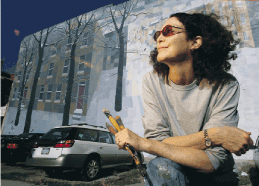

Muralist Jane Golden brings her vision of art as a medium for social change to Penn—and to one wall in the Mantua neighborhood north of campus.

By Kathryn Levy Feldman | Photography by Candace diCarlo

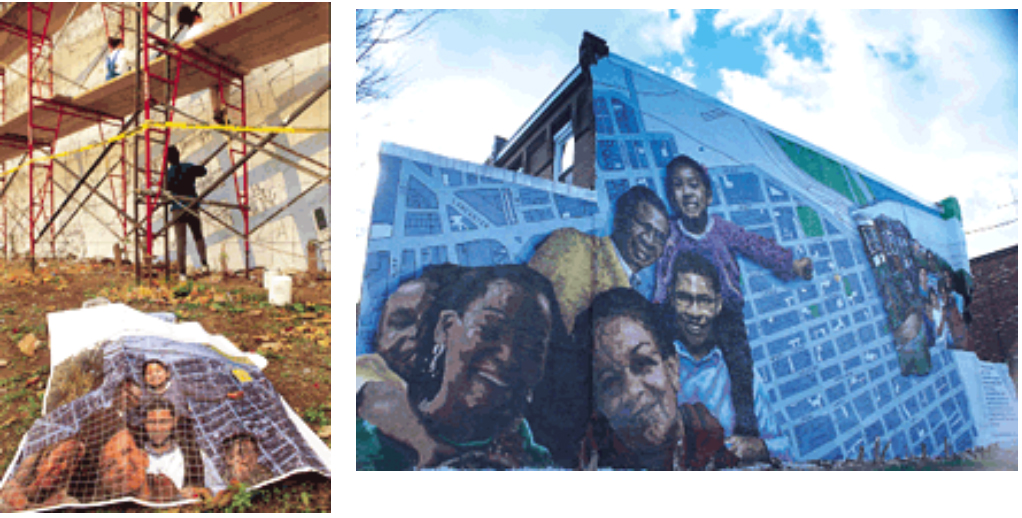

From the third level of scaffolding, approximately 24 feet above the southwest corner of 36th Street and Fairmount Avenue in Mantua, a neighborhood north of the University, Julie Cardillo, a graduate student in painting, is dropping a chalk line to Trish Abbott, an exchange student from University College in London, on the level below her.

“Flick it against the wall to make a mark and then follow up with the ruler,” directs a slim woman from the ground. She sports a shocking-pink head kerchief, paint-spattered blue jeans, and has a cell phone pressed to her ear. “Now move it over 12 inches and do it again. I’ll be right up as soon as they take my call.”

As usual, Jane Golden, instructor of Fine Arts 222/622—aka The Big Picture—and founder and director of the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, is “multi tasking.” As she supervises her 11 first-semester students in the technique of gridding the massive 58 feet wide by 24 feet high wall they are designing and painting for the course she teaches on the history and practice of the contemporary mural movement, she’s on hold with the Streets Department, waiting to complain about the pile of trash that has been accumulating in front of the site.

“You’re doing a great job,” she shouts as she paces back and forth, watching the chalk line progress steadily across the wall. Shaking her head at the discarded sofa cushions, newspapers, and torn trash bags that are encroaching on the lot, Golden tries another tactic. She punches in the numbers of her office.

“It’s me,” she says to the voice on the other end of the phone. “Look, I’ve been on hold with the Streets Department for 20 minutes and I need to teach. I’ve left three messages at [Councilwoman] Jannie Blackwell’s office about the pile of trash in front of 36th and Fairmount. Can you follow up and remind her that I want it removed today? Thanks.”

Two neighborhood residents walk by and overhear the end of her conversation.

“Good luck lady, we’ve been trying to get that stuff hauled away for a month,” one says.

“Oh, it’ll be gone by the end of the day,” the intrepid instructor predicts as she clambers up the scaffolding. “I want the students in my class to become agents of social change, so I’m teaching them the Jane Golden technique.”

Last fall, seven undergraduate and four graduate students became Golden’s second class from Penn to get a hands-on education in the design and creation of public art in one of Philadelphia’s most economically challenged neighborhoods (she previously taught the course in spring 1999). Coursework has included meetings with Mantua community leaders, guest lectures by local mural artists Tish Ingersoll, David McShane, and Josh Sarantitis, and organizing and participating in a community cleanup day at the McMichael School, all toward the design and execution of a mural that meets with the approval of community residents.

