Itching for home in a strange new land.

By Jin Lee

“Stay home at all times, touch no one, and never go outside.”

Two weeks after my sister and I immigrated to the United States from China, those were my parents’ orders. A rash had covered my sister’s entire body with blisters, and no sooner did she begin feeling better than her unbearable itching spread to me. The chickenpox: just what my fragile self-esteem needed. As if it weren’t enough to be dropped into a school where we were the only non-white students—to be suddenly illiterate in the face of a strange new alphabet at age 12—now my skin was covered with ugly pink pustules.

It didn’t help that my parents weren’t exactly the bastions of familiarity and comfort I was used to. Before rejoining them in Connecticut, my sister and I had lived with our grandparents in a small village in China for five years. My mom and dad may have been my closest allies, but they seemed more like elderly strangers to me. Especially when they commanded me to do something I’d never in my life considered: stay home from school.

Until that moment, I had never missed a single day. In elementary school in China, I had been the class president who led fundraisers for the national children’s holiday, led class field trips in the spring, and tutored other students. Yet now that I was surrounded by blond classmates I couldn’t tell apart, and boys who pointed and laughed at me, the prospect of hiding in our apartment seemed like a godsend. For the next week, I wouldn’t have to keep my head low and my mouth shut just to survive another day of school, pretending that I was invisible. I wouldn’t have to worry about speaking with complicated hand gestures or trying to do homework that I had no idea how to tackle. I wouldn’t have to do anything but be alone.

In exchange, all I had to do was put up with some physical suffering. But the rewards were worth it. Every morning, after my parents left for work and my sister went off to school, I was once again in charge—free to immerse myself in nostalgic flashbacks to life in China.

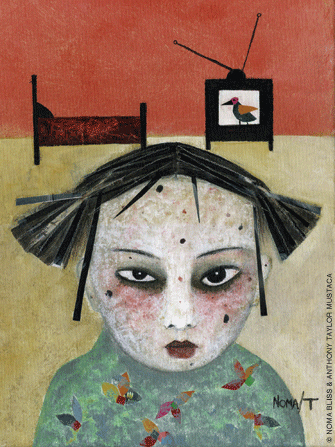

When my stomach grumbled, I cooked Ramen noodles. When my neck was tired, I stayed in bed. And when I needed to distract myself from the infernal itching, I dove into my parents’ collection of Chinese videotapes.

The VCR became my best friend, teleporting me to the side of the world that still felt like home. Accompanied by the sounds of a zither and fiddles, I became Li Ling, a student hopping and walking on a mud road to the elementary school half a mile away. The spring sun threw a golden coat over the rice fields by my side. Birds chirping, kids scrambling this way and that, I bowed to the elders who passed me by and waved to friends sprinting in my direction. Bidding goodbye to our parents, we soon lost ourselves in the usual gossip, jokes, and laughter.

Locked in Connecticut, I knew these sounds and sights painfully well. Now all I had left was Ling’s world on a TV screen to help me forget the nightmares of my first two weeks in this foreign land.

At night, when my family returned, I became Ling. Everyone rushed to feed me, praise me, and make me laugh despite my horrible appearance. With my parents and sister, at least, I could still pretend to be a little Chinese princess. The way things were going, part of me would have been satisfied to suffer the chickenpox indefinitely.

But then something unexpected happened. On the sixth day of my happy quarantine, when most of my lesions had finally crusted over, my sister surprised me with a present. Traipsing through the door after school, she handed me a pink envelope. “This is from your teacher,” she announced.

My jaw dropped. My Chinese teachers would never have given a present to one of their pupils. On the contrary, students were taught to give gifts to their teachers, to show respect and gratitude. This was something entirely new. Heart pounding, I grabbed the envelope from my sister with sweaty hands. I opened the seal and pulled out a “Get Well Soon” card decorated with rose petals and personal notes from my teacher and each of my classmates.

I immediately turned off the television and pulled out my electronic translator. Sitting upright on my bed, I told everyone to be quiet. Carefully poring over every little message, I discovered that they were filled with phrases like miss you and words like love—expressions that are almost publicly forbidden in China.

Year-like seconds passed, as my mind unfolded the latest step in my transition from China to the United States. For a while, my irritating blisters and dreadful, crater-like scars flooded with two streams of tears. The card was the first and the best gift I had received in my new home.

As my blisters continued to fade and the itching let up, I realized that I had been too blinded by self-pity and alienation. My new home might have been foreign, but it offered its own varieties of acceptance and comfort. One thing seemed clear: the time to stay at home and touch no one was over. My week of hibernation and physical suffering had provided me not only a lifelong immunity to the chickenpox, but also a bridge to the next phase of my life.

Jin Lee is a College senior from Connecticut and China.