In an excerpt from her new memoir, alumna Andrea Mitchell recounts her dustups with power—and love in the time of politics.

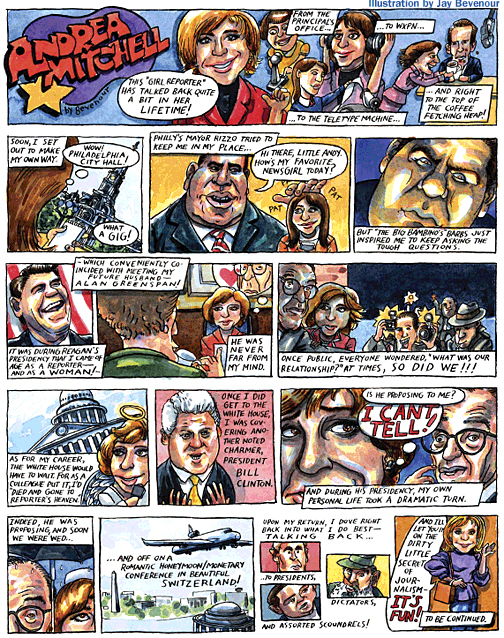

Illustration by Jay Bevenour

Sidebar | INTERVIEW: Off Camera

Frank Rizzo tried to charm her, bully her, hire her, and get her fired. Donald Regan mostly bullied. Hafez al Assad’s security men picked her up and carried her out of a summit-level photo op. Fidel Castro tried evasive action. None of their antics had much effect on Andrea Mitchell CW’67, except maybe to dial up her tenacity another notch. Not for nothing did USA Today once describe her as: “Like a pit bull. With a bone.”

Mitchell’s moxie pulses through Talking Back: … to Presidents, Dictators, and Assorted Scoundrels, her memoir of four hard-hitting decades in broadcast journalism. (“The dirty little secret about journalism is that it’s fun, like being hooked on detective novels,” she writes.) But Talking Back is not all speaking truth to power. Mitchell also observes the changing nature of Congress and the Fourth Estate; ruminates on being female in a testosterone-drenched field; and chronicles her romance with Alan Greenspan, who was named chairman of the Federal Reserve Board during their long courtship.

Now chief foreign-affairs correspondent for NBC News, a post she’s held since 1994, Mitchell got her start in radio—first at student-run WXPN, where she hosted a chamber-music program, interviewed Presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, and covered Election Night at Rockefeller Center. Hired by Philadelphia’s KYW Newsradio as a “copyboy” after graduating from Penn, she soon was covering City Hall and the wildly colorful Rizzo administration, and later the national political scene. By 1977 she had moved to Washington and a local CBS television affiliate, and when the station was sold a year later, she moved to NBC News’ Washington Bureau, her home base ever since. From it she has covered the White House, Congress, and the world.

It hasn’t all been smooth sailing. Her first overseas posting was to Jonestown, Guyana, site of the mass suicide; the horrific experience of the death-site was made worse by the report she filed—which was, she allows, “if not a disaster, completely undistinguished.” (“So who’s the Peruvian handmaiden?” one sardonic NBC script editor wondered aloud, referring to the then-brunette Mitchell.) After a disastrous attempt to describe attempted-assassin John Hinckley on the air, she recalls, the president of NBC News called it “the worst performance he’d ever seen,” and “banished” her from television. But Mitchell, who puts endurance and a refusal to say No at the top of her required attributes for success, was soon back on the screen.

Other apparent setbacks turned out to be blessings in disguise. When she was passed over for the position of chief White House correspondent in 1989 and assigned instead to Capitol Hill, a colleague told the devastated Mitchell, “Sis, you’ve died and gone to reporters’ heaven.” And, in fact, her years covering Congress turned out to be “some of the most interesting and fulfilling” of her remarkable career.

Though she is now something of a media celebrity as well as a Penn trustee, her life could have turned out very differently. Having studied English literature at Penn, her family and professors “fully expected” her to go on to graduate school at Cambridge University, where she had been accepted at one of the women’s colleges. Mitchell herself was not committed to that career path, and a Penn faculty committee judging proposals for a Thouron fellowship sealed her fate. When one of the committee members dismissed her proposal to adapt some literary classics for television as “vulgar,” she decided that, instead of going to graduate school, she would “take a stab at this vulgar profession.”

