Celebrating the art of Joseph Cornell in all its “playfulness and remarkable spiritual resonance.”

EXCERPT:

Alumnus Robert Lehrman is a leading collector of the work of Joseph Cornell, the self-taught artist whose boxes and collages brought him international fame in a career that stretched from the Depression to his death in 1972. That art is gorgeously and comprehensively celebrated in Joseph Cornell: Shadowplay … Eterniday, published to coincide with the centenary of the artist’s birth on Christmas Eve, 1903, in Nyack, New York. Besides essays by Lehrman, Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, the former director of the Joseph Cornell Study Center at the Smithsonian Institution; art dealer, curator, and Cornell-friend Walter Hopps; and Richard Vine, writer and managing editor of Art in America, the 256-page volume features 231 illustrations, 205 in color, of Cornell’s boxes and collages, and the source material—toys, stuffed birds, maps, marbles, clay pipes, shells, newspaper and magazine clippings, and other objects—that he assiduously collected to make them. Included with the book is a DVD-ROM, The Magical World of Joseph Cornell, which provides multidimensional views of the work, along with interviews with scholars and friends of the artist, films made by Cornell, and images of source materials, some never seen before, among other features.

Living with Cornell’s works “has afforded me the opportunity to absorb and respond to their presence in ways not accessible to the scholar, critic, or other interested viewer,” writes Lehrman in the preface. “The works have been good companions, rewarding me time after time with their playfulness and remarkable spiritual resonance.”

In the following pages, we offer some samples of Cornell’s art, along with Lehrman’s commentary.—J.P

JOSEPH CORNELL: Shadowplay … Eterniday

By Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, Walter Hopps,

Richard Vine, and Robert Lehrman C’72

New York: Thames & Hudson, Inc., 2003. $60.00.

1. UNTITLED [AVIARY WITH PARROT AND DRAWERS], 1949

André Breton explained the Surrealist strategy of juxtaposing disparate objects as “the marvelous faculty of attaining two widely separate realities without departing from the realm of our experience, of bringing them together, and drawing a spark from their contact …” Here Cornell has done just that by surrounding a grand, colorful parrot—an embodiment of exotic, exuberant nature, the jungle, the exploits of pirates and adventurers—with humble, domestic, manmade drawers whose blond, weathered exterior exudes a patina of age, with all its connotations of experience, knowledge, and sometimes wisdom.

Filled with promise but something of a tease, the drawers are empty and the lower three tiers do not even open; they are all about possibility. Like the parrot, they suggest both discovery and the unknown. Notions of multiplicity and concealment are paramount. In their mute presence, the drawers hold secret meanings. Although empty, they suggest our compartmentalized thoughts, activities, lives. Cornell wanted his works to stimulate an interactive dynamic of body and mind to encourage our imagination to complete the work. Approaching footsteps can cause the box to vibrate. When we pick it up, the springs above the parrot quiver like a branch in the wild. And if we move the box more quickly, they create a noise like the doppler effect of a distant train, a haunting and romantic sound suggesting travel and exploration and emanating from a vehicle constructed, like this box, of separate compartments linked together.

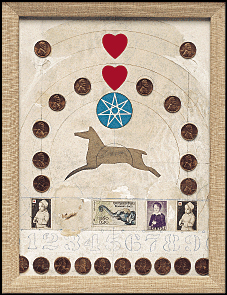

2. UNTITLED [PENNY ARCADE WITH HORSE], C. 1985

At the Hayden Planetarium in New York is an exhibit that depicts the relationships of our planet, solar system, galaxy, universe, and cosmos. It offers an insight into how to appreciate Cornell’s layered works: each level is meaningful in itself, yet gains in significance by its relationship to the whole. The individual parts are like specific “planets”—fixed, clear, identifiable, and knowable. Their relationship creates a “solar system” of visual connections that in turn forms part of a broader galaxy of ideas. These ideas fit into the Cornell “universe,” which embraces attitudes of longing and spirituality ranging across a broad spectrum of nature and science. Together, these images form the Cornell “cosmology.”

The entire spectrum of this cosmology can be found in Untitled [Penny Arcade with Horse]. In this extraordinary small collage, Cornell has combined signifiers of childhood and cosmic notions—a leap of faith suspended in perpetual motion. Concentric rings drawn on the weathered white surface suggest planetary arcs as well as measurements or even a target. Reinforcing and echoing this feeling is the cascading arch of bright shiny pennies surrounding the horse: “planets” reflecting light and circled by penciled orbital rings, which also refer to the innocent but intense childhood pleasures of the penny arcade games of Cornell’s youth. At the center of this “solar system” is the gently arching outline of a leaping horse—an echo of targets in an arcade shooting gallery, but in addition an energized image of grace.