It is perhaps telling that the predominant subject in the class’s finished mural is an oversized map of Mantua. For while Golden’s students certainly learned (among other things) to navigate around and between the two distinct neighborhoods of Penn and Mantua, they also discovered that the shortest distance between two points is not always a straight line.

Golden became a mural painter in 1977, after graduating with degrees in fine arts and political science from Stanford University. Her first work was in Santa Monica, a 20 by 100 foot depiction of the once-popular Ocean Pier. (“I called the city every day for three months to let me do it,” she recalls.) It was named a historic landmark in 1984.

The process became “addictive,” she says. “When you paint a mural, you get continuous feedback from people on the street. Each time someone said, ‘Thank you,’ it made my day—and eventually changed my life.”

For the next six years, she painted murals from Beverly Hills West to Los Angeles. Weary of having her work defaced by graffiti, in 1982 she founded the Public Art Foundation in Los Angeles to train kids on probation to create public art. “Mural painting is an incredible way for kids to transition from graffiti to constructive work,” she says. “I [tried] to teach them that there are responsible ways to express themselves.”

Golden was diagnosed with lupus and moved home to Philadelphia to be closer to her family. In 1984, with the disease in remission (where she says it remains), she was hired by the city as artistic director of the mural component of the start-up Anti-Graffiti Network—she calls it “the epitome of a grassroots organization with no money but an incredibly sound philosophy.”

Today, the Mural Arts Program, part of the city’s Department of Recreation since 1996, has an administrative staff of 13 and a yearly budget of $2.5 million. Along the way, the program has garnered a slew of awards, both locally and nationally, as well as significant corporate and foundation support. (Only $800,000 of the annual budget comes from the city.)

In nearly two decades of championing the cause of public art, specifically murals, in Philadelphia, Golden’s mantra has remained the same: Art Saves Lives.

“A mural is so much more than a painting on a wall,” she says. “A mural becomes a catalyst for positive change in a community.”

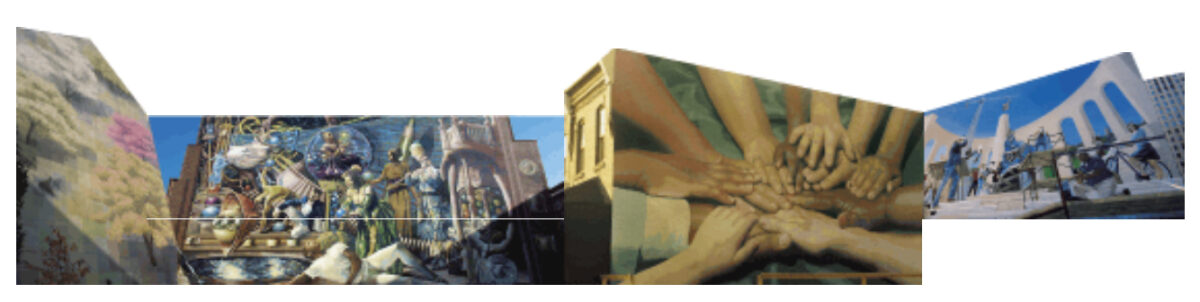

Golden has seen it happen in neighborhoods across the city that have reinvented themselves around the creation of murals. Trash-strewn lots become gardens, drug dealers relocate, graffiti disappears, and residents rediscover pride in their community. But it doesn’t stop there. In the last five years, approximately 2,500 kids have enrolled in her program’s extensive year round art-education components, painting murals or participating in workshops offered at churches and schools, while over the last three years another 5,000 people have participated in its popular tours of Philadelphia’s outdoor murals—the nation’s largest collection of its kind, numbering over 2,000.

Currently, the art-education program for children ages 8-17 operates in 20 sites around the city, including eight recreation centers, four community centers, and eight public schools. This fall, a high-school component, the Mural Arts Corps, was initiated, featuring accelerated design courses, art history, and studio practicum. The program has become a natural component of current Mayor John Street’s “anti blight” campaign, and its outreach program has been expanded into prisons, homeless shelters, and youth-detention centers.

In November, the program moved into a new base of operations, a brownstone at 1729 Mt. Vernon Street that once was the home and studio of the artist Thomas Eakins. For the first time, the program is able to offer a central arts-education workshop for children throughout the city, complete with a computer lab and exhibition space. “This is an unprecedented opportunity,” says Golden.