Here is a selection of vignettes from Talking Back.

—S.H.

In the summer of 1967, Mitchell began working for KYW Newsradio, having been accepted in Westinghouse Broadcasting’s management-training program for young college graduates. After her bosses tried to steer her toward a more traditionally female job in public relations or advertising, she finally told them that she would drop out of the program—if they would give her an entry-level job in the newsroom.

With my Ivy League degree, I had talked my way into a job as a copyboy, which is what desk assistants were universally called in those days. I had to rip reams of wire reports spitting out from the old, clattering Teletype machines, then hang one copy on a nail in the wire room and distribute the others to the anchormen of each hour’s newscast. It helped if you remembered which anchormen liked their coffee black and which took sugar and cream. Most of the men helped me learn the ropes. But some delighted in hazing me as the only woman in the newsroom. As best I could, I tried to deflect or ignore it …

They put me on the shift where they thought I could do the least harm, midnight to eight in the morning. Most of my friends were in graduate school, with more flexible hours. I felt isolated, especially because I had to try to sleep during the day. My social life was nonexistent. Working nights meant walking through the center of the city, crossing Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, to get to my graveyard shift. More than once the police stopped me, until I explained that I was a night worker, not a lady of the night. Although the hours were lousy, they were perfect for an apprentice reporter. The city reflected the national turmoil over race and the Vietnam War, often exploding on my watch …

[Philadelphia Mayor Frank] Rizzo had always enjoyed a fawning press corps, which made me very uncomfortable. As [police] captain and then commissioner, he had fed the newspapers his version of reality, and the leaks greased his climb to the top. His notion of how to handle the few women reporters he encountered was fairly primitive. At first, he tried to charm us. If that didn’t work, he tried intimidation. My verbal duels with him were legendary. At one point, during an antiwar rally, he even had one of his top lieutenants warn me that the civil disobedience unit was doing surveillance on one of my relatives, then a student on the Penn campus. The not-very-subtle message was that I should back off in my coverage of the police. It was frightening, but probably also stiffened my resolve …

As a woman reporter among men, I knew that figuring out how to cover Rizzo as mayor was a special challenge. He was always ready with a cutting comment putting down women, but, paradoxically, that may have helped me to be a better journalist. His barbs only inspired me to ask tougher questions. Not that Rizzo was unique in his patronizing attitude toward women.

James Tate, the man Rizzo was succeeding, was just as bad. At a farewell news conference with Tate, I asked about a major controversy, the city’s failure to win international approval for an international bicentennial exposition. Tate said, “The one thing about not being mayor is I don’t have to answer your questions any longer, little girl.” He might as well have slapped my face. I was the top broadcast political reporter in town, and in an instant I felt like a ten-year-old who had just been dressed down by the teacher.

Rizzo took office and started remaking city government in his own image. KYW carried his news conferences live, and they soon became celebrated confrontations between the bullying mayor and the handful of reporters willing to take him on. On one occasion, The Philadelphia Inquirerreported that the police had shot an unarmed teenager in the back in West Philadelphia. The community was outraged. I called the mayor to see if he would agree to investigate the police. No, he said. “My men are right when they’re right, and they’re right when they’re wrong and they’re trying to be right.”

The mayor called back a few minutes later to complain that his previous comments were off the record. No deals, I said, not after the fact. He was furious, and I was in trouble. After that, he was determined to make my life miserable.

Only years later did I learn from one of my early mentors, KYW’s news director Fred Walters, that Rizzo had called at least once a week to try to get me fired. The complaints even went all the way up to the chairman of Westinghouse Broadcasting, Donald H. McGannon. Fred would tell the mayor to prove that I had been either inaccurate or unfair, and he would take action. Rizzo never produced the evidence and Fred never told me, he said, to avoid any “chilling effect” on my reporting.