The horse crests a line of stamps, three of children and a central picture of an elephant, a symbol of strength, power, and a reminder of the amazing diversity of nature that can be harnessed by man. Furthermore, elephants are known for their gentleness to their young. An empty space in this line of stamps to the left of center adds an air of mystery and narrative. Was a stamp once affixed or perhaps never chosen? The ghostly traces of glue and empty circles above the vertical lines of three pennies are mute. Trial and error, exploration and experimentation, acknowledged on the surface of this work, form part of its presence. Unbalancing the symmetry of the collage, the missing stamp suggests the random quality of chance (a part of Surrealist strategy), the possibility of surprise, and the power of absence to augment presence.

Contrasting this bit of whimsy, an ordered line of stenciled numbers one through nine below the stamps suggests our decimal system and, more broadly, the mathematics and science underlying notions of nature and wonder. On the back of this collage are images of Pascal’s Triangle, Times Square, and a movie theater and skyscraper on the New York skyline, as well as a photo of a young child. Centered above the horse is a seven-pointed star that also echoes the relationship of science and nature in the universe. Above it all are two hearts—symbols of the love Cornell felt for the world and put into his art.

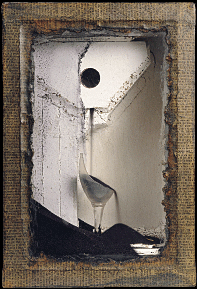

3. UNTITLED [BLUE SAND FOUNTAIN], C. 1954-56

Cornell’s sand fountains are meant to be handled and activated by our participation. Each time I see this fountain in motion, the movement of the sand never fails to be mesmerizing. Seemingly simple but infinitely complex, Cornell’s device is akin to an ordinary sand timer, yet it encapsulates vast worlds and complex ideas.

As the blue sand cascades down from the reservoir at the top of the box, little flecks of white paint skitter across the blue like comets or shooting stars in a night sky. These heavenly bodies have dislodged from the sides of the box through an aging process that Cornell intentionally created by applying repeated layers of paint, each baked in his kitchen oven, to “vintage” the boxes. His Sand Fountains are miniature theaters of time. As the sand falls here, it overflows the cordial glass and, with the undulating movement of a tide, eventually covers the small starfish on the bottom of the box—suggesting both a creature in the deep blue sea and a star in the night sky.

The broken cordial glass (which has a star etched in its side and is also made of sand) additionally is a metaphor for time, which runs over its boundaries. Whether measured by a small timer, the span of our lives, or the seeming infinitude of the heavens, time eventually engulfs everything. The exterior of the box is covered with old French texts from a dictionary of historical biblical and Renaissance figures connecting to other times. The blue-tinted glass on the left front of the box contrasts with the bright white of the back of the box, suggesting the duality of night and day, as well as creating the effect of a veil, yet another metaphor for time. When the sands have run their course (a duration of over six minutes), we are left with a pyramid of blue sand. What better metaphor for a monument made by man to withstand the ravages of time than a pyramid made of sand—here contained in a small box?

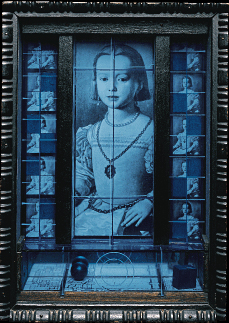

4. UNTITLED [MEDICI PRINCESS], C. 1952-54

This haunting image of Bronzino’s Portrait of Bia di Cosimo de’ Medici in Cornell’s hands has become dream and homage and elegy. The amazing blue of the background in the Mannerist painting must also have resonated with Cornell, for whom blue was the sky, the ocean, the spirit, purity itself.

Cornell shrouded his princess in mystery by placing her in the center of a complex cabinet and behind three different plates of glass, one tinted blue—the color of the night from which she is constantly emerging and the color often used in early films; somehow it evokes memory. The princess is flanked by quartered images of herself in which one or two sections are always obscured by a darker blue, as if in a flickering and incomplete image on film. She seems simultaneously in motion and forever still. The notion exists that part of her, lost to time and irretrievable, is echoed by her hidden image, which is reflected from the back of the blue cube onto a mirror in the lower portion of the box.

Portrayed at a young and tender age, the princess nevertheless displays the formal trappings and gravity of royalty. The fact that she died very young would not have been lost on Cornell, who characteristically in his desire to protect and idealize children, enshrined her spirit in this hauntingly beautiful work. On the floor of the box is an image of the floor plan of the Vatican Museum, a possible linking of art and faith, but also a symbol of the privileged environs that the princess would have enjoyed. The enigmatic blue wooden ball in the lower compartment might symbolize completeness and the self, while also echoing both the toys of childhood and the child herself, moving along paths that she might have traveled in her brief sojourn in Italy as a Medici princess.