One reason for the prolonged success of the Mural Arts Program is Golden’s insistence that the process work, as she describes it, “from the bottom up.” She tells her students at Penn that their course, “will explore what that means. There is a certain immediacy to what we do as opposed to the think-tank, top-down approach.”

Another reason is Golden herself—who appears to sleep, breathe, and eat her mission. “She is tenacious, driven, and fabulous. I’ve never seen anybody keep going and moving forward like she does,” says Robert Yermish, chairman of the board of directors of the Mural Arts Program. “Jane is a visionary,” adds David Langfitt, another board member. “She sees in her mind what needs to be done and she does what it takes to implement what she sees. What propels Jane is an unwavering belief in the power of art to inspire, change, and, in some cases, actually heal.”

Midway through her opening lecture—in which she relates the history of the Mural Arts Program—the Penn students are entranced. “It’s a very difficult concept to link art with social services,” Golden concludes. “It’s not an easy process but it is tremendously rewarding.”

The Philadelphia Muses, by Meg Saligman; Peace Wall, by Peter Pagast and Golden; and

“The Comcast Mural,” by Michael Webb.

Linda Watson was tired of staring at the weed-covered lot across the street from her house in the 3500 block of Fairmount Avenue. The city had torn down the abandoned store that had been there about eight years ago, but now overgrown trees, weeds, and trash, not to mention graffiti on the side of the house on the corner, were making it as much of an eyesore as it used to be. If her father-in-law had been alive, he would have rallied the block to do something about it, but now no one seemed willing to take charge.

About six months ago, Watson decided to act. She hired a neighbor to clean up the lot and bought him some paint to cover the graffiti. And then she called the Mural Arts Program and requested an application for a mural. “I had seen other murals all over the city, and I decided it was just what we needed around here,” she recalls. “Something beautiful and inspirational for the kids to look at.”

Just as Watson was putting the finishing touches to her application this fall, there was a knock at her door. It was Jane Golden herself, asking about the wall for her class of Penn students. “It was unbelievable,” Watson says. “Some things are just meant to be.”

It isn’t always so easy. The application that Watson was filling out is step one of a detailed and lengthy process that Golden and her staff have developed over the years to ensure community buy-in and participation.

“What I do could be seen as an invasion,” Golden explains. “We have to be careful to listen to the voices of the neighborhood.”

The program receives 50-100 applications (and many more inquiries) each year, of which about half are selected for new projects. Additional projects are generated by a wide array of community organizations that have established relationships with Mural Arts. Once a mural request is approved, funding is allocated and the community process begins in earnest. Golden and her staff literally knock on doors in the neighborhood, introducing themselves, asking residents what kind of mural they would like to see, and inviting them to attend a community meeting to discuss their ideas.

Golden’s class spent a morning visiting third, fourth, and fifth graders at the McMichael School, located directly across the street from their wall, asking students to draw what they might like to look at. (“You should do a picture of me,” said one third-grader, departing from the recurring themes of sports heroes, American flags, and pictures of the school). They also solicited ideas from such community leaders as Cathleen Watkins, site director of the Mantua Family Center, which occupies the lower level of the school building, and “Mr. Smokey” (the name he is known by), one of the founders of the neighborhood organization, Mantua Against Drugs, and of course, Watkins.

The adults agreed that the mural should be inspirational and should include representations of children as well as community elders. “Whatever happens in the community has to reflect the community,” remarks Watkins.

Back in the studio, painter Tish Ingersoll brainstorms with the class. “You have to remember that it is really hard to paint this wall, primarily because of your time limits,” she warns. “You need to keep it simple.” And inspirational.

“Do we need this to be bright and cheery or are we willing to recognize that their reality is not that way?” wonders Rachel Perloff, a junior majoring in urban studies, who has brought in an architectural study of Mantua done in 1970. The book contains numerous maps of the area that, by coincidence, seem to approximate the shape of the wall.

“The whole map could create the shape of the mural,” Ingersoll observes. Gradually, the concept of a map, with an overlay or window of children and older people evolves. “It’s telling the kids that you can be a piece of Mantua a well as part of the larger community,” Perloff elaborates.

Aside from the relevance of the theme, the design is especially appealing to the non-artists in the class. “I’m good at filling in lines with paint,” jokes Megan McNamee, a senior majoring in art history.

