Remembering three atypical educators.

By Carl Hoffman

It’s funny what you remember about a place a long time after you have left it. Your grandmother has been dead for 40 years, and one morning while riding in a Bangkok tuk-tuk you unexpectedly taste her cheesecake. It has been almost half a century since you last saw your childhood neighborhood, but one moment, on a boat at sea, you’re somehow smelling the lilac trees that grew in your backyard. You’ve been out of touch with an ex-girlfriend since Jimmy Carter was president, and last night you unaccountably dreamt of her sister.

I have not been back to Penn since the somber day I departed, once and for all, on August 31, 1984. It’s nothing personal against the University—I’ve scarcely been back to the United States at all from that day to this. These days I find myself remembering my courses less and less, and the mere incidentals of my academic life more and more. And lately I find myself recalling in great detail three extraordinary people I hadn’t thought of since the last time Philadelphia appeared in my taxi’s rearview mirror: three people I knew simply as the Duck Lady, the Professor, and the Vent Man. I remember them with affection and, with an insight that eluded me in my youth, the respect one accords to great teachers.

I came to Penn as a graduate student after living in the Satyricon that was New York in the 1970s, where I had schmoozed with people who thought they were Jesus, met guys dressed in gorilla suits, and encountered one old man who swore that pterodactyls swooped down on the city from the New Jersey Palisades at certain nights of the year, carrying human babies in their talons to feed to their young. Compared to this, my friends sagely predicted, life in Philadelphia would be one long bland bore. But after stepping off the train at 30th Street Station and wandering onto Penn’s leafy campus, the first person I encountered was the Duck Lady.

I heard her before I saw her. Blasting away from somewhere to my left was a low, raspy, almost cartoonish voice yelling what sounded like, “Pah! Pah! Pah!” I looked around. The noises were coming from a disheveled old woman sitting on a bench, wearing a filthy dress, trying to drink whatever was left from a small discarded milk carton as she convulsed to the rhythm of her percussive outbursts. In hindsight, I suppose that she suffered from Tourette’s Syndrome or some other neurological disorder. At the moment I first saw her, however, she was quite simply weird—wonderfully, fascinatingly weird.

I soon learned that the uncharitably named Duck Lady was both a fixture on campus and a celebrity throughout West Philadelphia. You saw her literally everywhere, and you could often hear her in the vicinity without actually seeing her, as she trod a nearby street yelling, “Pah, pah, pah.” Usually an object of ridicule, she was sometimes treated with indulgence. I once saw her “buy” a cup of hot chocolate at Roy Rogers from a young black woman at the counter who let her “pay” with five pieces of Styrofoam, torn from a discarded cup.

The last time our paths crossed, she was as bedraggled as always, but lucid—perfectly, totally lucid. Sitting in a charity-run thrift store amidst piles of used clothes, dingy old housewares, and broken-down kitchen appliances, she was telling the store clerk about her former life. There had been—at one time—a home, a husband, children, and an identity that no one would have thought to demean with a name like Duck Lady. She sat quietly for a moment and said, “Those were good times. Everything was very nice.”

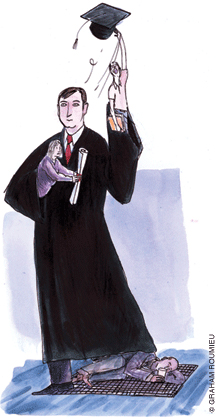

The Professor was somewhere in his 50s when I was at Penn, slim and narrow shouldered, around five-foot-seven and no more than 100 pounds when soaking wet. He was often, in fact, soaking wet—or sunburnt, sweaty, and windblown from a life spent almost totally outside. A fixture on campus during the balmy months of spring, summer, and fall, he would walk briskly around the Quad—clad in worn-out pants, short-sleeve jerseys, and loafers—glance occasionally at a non-existent watch, and mumble to himself irritably about being “late for class.” His overall look, augmented by unkempt long hair and a goatee that was always getting lost in the stubble that surrounded it, was that of a deep-thinking intellectual, an iconoclastic genius too preoccupied with cutting-edge ideas to care about clothes or grooming. But the lecture halls where students eagerly awaited his arrival existed only in his mind. Stated simply, the Professor was insane.

Some people said that he had actually been a Penn professor who had tragically lost his mind and ended up out of work and homeless. Others disagreed, citing actual, functioning, well-respected Penn professors they had studied with who were, if anything, crazier. Most observers, however, were convinced that the man had never had much contact with higher education, and that he had developed his mannerisms from watching too many movies and TV shows lampooning lovably befuddled “eggheads” and “crackpot” geniuses—Hollywood’s usual depiction of the learned professions.

However he may have come by his character, he played it rather well. First, there were his notebooks. I never saw the Professor without an armful of spiral notebooks, which he carried around as he rushed from his imaginary undergraduate lecture to his make-believe graduate seminar. Tattered and covered with a dark patina of age, these notebooks were likely discarded by some long-gone student before becoming emblems of the Professor’s persona. I never knew what, if anything, they contained, but I did manage to notice that the writing samples on the covers consisted of scratches and scribbles.

