If you were an urban-studies student seeking to master the fine points of mortgage lending and land trusts, you could probably make a few safe assumptions about a class titled “Community Economic Development.” It would probably involve a term paper. You could bet on a written exam. And the homework would be unlikely to include designing a shadow-box inspired by an American surrealist.

Unless, that is, the professor was Andrew Lamas L’81.

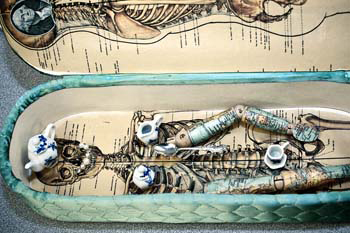

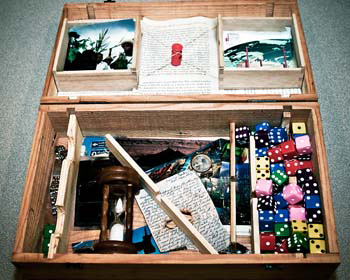

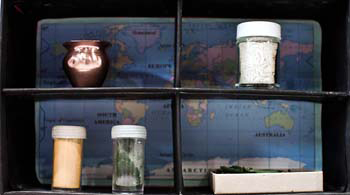

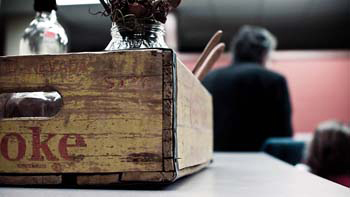

It’s hard to think of a more disparate pair of subjects than urban studies and art history, but this fall Lamas, a professor of urban studies in the College who also lectures in the School of Social Policy & Practice, challenged his undergraduates to embrace the juxtaposition while they delved into topics like sustainable development and alternative means of home-ownership. As they explored the issues raised in class, the students were also charged with creating artworks based on the world-in-a-box constructions of American artist Joseph Cornell.

Cornell, the very profile of a mid-20th-century eccentric, gained fans among compatriots like Marcel Duchamp and Willem de Kooning for the highly personal and obscure assemblages he crafted in the basement of his mother’s unprepossessing house in Queens, New York. Half contemporary collage, half Victorian diorama, his orderly but rustic boxes packed life’s quotidian detritus—feathers, doll heads, bird eggs, hairpins, scraps of ephemera—into exquisite narratives tinged with decay and nostalgia, a remembrance of obscure things past.

For Lamas, the work is about “challenging the conventional.” Art is a great medium to question accepted stances, he says, so why not use it to examine new ways of tackling economic development? The fact that most of his students had never heard of Cornell only added to his appeal as a teaching tool. “Undergraduate education is about discovery: of ideas one has not considered, of new ways of seeing,” says Lamas. “It’s about using original research and creative acts to obtain new knowledge about the world and about oneself.”

The challenge of discovery is what drew senior Julia Luscombe to the class. She’d previously worked with Lamas on an independent project—a documentary on alternative currencies—and had listened with interest as other students raved about his unorthodox teaching methods. “Taking this class with him has really forced me to think about the things we’re studying in my own way, and from many different angles,” she said shortly before the Thanksgiving break. “Hopefully, we’ll come out of the class ready to ‘talk the talk’ that we need to [master in order to] deal with the conventional economy, but we’ll also have the ability to approach problems in ways that aren’t literal or narrow.”

For her Cornell-like box, Luscombe was planning to “build on the theme of renewal” by having edible plants sprouting from objects that represent pollutants. Rachel Squire, a senior urban-studies major, was having a harder time figuring out how to make the assignment relevant. “I really enjoyed seeing the Cornell works at the Museum of Art when we had a field trip,” she said, “but I’m not so sure how good I’ll be at using my right brain!”

That’s the point, said Lamas one Tuesday afternoon in class, after presenting a few slides of Cornell’s work. “When I see a Matisse, I’m in awe, right?” he asked rhetorically, in his slight Southern drawl. “But I don’t then go home and paint one. Because I just can’t do it.”

A young woman took up that thought. “Yeah, this makes me realize that art can be a means of expressing ideas, even if the work’s not traditionally ‘artistic’ and it’s just using everyday objects.”

Another student disagreed. “You keep saying that Cornell’s work is a reaction against the traditional art system,” she challenged Lamas. “But the similarities between his work and the museum world are too strong to be a critique. We’re looking at a box with ‘art’ in it. Isn’t that what a museum is?”

“I like that,” Lamas replied. “But let me push back. Doesn’t every critique to some extent embody the thing it’s criticizing?”

“And museums can be critical of the establishment, too,” seconded a young man. “What about something like the Barnes?”

Such twists and turns are typical of Lamas’ classes, they say. “Taking this class two years ago changed my entire academic trajectory,” remembers senior Jody Pollock, who admits to feeling out of her element as a sophomore in Lamas’ course. “There he was talking about Hegel and Marx, and then we’re reading Francis Fukuyama, and then we’re watching a film about community land trusts. It was a lot, and he pushed us to make connections. He enjoys having students experiment with different forms of media—I think it keeps it interesting and challenging for him, too.”

Absolutely, says Lamas. “I don’t have to be a master of documentary films or comics—projects I’ve assigned in the past—or, now, of Cornell’s work, to assign them,” he laughs. “That’s my strategy. These students are so bright, they can teach themselves. If you can accept that, you suddenly have great freedom in how you teach.”

Lamas’ path to using Cornell as a way of seeing and critiquing was, not surprisingly, circuitous. “This year, in a very unique move, the Penn Reading Project focused on a painting rather than a book,” he says. “I was thrilled by the choice: Thomas Eakins’ The Gross Clinic, widely considered to be the most important American painting of the 19th century.” The spin got him thinking: What about the 20th century? Which artist could be called the most influential? After a few weeks reading up on his old college minor, art history, he was prepared to argue the case for Cornell.

It’s been a thorough immersion. Besides bringing the class to the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see Cornell pieces in person, Lamas also arranged for them to travel to Washington to visit the home of Robert Lehrman C’72, a prominent philanthropist and collector of the artist’s works [“All Things Ornamental,” Nov|Dec 2003]. They also met Howard Hussey, Cornell’s former assistant, at a presentation at the Moore College of Art.

“That was fantastic,” Luscombe says of the Hussey lecture. “I can still hear him responding to a Moore student’s box. He kept asking, ‘Where’s the ego?’ I think that’s what Professor Lamas really wants from us. He wants us to put ourselves into the work we create … he wants us to be integral to the discussion.”

“Are you or are you not a part of the world you seek to study?” asks Lamas in the course description he hands out at the semester’s outset. Thinking inside of the box may provide the answer, at least for this term.

—JoAnn Greco

S L I D E S H O W | Sarah Bloom, Photographer

On December 8th, Prof. Dan Sipe, a professor of history at Moore College of Art and Paul Hubbard, an internationally renowned sculptor and a professor of sculpture at Moore, helped Lamas critique the students work.