I often wonder why I was either naïve or gutsy enough to confront Rizzo as I did. Six feet two inches tall and 250 pounds, he was tough, profane, powerful, and very intimidating. I found myself standing up to him almost as a matter of instinct, only afterward realizing that I was courting danger. At the same time, he charmed a lot of reporters, hiring some of the city’s most experienced newsmen to become members of his cabinet. At one point he even suggested that I could be deputy managing director for housing. At fifty thousand dollars a year, it was a fortune compared to my starting salary of fifty dollars a week. But I knew my job was to be his adversary. It never occurred to me to accept.

Mitchell met her future husband, Alan Greenspan, when she was covering the White House during the first Reagan administration. He was not in government at the time—a situation that would change soon enough.

I’d known of Alan Greenspan since 1983, when he was head of the President’s National Commission on Social Security Reform. Among other assignments at the time, I was covering White House budgets, which included trying to fact-check the fiscal wizardry of Budget Director David Stockman and explain Reagan’s trickle-down economics. On a regular basis I’d question David Gergen, then assistant to the president in the Office of Communications, about the latest budget numbers.

During 1983 and 1984, I hammered Gergen with questions about whether the White House budget assumptions were credible. Finally he said, “Why don’t you ask an outside economist? Learn economics the way you learned about arms control—it’s the next step for you.”

It was smart advice. He suggested I consult Alan, who at the time ran an economic consulting firm in New York.

When I called Alan, with no introduction, he was very helpful. Soon, we were talking fairly regularly, and at some point I asked him to one of those correspondents’ dinners to which reporters invite their sources. As it turned out, Barbara Walters had already invited him, but he said that if I ever got to New York, I should call him for lunch. There was something in the way he said it that prompted me to call Gergen and ask, “Is this guy single?”

To which he replied, “Don’t you know? He’s a really eligible bachelor,” confirming my growing suspicion that Alan was interested in more than the budget.

Still we didn’t get together. Both of us were busy, and we lived in different cities. Finally, in December of 1984, I was in New York to do a year-end report for the Today show, and Alan invited me to dinner. It was December 28, that lovely time between Christmas and New Year’s when the tree is still up in Rockefeller Center, the holiday store windows are festive, and New Yorkers are no longer rushing past each other to finish their shopping. I envisioned doing the Today show live and then taking the rest of the day off to primp for dinner.

But a story broke that day in The Washington Post that Nightly Newswanted me to cover. Instead of preparing for my date, I scrambled to pull together a segment for the evening news. Barely an hour before I was to meet Alan, I raced back to the hotel to change clothes and grab a cab to the restaurant. By then it was snowing. It was also rush hour at Christmastime, and there were no cabs to be had. So I trudged across town to the restaurant, tired, wet, and not very glamorous by the time I arrived at Alan’s favorite restaurant, Le Perigord.

He was already waiting at the table, a pattern that has in fact been repeated in all the years since—Alan waiting patiently, while I finish reporting an unanticipated story. But the moment I sat down with him, the evening was transformed. We connected, talking about music and baseball and our childhoods. I found this shy man known for convoluted explanations on economic trends to be funny and sweet and very endearing. We had such a good time, he suggested extending the evening by going for a drive through Central Park in the snow. That was our first date.

Mitchell had already clashed with President Reagan’s chief of staff, Donald Regan, at the 1985 Geneva summit, after Regan had suggested that women didn’t care about the nuclear-arms race.

Now, a little over a year later, we would go up against each other again, during a night of high drama in the East Room of the White House where the president was finally holding a prime-time news conference to explain the exploding Iran-Contra scandal … As the president faced the press, my colleague Chris Wallace asked about something Regan had told us, that the U.S. condoned Israel’s shipment of arms to Iran. Wasn’t that in effect sending the message to terrorists or states like Iran who sponsor them that they could gain from holding hostages?

Still in full denial, the president replied no, because he didn’t see where the hostage takers had gained anything. He was still unable to accept the linkage between Iran’s ability to purchase the weapons and the Iranian-supported terrorists holding Americans in Lebanon. A few minutes later, Reagan called on me and I followed up on Chris’s question, pointing out that his chief of staff had confirmed that the U.S. condoned an Israeli shipment of missiles to Iran shortly before an American hostage was released in September of 1985. The timing was critical because it was four months before the president had issued a legal directive giving authority to make such arms shipments without notifying Congress.