Then there were his impromptu discussions with students lucky enough to catch him on his way to a fanciful meeting with the Dean, or off to advise one of his numerous imaginary doctoral degree candidates. Needless to say, these inconvenient but necessary curbside conferences occurred often, as there was never a shortage of students eager to jolly the Professor along and have a good laugh. I recall wandering by one of these sidewalk symposia as the Professor, speaking animatedly with liberal use of hand gestures, was saying, “Now, I’m not talking about mere cosmic happenstance. I’m talking about the spheres!”

On occasion, he made sense. I remember a warm spring day, perhaps the first really warm day of the season. Flowers were bursting into brilliant bloom, music blared from the windows of the frat houses along Locust Walk, and Frisbees glided gracefully back and forth. A loud, laughing gaggle of sorority girls moving slowly across the Quad was interrupted in mid-conversation by the sudden appearance of the Professor, who blocked their path and informed them—in his best lecture-hall voice—“And may I say, you know we all have to die someday.”

Indeed.

My most enduring memory of the Professor is from the day of my Commencement. Thousands of graduating students strolled the grounds in their black caps and wizard-like gowns, and two lines formed outside of College Hall. One was for berobed new graduates waiting to climb the statue of Benjamin Franklin, to be photographed sitting on Ben’s lap. Some of these statue-climbers were graduate students in their 30s, even a few freshly-minted PhDs. The other queue was composed almost exclusively of undergraduates, eagerly waiting to be photographed with the Professor. Some placed their tasseled caps on the Professor’s head; all wrapped an arm around him as parents snapped away and even helped direct poses.

What I remember most vividly, across a gulf of almost 25 years, is the look on the Professor’s face as the pictures were being taken. Beaming good-naturedly, he looked not only happy but proud—proud of himself, proud of his students, and proud of his university—exactly like most of the professors on campus that day. As I think back to that look, I am convinced that if the Professor was crazy, so were we all.

Unlike the usually boisterous Duck Lady and the theatrically extroverted Professor, the Vent Man was quiet and inner-directed. He was short, slight, and bald, with a fringe of reddish-brown hair around the back and sides of his head. He derived his name from his address: a hot steam vent on the sidewalk of 34th and Spruce, right across from Irvine Auditorium. This steam vent was his perch and post from the crisp, nippy nights of late October to the first warm days of early April.

The Vent Man was a street person’s street person. In contrast to the Professor, who looked as though he slept indoors somewhere from time to time and had some place to keep a change of clothes, the Vent Man lived on his vent. Arrayed every day in the same old pants, soiled wool sweater, and dirt-encrusted checkered sportjacket, his hands and face were darkened by a life outdoors, without access to soap and running water.

Like some sort of drab, unremarkable migratory bird, his initial appearance on the vent was a harbinger of winter, his sudden disappearance five months later the first clear sign of spring. Introverted to the point of being almost completely withdrawn, the Vent Man bothered no one, and no one bothered him. He didn’t beg for money, ask for food, or even seem aware of the people passing by. Nor did the people who walked by him seem to notice that he was there. For all intents and purposes, the Vent Man—like a bush, tree, or shrub—was part of the campus’s landscape gardening.

That changed abruptly one very cold evening in January. I was on my way home from an important conference with my dissertation advisor, which, like all important conferences with my advisor, had been conducted over very dry martinis. Feeling dizzy and seeing double, I stopped by the McDonald’s in the lobby of Children’s Hospital for a hot black coffee to go.

What happened next would surely never have occurred without the salutary effects of gin and dry vermouth. Walking west along Spruce, I made eye contact with the Vent Man. Somehow, for the briefest instant, our eyes locked. Before I knew what I was doing, I was standing in front of him as he lay in fetal position on the vent, gently tapping his shoulder for attention, and then wordlessly placing the cup of coffee in his hand.

As I turned to go, the Vent Man sat up, opened the coffee cup, and with a quiet, intelligent voice said, “Ah… hot coffee is always welcome on a cold night like this.” He sipped it, and said nothing more. I stared at him briefly and continued on my way. From that moment, I understood that no one, metaphorically, is a totally abandoned building. Somewhere, deep inside, a little light is burning where someone is still home.

Looking back, I like to think of the Duck Lady, the Professor, and the Vent Man as three adjunct members of Penn’s faculty, whose role on campus was to teach by example. Their major lesson to me, as I think of them again after 25 years of ups and downs, is that you simply have to take the cards life deals you and play them as best you can—if not to win, then simply to stay in the game. If no one else has written a festschrift for these atypical educators, then I suppose this is it.

Carl Hoffman G’76 Gr’83 is a Tel Aviv-based freelance writer whose articles appear regularly in the Jerusalem Post, and sporadically elsewhere.