival efforts, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) fueling efforts economically, culturally, and environmentally. And we now have native ethnography, in which people are studying and recording their own indigenous culture, adds Penn’s Greg Urban.

A cultural anthropologist specializing in Amazonian languages and cultures, Urban lived for three and a half years among the Laklano and Kaingang peoples of southern Brazil, who speak languages within the Jê language family. Unlike Farabee, he and his wife stayed in one place, learning to live as locals.

Farabee “was at the tail end of the explorer-anthropologist [era],” says Urban. “His books are incredibly invaluable because he may have been the first person to go and describe what he saw, but the depth of any group was missing.”

“I think his [greatest contribution was the] documentation of a number of different tribes on the Amazon and its tributaries at a time when their life ways were rapidly vanishing,” adds Howard University’s King. “His holistic anthropological approach—recording everything from physical anthropological characteristics to language to culture and even archaeology (he dug at Marajó) is illustrative of the early days of professional anthropology in this country.”

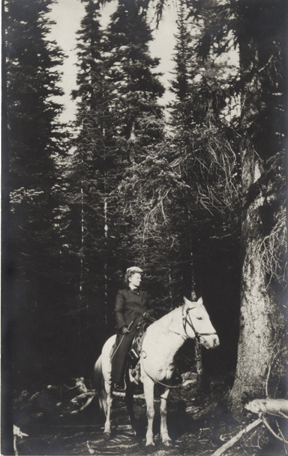

“My dear Dr. Gordon,” wrote Sylvia Farabee from Ica, Peru, on June 8, 1922, “Mr. Farabee is here very ill with inflammatory dysenteria. He took sick in the interior one hundred and fifty four miles away. As there was no physician he had to come here. He rode on horseback fifty-two miles the first day, then went to bed and sent for an automobile which arrived three days later. He has had an awful journey in a Ford car over the trail of the Pampa Huahuari to Ica a distance of one hundred miles where he arrived more dead than alive. Doctor says if he had been two days later he could not have saved his life.”

Farabee had been excavating a Nazca archaeological site in Peru when he fell ill. From Ica he went on to Arequipa and then to Juan Fernandez Island, all in pursuit of suitable places to recover his health. Aware that he was not strong enough to make further expeditions of any great physical challenge, he made one more journey, to collect ethnographic information about the Araucanian natives in central Chile, before boarding a ship to Philadelphia where he arrived in the spring 1923.

Doctors determined he had a “pernicious anemia” that had settled into his body, most likely from his bout with diphtheria. Farabee’s efforts to reclaim his health continued for two years, and included receiving around 35 blood transfusions. Before he fully retired to his home in Washington, Pennsylvania, where he was born and had grown up, he spent some time in West Virginia, living as simply as possible. His obituary in Washington’s newspaper, the Observer, described that as a time “when he roamed through the fields, hunting and fishing, wearing only a breechcloth, such as was worn by the aborigines.” It makes one wonder if Farabee felt betwixt and between after so much time in another part of the world, if he was trying to capture what he had lost. Though he regained some strength from that time, when he returned to the museum his health soon took another turn for the worse. He died on June 24, 1925.

Though Farabee is relatively unknown now except to anthropologists who study South America, he was viewed as a prominent figure in the field at the time of his death. Newspapers across the country, from Philadelphia and New York, to Boston, to Columbia, South Carolina, ran respectful obituaries. Many made the point that he gave his life for his work—and he did.

Beebe Bahrami Gr’95 is currently researching a book, The Spiritual Traveler—Spain: A Guide to Sacred Sites and Pilgrim Routes, due out March 2009 from HiddenSpring Books (Paulist Press).

SIDEBAR

A Pioneer’s Notes

Farabee’s surviving notes and journals from his 1913-16 South American expedition, as well as others he carried out for the Penn Museum through 1922, now reside in the museum’s archives. “We have about 30 notebooks from Farabee,” as well as other records such as correspondence, photographs, glass slides, books, and articles, says Alessandro Pezzati, the museum’s senior archivist. “His handwriting is fantastically bad, and he wrote in pencil on paper that is now brown, so the reading of them may be tedious. But they [are] fun,” Pezzati adds. “I remember one passage where he is taking pictures inside a house in Peru when an earthquake strikes, so he moves his camera under the doorway and keeps taking pictures, completely unfazed. He was a fascinating individual.”

Measuring five by seven inches, with stiff medium-brown covers and very yellow pages, Farabee’s notebooks are a delightful hodgepodge: copious notes of observed everyday life and customs, folklore, myths and legends, native drawing designs, foot and hand tracings of different individuals, physical-measurement charts, linguistic-comparison lists and graphs, notes on local cat’s cradle string-design methods that read like a knitting kit, lists of provisions (matches, 14 coats, 4 trousers, 9 shirts, 5 powder caps, knives, cups, spoons, machetes, photo materials, milk, butter, raisins, sugar, corn biscuits, pickles, jam, sausage, fruit, peas), and trade inventory (cloth, mirrors, combs, thread, buttons) and collections (combs, clubs, trays, fans, sandals, dance rattles, necklaces, whistles, feather crowns, ear ornaments, stools, sieves, graters, mortars, hairtubes, belts, baskets, arm bands, arrow point cases, cassava strainers … ). Indicating some musical training, he also includes musical notations, capturing the notes, key, tempo, and melody of ritual songs he heard sung in several Amerindian villages.

Farabee also kept a more chronological set of loose-leaf notes that help piece together the order of the notebooks. Still, if it were not for his published works, it would be hard to make complete sense of his overall expeditions. He seems to have used the notebooks as shorthand, a memory aid to be expanded on later. His publications reveal details he recalled after the fact, and with greater emotion.

In one dramatic instance, from a time when Farabee was overwhelmed by fever, navigating difficult terrain, and beset with frequent food shortages, on March 15, 1913, he wrote: “Old man said we had traveled too fast—we should wait ’til spirit caught up and [so we] got away at 11:00 [a.m.]” Later, in his published account, A Pioneer in Amazonia, he elaborated on the same event: “When the dance was over or rather when the food was exhausted we started home [back to another Amazonian village where they were briefly staying] with an old trader [possibly of the Diau tribe] who lived twenty-eight days northeast of this village. He and his people had been drinking and dancing until they were so nearly exhausted that they traveled very slowly. We were in the habit of walking fast until we encountered game or until afternoon when we would camp and go hunting. The second evening they got into camp late. In the morning when we were ready to start he refused to move, saying that we had traveled so fast the day before that his soul had not been able to keep pace and that he would have to wait until it caught up. About eleven o’clock it came in and we got away but it was so tired we made a very short journey.”

While Farabee’s published accounts may provide more detail, what is unique about his notebooks are the spontaneous records of immediacy and of being in the thick of things. Moreover, there are wonderful blurts in his notebooks that that have little to do with the context of the writing on the page around which they occur. One reads: “Men and women seem affectionate.” Case open and closed. Another: “Measured Waiwai hair—man 28 inches long.” Don’t you wonder what the Waiwai man was thinking? Or: “They have no flood story,” revealing the comparative mythologist at work, looking for a universal in the stories (or the evidence of Christian missionaries). Or, more personally: “Birthday—2 plantains,” noted on his birthday of February 7, and a stark “Xmas dinner,” noted on December 24. In A Pioneer we get more about the latter occasion: Farabee’s group was actually at a Waiwai village dance: “[it] reminded us of somewhat

similar occurrences which were taking place at home. We celebrated Christmas the next day as best we could with the thermometer at 94 degrees.”

—B.B.