Standing in the glare of the floodlights, I asked the president, “Can you clear that up, why this government was not in violation of its arms embargo and of the notification to Congress for having condoned American-made weapons shipped to Iran in September of 1985?”

Ronald Reagan said, “No, I never heard Mr. Regan say that, and I’ll ask him about that, because we believe in the embargo.” Caught up in the moment, I asked if he would now assure the American people that he would not “again, without notification, and in complete secrecy, and perhaps with the objection of some of your cabinet members, continue to ship weapons,” if he decided it was necessary. It was the kind of direct, challenging question you might not ask if you had time to rehearse it. Reagan’s answer indicated he had still not accepted the reality of what his rogue national security team had done.

He replied, “No, I have no intention of doing that, but at the same time, we are hopeful that we are going to be able to continue our meetings with these people, these individuals.” Despite everything, he still held on to the fiction that his envoys were negotiating with independent Iranian “moderates” and not the leadership of Iran. I could see panic on the faces of the president’s aides standing in the front of the room. The president had been working off a chronology initially prepared by the CIA, but as it worked its way through the NSC, it had been altered to protect top White House officials, like John Poindexter.

This left Ronald Reagan exposed and vulnerable at the most important press conference of his presidency, briefed with a misleading chronology. It was a particularly explosive combination given Reagan’s penchant for misstating facts even when his staff wasn’t misleading him. As a result, at a moment when he needed to correct the record and show that he was cleaning up the scandal, the president instead repeatedly denied a central element in the case—that Israel had secretly shipped the weapons to Iran for the U.S. The press conference ended at 8:35 p.m. Chris Wallace rushed out to the North Lawn camera position to go live, as I returned to our small cubicle in the White House to start writing a story for the Today show the next morning.

Fifteen minutes later, an announcement over the press room loudspeaker stated that the president was going to issue a written statement clarifying something he had just said. It was unprecedented for this or any White House—a correction, within minutes of a presidential news conference. The mea culpa stated, “There may be some misunderstanding of one of my answers tonight. There was a third country involved in our secret project with Iran.” Reagan was acknowledging Israel’s involvement, mere minutes after his vigorous denials.

Looking at the clock, I realized I had only minutes to get the correction to Chris on the North Lawn before our expanded post-news conference coverage concluded and the network resumed entertainment programming. I’m a good runner, but I broke all personal records getting to the camera position before we went off the air. On my knees so that viewers couldn’t see me, I handed Reagan’s statement to Chris. Without missing a beat, he read it live, adding it was “something that I have never seen before in my years at the White House.”

… But the drama of the night didn’t end with my sprint to the North Lawn. Out of breath from running, I returned to the NBC White House booth to grab a ringing phone. It was Don Regan, yelling and cursing, threatening to ruin my career and have me fired. How dare I embarrass him with the president in front of the entire world? I have never been so frightened, before or since: I could feel my stomach cramp, and stammered that I was only asking obvious questions about points that were in the public record.

The call did not end well. I’ve “talked back” to a lot of powerful men over the years, from Frank Rizzo to the men around Reagan, Clinton, and both Presidents Bush. Until recently, men running for president did not even include any women among their top advisors. It was rare to find women of any real power in the West Wing. Unused to dealing with women as professionals, men in the White House often bullied the women correspondents. But even in that kind of men’s club atmosphere, Don Regan was in a class by himself. He wielded power roughly, and ruthlessly.

Mitchell’s life took an unusual turn when President Reagan asked Greenspan to be chairman of the Federal Reserve Board.

My life had indeed become complicated. In June 1987, I was giving a birthday party for my friend, Reagan biographer Lou Cannon, who at the time was covering the White House for The Washington Post. Almost all of the other guests were reporters, except for Alan and our mutual friend Margaret Tutwiler, then assistant secretary of the treasury, working for Jim Baker. I sat Margaret next to Alan at the foot of the table, and noticed that the two of them were especially jolly, laughing and talking with great animation.