Andrew Evans, a senior majoring in architecture, and Amy Weiss, a graduate student in sculpture, represented the class during the final presentation of the design to the community leaders. “We got kind of fired up talking about the project,” Evans recalls. “We made a few little changes, like making the people bigger, but all in all everyone loved it.”

Certainly that is not always the case—as Ariel Bierbaum C’00 can attest. An alumna of Golden’s 1999 class, she is currently mural-projects coordinator for the program. “I spend a lot of time facilitating meetings between communities and artists,” she says. “The process is not that simple. It always seems like we end up stepping into some sort of a political situation.”

“Every mural has its own story,” Golden says. “Last year we painted 153 and there were struggles in 50 percent of them. We are constantly trying to improve the process so that we can empower the artist as well as the community. It’s an elaborate dance and every year we get a little better.”

One of Golden’s critics, Philadelphia Inquirer architecture critic Inga Saffron, feels the problem lies within the methodology itself. She faults what she calls the “art by committee” approach, saying it is leading to a proliferation of cliché images.

“Desperate for a respite from the surrounding poverty and decay and all the social ills that go with them, these groups tend to select works that reassure rather than provoke—images of happy children, caring parents, and pleasing landscapes,” she wrote in a 1999 column. While Golden admits that there are murals around the city that are not “the program’s best effort,” even those that are artistically substandard have become neighborhood landmarks.

“Sometimes I ask people if we can repaint their mural and they get angry,” she says. “They say, ‘It’s good art to me.’” And while she is willing to let some early efforts gradually fade away, she is adamant about not changing her approach. She agrees with Eva Cockcroft, John Pitman Weber, and James Cockcroft, who write in one of the texts for the course, Toward A People’s Art: “Inevitably, community murals are controversial, for in a world of injustice, exploitation, war and alienation, a formulation of values implies a criticism of that world and the projection of a possible alternative world. Community art becomes a form of symbolic social action and implies further social action.”

“A lot of people look at neighborhoods like ours and think about what we don’t have and we do that ourselves,” says Ruth Birchett, a block captain from North Philadelphia; where a mural called “Tribute to Community Leaders,” painted by Cavin Jones, is located (21st and Dauphin streets). “Mural arts helps us help ourselves. Doing things not to us, not for us, but with us—a revolutionary way of doing business.”

This kind of dynamic between artist and community fits neatly into the goals of Penn’s Community Arts Partnership, chaired by Ira Harkavy, associate vice president and director of the Center for Community Partnerships. It uses visual arts, music, dance, and theater as a medium for community revitalization, improved scholarship and teaching, and strengthening Penn’s relationship with West Philadelphia. In the spring of 1998, Harkavy met with Golden about teaching such a course, stealing a page right out of her book. “At first I said I couldn’t do it because I am so overcommited, “ Golden recalls. “But they were very persistent. I finally gave in.”

The course is cross listed under the departments of Fine Arts and Urban Studies. Julie Schneider, undergraduate fine arts program chair, is thrilled to have Golden on board. “The commitment to the community around us has traditionally been important for this department as well as the concept of exposing students to people in the field,” Schneider says. “Jane is certainly doing both. She is delightful, hardworking, and taking her art and making it part of her political commitments.”

According to Schneider, the course evaluations by students are overwhelmingly positive. “This is one of the best courses I have ever taken,” reads one. “Jane Golden is a treasure. Her course is an enriching part of my college career,” says another.

Back on the scaffolding, it is almost dark and the air has grown chilly. Students and teacher are all cold and tired, but still painting.

Using a computer program, the students first transposed their design onto a 1 inch by 1 inch square grid and then, by hand, transferred each squiggle, square by square, onto the 1 foot by 1 foot grid on the wall. Close up, it looks like a topographical map (“I just drew Madagascar,” jokes Donald Gensler, a second year graduate student and accomplished muralist who is the teaching assistant for the class), but from across the street, the outline of human faces is emerging from the grid of streets. The painting continues, in shifts, whenever anyone is free, including weekends. “We are going to cut a ribbon and have a dedication in December,” Golden assures her students in mid-semester. (The dedication took place on December 15.)

It is time-consuming, strenuous, hard work, but no one complains. “I would do this again,” Evans says.

And so, it turns out, would the community. A pastor from the church across the street has already inquired about a mural, parents have stopped by and asked about art classes for their kids, and the pile of trash seems to have disappeared for good.

It’s all part of the big picture.

Kathryn Levy Feldman is a freelance writer in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. “If you want a Penn connection, my father and husband are both Penn alums and my oldest son is C’05.”