The Third Reich, seen through the eyes of the American

ambassador and his family.

By Julia M. Klein

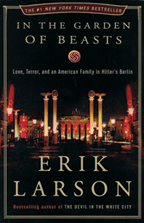

IN THE GARDEN OF BEASTS:

Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin

By Erik Larson C’76; Crown, 2011. $26.

The 12 dismal, soulless years of the Third Reich, bounded by Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933 and the Nazis’ 1945 World War II defeat, have spawned vast libraries, not to mention museums, memorials, and movies. The politics of the era, the military maneuvering, the personalities of the tyrants, the fate of the victims, even the indifference of the bystanders—all have been amply described. And still the flood of stories, heartbreaking and infuriating, continues.

Into this historical maelstrom has plunged Erik Larson C’76 (The Devil in the White City, Thunderstruck, Isaac’s Storm), a master of the novelistic nonfiction narrative, with a tale as yet unfamiliar to most of us. In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin is a Bildungsroman of sorts: a page-turning chronicle of the education of America’s initially naïve ambassador to Hitler’s Germany, William E. Dodd, and his sexually adventurous daughter, Martha. The metaphorically resonant title is an allusion to the ambassadorial residence at the edge of the Tiergarten (literally, “animal garden”), the great urban park in central Berlin.

Dodd, a 63-year-old University of Chicago professor whose chief life goal was to complete his four-volume history, The Rise and Fall of the Old South, was an unlikely choice for such a sensitive post. Indeed, he was selected by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as America’s first ambassador to Nazi Germany only after the more obvious candidates had declined. In Larson’s telling, Dodd, who also had a wife, Mattie, and a grown son, accepted in part because he “saw in this adventure an opportunity to have his family together one last time.”

Dodd’s main credentials—perhaps his only ones—were that he had previously lived in Leipzig and spoke the language, though apparently not with perfect fluency. In other ways, he was startlingly ill-equipped to navigate the cesspool of Nazi Berlin. Though amiable and intelligent, he was disdainful of protocol and concerned more with frugality than the larger political questions facing him. In an atmosphere of violent anti-Semitism that menaced even American citizens, he tried at first to seek common ground with the Nazis by citing the United States’ own alleged “Jewish problem.” So ineffectual did Dodd seem that the Washington-based diplomatic elite took to calling him “Ambassador Dud.”

Dodd’s daughter, Martha, was even more of a misfit. In Chicago, where she became assistant literary editor of the Chicago Tribune, she suffered two failed engagements before making a secret marriage to George Bassett Roberts, a much-older World War I veteran and vice president of a New York bank. The long-distance marriage floundered as Martha began an affair with the poet Carl Sandburg, along with numerous other flirtations.

What was merely shocking in Chicago became foolhardy, even dangerous, in Berlin. The vivacious Martha befriended the foreign press corps and dallied with an unlikely and rivalrous group of paramours, including the French diplomat Armand Berard; the strangely moralistic Gestapo chief, Rudolf Diels; the Harvard-educated, Nazi foreign press chief, Putzi Hanfstaengl; and the Soviet spy Boris Winogradov. Of these, it was Winogradov who was her great love. He inspired her to take a solo trip to the Soviet Union and even to dabble in a bit of soft-core espionage, though Larson assures us that her career as a spy “seems to have consisted mainly of talk and possibility.”

Initially infatuated with (in Larson’s words) “the strange and noble beings of the Nazi revolution,” Martha was slow, like many Americans and Europeans, to discern the moral downside of Hitler’s nationalism. But an increasingly visible undertow of threat and violence, capped by the 1934 Night of the Long Knives, spurred her disillusionment.

Her father would come to feel the same way. In Larson’s words:

Throughout that first year in Germany, Dodd had been struck again and again by the strange indifference to atrocity that had settled over the nation, the willingness of the populace and of the moderate elements in the government to accept each new oppressive decree, each new act of violence, without protest. It was as if he had entered the dark forest of a fairy tale where all the rules of right and wrong were upended.

In contrast, Dodd’s own moral certitude grew. He avoided Nazi Party rallies and eventually shied away from engagement with the regime, resigning himself to what he called “the delicate work of watching and carefully doing nothing.” Larson praises him as “one of the few voices in US government to warn of the true ambitions of Hitler and the dangers of America’s isolationist stance.”

But Dodd was ahead of his time. At the end of 1937, the converging discontents of the State Department and the German foreign office hastened his removal. Back in the States, freed from his ambassadorial shackles, he became “the Cassandra of American diplomats,” speaking out against Hitler’s racial zealotry and expansionist aims.

Based on extensive archival research, In the Garden of Beasts skillfully details the intersection of the intimate with the epic. The great characters of Nazi Berlin—Hitler, Göring, Goebbels, and others—dance through the book, not yet transformed into devils. Larson, as always, is fascinated by historical nuance and the imperfections of human nature.

“There are no heroes here,” he writes, “but there are glimmers of heroism and people who behave with unexpected grace.” He urges us to shed the arrogance of hindsight and remember that “these were complicated people moving through a complicated time, before the monsters declared their true nature.”

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia and a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review.