It was only after everyone else had left that I found out why. Alan took me aside and said, “Today, the president called and asked if I wanted to be chairman of the Federal Reserve.” He had, in fact, learned of his nomination in an unlikely setting. His back was bothering him, and he’d been on the examining table at the doctor’s when the presidential call came through. Of course, he’d accepted. Margaret, as an assistant to Baker, had been in on all the details.

We sat up late that night, trying to sort out how this would change our lives. Somehow, our commuting relationship had given each of us a way out of making a full emotional commitment. Now Alan would be moving from New York to Washington, and we would have to think about what we meant to each other, as well as how to handle the possible conflicts of interest.

Our first test came the very next morning, because I now had inside information that had to be kept secret until the president’s announcement. I had to prove I could be trusted, and Alan had to show he was not a risk, despite his ongoing personal relationship with a member of the fourth estate. That day, I sat with Chris Wallace in the Old Executive Office Building, the site of many White House briefings. At the end of a press conference by the secretaries of state and treasury in advance of an upcoming economic summit in Venice, Italy, Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater stood up and said, “The president will be in the briefing room for an announcement at ten o’clock.”

We didn’t see Ronald Reagan very often in the briefing room, so everyone jumped up to rush back to the White House. We needed to notify our networks quickly, so our bosses could determine whether the announcement was important enough to warrant interrupting the soap operas that generate a great deal of advertising revenue. This was all pre-cable at NBC, before we had a twenty-four-hour news operation.

As Chris and I, by then working well together, sprinted across the street toward the White House, he wondered aloud, “What personnel announcement could this be? Perhaps, a new FBI director?” Then he said, “What about Volcker?” because Fed Chairman Paul Volcker’s term was about to expire. I was very quiet.

All of a sudden Chris looked at my silent self and said, “Oh, my God, it’s Alan, isn’t it?”

I couldn’t lie to my colleague, but I said, “If you tell them, Alan’s credibility is in tatters with Jim Baker. He’ll never trust him, or me, for that matter.”

We raced to our little cubicle, where Chris informed our boss that it was indeed important to carry this briefing live, but preserved my secret as to the identity of the new appointee about to be announced. For that, I will always be grateful to him.

When Alan walked in at the stroke of ten that Tuesday morning alongside the president and Paul Volcker, a gasp went up from the briefing room; I wasn’t sure whether to beam with pride or slump in my seat to avoid notice. Years later, Jim Baker told me he and his aides had all been backstage, watching the TV monitors before they walked out, waiting to see if NBC broke the news first. An important test, the first of many more to come.

After that, I sat down with my bureau chief to work out the rules of the road. I removed myself from any economic coverage that would conflict with what Alan does. In fact, even if I weren’t a reporter, he wouldn’t be able to talk shop with me. His work is highly classified, market sensitive, and very complex. I am no economist, and his decision making covers an array of monetary and regulatory issues. I enjoy talking to him about broad philosophical issues, but when it comes to policy, we draw the line.

Certainly, we never would have gotten together if we weren’t already involved in a relationship at the time he was appointed. But neither of us had any idea Alan would ever return to government.

Shortly after Bill Clinton was elected president in 1992, Mitchell asked him about his campaign promise to change the Pentagon’s position on allowing gays and lesbians in the military. He stated his intention to follow through on his promise, which only made things harder for him when the military refused to go along.

Clinton held a news conference on January 29 [1993] to announce his decision to delay the decision for six months. It was contentious. I asked if he hadn’t thought through the practical problems when he made his campaign promise, and what he had learned from dealing with the powerful members of the Senate and the joint Chiefs? He stiffened, and glared. You could always tell when Clinton was angry, because a muscle in his cheek would twitch visibly.

I knew I would not win a popularity contest with the Clintons or their aides. At times, it saddened me, because there was a part of me that wanted to be liked, and despite all my years of reporting, I never quite adjusted to the role of skunk at the garden party. But I responded instinctively to any whiff of hypocrisy on the part of politicians. The Clinton people considered me far too tough and edgy—somehow, they expected campaign correspondents to perform as boosters, not adversaries.

I may have annoyed Clinton, but he hadn’t lost his sense of humor. When USA Today described me in a lengthy profile as “White House watchdog” and a “pit bull,” the president’s press aides photocopied my picture from the newspaper and attached it to every chair in the briefing room. They then took a picture of the briefing room, populated with “Andrea Mitchell” in every chair, and gave it to the president to sign. He inscribed the resulting photo: “To Andrea Mitchell—Here’s my nightmare—They all become clones of you and I vanish under the pressure! One of you is great but sufficient. Bill Clinton.”

Greenspan’s famously oblique speaking manner left more than just economists scratching their heads.

In October of 1996, Alan gave me a surprise birthday party at one of our favorite Italian restaurants and made a lovely, affectionate toast. Few of our Washington friends had ever heard him speak so emotionally or sentimentally. Our close friends Elaine Wolfensohn and Jim Lehrer, who were seated next to each other, thought that he was about to propose in front of everyone. Elaine still says it was Alan’s basic proposal; it was just that none of us, including me, recognized it at the time. We were heading toward marriage, but I’m not sure I realized it, even then. My birthday gift? A diamond ring, though not in a traditional engagement setting. I still didn’t get it.

That Christmas Day, we joined Judy Woodruff and Al Hunt and their children for breakfast and to open gifts, as we always do. Later, back home, we were sitting in the den when Alan asked whether I wanted a big wedding or a small one. Finally, even I understood what was up. That was as close to a proposal as he came. I guess you could call it an evasive proposal, as ambiguous as some of his testimony before government committees. As he once told Congress, if you think you have understood me, you must be mistaken. He thought it was more fun to propose in Greenspeak, as I call his testimony. He swears that he had asked me to marry him three previous times, and that I hadn’t understood what he’d been saying.

By then, Judy and Al and the children had already left for Vail, as they do every year on Christmas Day. We reached them there that night to share our news, but didn’t tell anyone else except family. We had invited friends for dinner later in the week—Kay Graham, Sally Quinn, and Ben Bradlee, among others—on the twelfth anniversary of our first date. With everybody sitting in the dining room, we told our friends we were engaged. Kate Lehrer was at home sick, but Jim was there, and he jumped up and ran to the telephone to tell her. Kay Graham shrieked. No one had imagined that we’d ever become respectable …

We weren’t planning to go on a honeymoon, because we both had too much work to do. But the festivities continued the following evening, when our friends Elaine and Jim Wolfensohn gave us a beautiful wedding reception at their Washington home so we could include many friends who’d not been to the ceremony. The next night, we went to a state dinner, our first as a married couple. I wore a black lace gown, also designed by Oscar [de la Renta], and although the dinner was in honor of the prime minister of Canada, it felt as though we were still celebrating our marriage.

I was seated at the president’s table, next to Dan Aykroyd, and across from Marylouise Oates, a writer and political activist who had been in the antiwar movement with the Clintons in the 1960s. At some point, Aykroyd, the president, and Marylouise all started singing the Beatles song, “I Saw Her Standing There.” Looking around, I tried to reconcile the cultural dissonance of a group of baby boomers—including the president of the United States—singing anthems of our youth, beneath the solemn portrait of Abraham Lincoln in the State Dining Room.

As NBC’s chief foreign-affairs correspondent, Mitchell traveled to many of the world’s hot spots, including the Middle East. In 1994, she flew to Syria with President Clinton as the lone “pool reporter” for the American networks.

Of all the tough leaders I’ve encountered, [the late Syrian leader] Hafez al Assad is the only one who managed to shut me up, much to the amusement of the president of the United States. Bill Clinton flew to Damascus in October of 1994 because of signals from Syria that Assad, Israel’s implacable enemy, was finally rethinking his refusal to consider peace. The president’s first meeting with Assad, nine months earlier, had created an opening for serious contacts …

We were told there would be a press opportunity, but only for cameras. No writers would be permitted. As the only representative for the networks, I told the White House that we would not allow our cameras to cover the meeting without an editorial presence to report the facts and surroundings—standard rules. After huddling with their Syrian counterparts, Clinton aides told us Assad’s men had backed down, but only if I pledged not to ask a question. I made no such promise, as they knew I wouldn’t. Just before I entered the room, the Syrians reminded me once more not to say a word. I simply smiled…

I lined up with the camera crew, mentally rehearsing possible questions to ask. Even if I got lucky, there would be only one opportunity at best. Should I try to get Assad on the record about Israel or terrorism? If I dared to ask a question, what would happen to the camera crew? Assad and Clinton were sitting in armchairs, on either side of a coffee table, not unlike the arrangement in the Oval Office. I waited just long enough to make sure I was not interrupting their small talk, and asked the Syrian dictator why he still supported terrorism—hoping to provoke any kind of response.

The White House and Syrian presidential aides were flabbergasted. No reporter, and certainly not a woman, had ever dared ask Hafez al Assad a question at a photo opportunity. To my amazement, instead of ignoring me, he began to answer, vigorously challenging the premise of my question. As he did later in a joint news conference with Clinton, Assad denied that anyone could name one incident in which Syria had committed a terrorist act. But before he could finish, I suddenly felt myself being lifted off the ground. With the cameras safely focused on the presidents, two burly Syrian security men had come up from behind, grabbed me under the elbows, and were carrying me out of the room. To my amazement, Assad continued to answer my question, but effectively, I was silenced. If I’d protested against what the thugs were doing, I would have interrupted Assad, and ruined the photo opportunity for all of our later broadcasts.

Watching me be ejected so ignominiously greatly amused Clinton, who doubled over with laughter. He later told me that he’d finally found a way to shut me up. Perhaps, but it didn’t last long.

When George W. Bush was sworn in for his second term, Mitchell watched, interviewed, and ruminated over some of the changes she’d seen in her four decades as a journalist.

Inaugurations are also political celebrations for the victors. After the swearing-in ceremony, I climbed onto a flatbed truck to broadcast the Bushes’ progression along the parade route from the Capitol to the White House. It was as close as Washington ever gets to a hometown event, at least in the years since the Redskins won the Super Bowl. I’ve seen so many of these grand occasions: the bittersweet inauguration day a quarter-century earlier when the American hostages were released from Iran, but too late for Jimmy Carter. The departure of Ronald and Nancy Reagan from their “little cottage” on Pennsylvania Avenue after one of the most consequential presidencies in modern history. And Bill Clinton’s exit a dozen years later, following two terms of political triumph and scandal. I have been an eyewitness to all of these histories, personal and political, but in the role of observer, not participant. To me, that remove is still the price of admission for a front-row seat, despite the revolution that has turned politicians into anchormen and activists into bloggers.

Along this journey, I have made sacrifices I sometimes regret, although none so important that I would take the path not chosen. As I was warned so many years ago, this is indeed a course for a long-distance runner. If asked what qualities helped me earn whatever success I have had in this venture, I’d have to list endurance near the top. It is what drove me to the finish line of the New York City Marathon in 1996, two days before the election, and still carries me through assignments in remote regions far from family and friends. But perhaps even more important is an insatiable curiosity about the way other people live their lives—their hopes, disappointments, privations, and triumphs. Those are the stories that inspired me to want to be Brenda Starr, “girl reporter,” imagining an adventurous life then available only to women in comic strips.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from TALKING BACK: … to Presidents, Dictators, and Assorted Scoundrels by Andrea Mitchell. Copyright © 2005 by Andrea Mitchell.

SIDEBAR

INTERVIEW: Off Camera

Midway through the promotional tour for her new book, Andrea Mitchell took time out to talk about her chosen profession—and her chosen spouse—with senior editor Samuel Hughes.

Apart from the obvious reasons—you’ve had an incredibly interesting life and career—why did you want to write this book?

I had grown increasingly concerned about the divisions in our society, and the partisan divide in both politics and journalism. The lack of credibility that politicians are enduring is only equaled by the decline in credibility for journalists. I wanted to take a closer look and dig more deeply into my own career and look at the more recent events, such as the reporting we did before 9/11, before the Iraq war, and try to come up with some answers. I also thought it was a good time to look back at five different administrations that I’ve covered, and recall a time when civil discourse was a lot more civil in Washington and in the rest of the country. And as I went back over my career as a journalist, I tried to come up with reasons why that has all changed …

After so many years of protecting myself behind the barrier that we journalists create so that we don’t hack into our own feelings about issues, I just started scraping that back, and trying to better understand my own emotional responses to things that I’d covered. Some of those feelings had been buried for decades.

Journalists in general like to see themselves as sort of the scrappy underdogs speaking truth to power. There’s obviously a lot of truth to that self-image, but what’s the downside?

We have to be careful not to make ourselves the story. This summer I was in Sudan, in Khartoum [where she was dragged out of a room by Sudanese bodyguards for questioning President Omar el-Bashir about his government’s role in the country’s violence]. And what’s so humiliating about what happened to me in Sudan was that I became the story, and we should’ve been focusing on millions of displaced people in refugee camps. So I kept trying to turn the focus back towards them, especially when we got to Darfur.

As a broadcaster, we always have to be aware that we are on live. To talk back to power, you have to do it within certain boundaries.

But I am really proud of my colleagues—Brian Willams, Ted Koppel at ABC, all of our correspondents in the field who have been talking back to administration officials, especially at FEMA as Tim Russert did, memorably, on Meet the Press with Michael Chertoff—because they are taking journalism to the next level, to advocate for the powerless. And if what we see as ground truth does not match briefings that people in Washington are getting, then we have to say that.

What do you think has been your single most important character trait for your success as a journalist?

I think not taking No for an answer. Being appropriately skeptical and adversarial. I just think we have to really be tough. And enough people are [tough] in journalism. ’Cause we’re really the sole representatives for our viewers and readers and listeners who don’t have the ability to ask the president of the United States a question.

Compare the world of broadcast media for women today to the way it was when you were breaking in.

Broadcasting is much more open today to women on many levels. Not the top level. Women can now get jobs as reporters and producers both in front of and behind the camera. We are still lacking in women who hold the top executive positions and top producing positions. While it is easier for women to get jobs, there are still barriers to rising in the profession.

What were the high points and low points of your journalistic career?

I think my interviews with Castro were one of the high points because I think I got to dig deeper with him than most people who have met him before, and we did various interviews over the years that shed a lot of light on him, on a man who is very hard to approach, very reluctant to go on television these days.

My low point may have been Jonestown, Guyana. Just because of the horror and also because I was so overwhelmed by the challenge of covering it.

You’ve acknowledged the tradeoffs of being married to someone in government. Did you have any concern about writing about your relationship with Alan?

I thought that to do a memoir that was honest, I had to talk about it. I did have some qualms; I tried very hard—and usually successfully—to keep our lives private. I also wanted to acknowledge him, because he has been such an integral part to any success that I’ve enjoyed. He’s so supportive, and so encouraging, and easygoing when things are most difficult. So I wanted people to know the other side of Alan.

How has your relationship with Alan affected your perception of the demands of people in government? Did you get a slightly different sense of them as people?

That’s such a good question, because I’ve seen the sacrifices that people make all the time, and how devoted some people in government can be. Alan’s team, and his colleagues there, and some people I’ve met through him in other agencies, are not only hard-working, but they are incredibly talented, and they are working for a fraction of what they could make in the private sector. I’ve also learned, as any spouse would tell you, that it can be a lot more painful for the spouse than for the public official when you have to face press criticism.

Any advice that you would offer to anyone breaking into the business these days?

I would just wish that aspiringjournalists would commit themselves to real journalism, rather than wanting to be anchors or talk-show hosts. That they learn the fundamentals, so they can really follow in the tradition of broadcasters like [Tom] Brokaw and [Peter] Jennings and their successors.

The other advice would be to getthe best well-rounded education they can, and study everything and read everything and write. Good writing is still reflective of clear-headed thinking. If I had not had a good liberal-arts education, I don’t know that I would have been nearly the journalist that I hope I’ve been.