An exhibition at the National Constitution Center celebrates the multifarious personae of Penn’s Founder with objects ranging from the Constitution of the United States to a pair of cufflinks.

By Julia M. Klein

Sidebar | Feting Franklin

When Benjamin Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1785 after an extended diplomatic stay in France, he didn’t exactly travel light. “He sent home over 100 crates of household furnishings,” reports Page Talbott Gr’80, chief curator of a major traveling exhibition that will mark Franklin’s 300th birthday. “He sent home so much stuff, he had to build an addition to his Market Street house.”

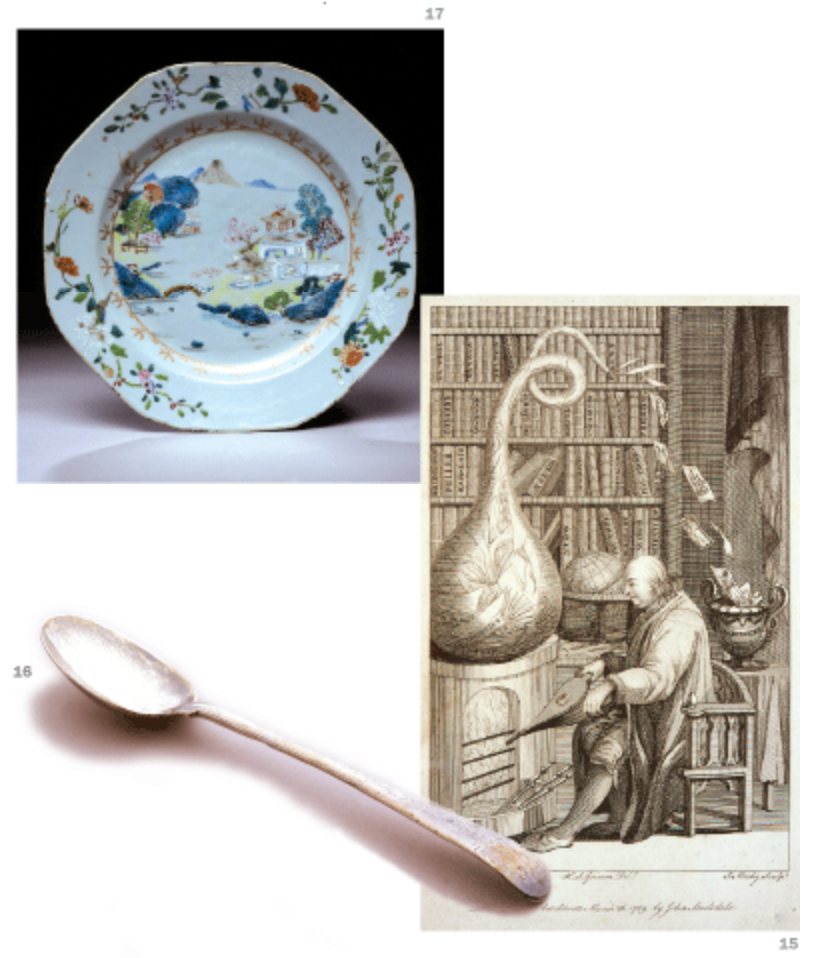

The 55-year-old Talbott, a longtime independent curator, is not a Franklin scholar, but an expert on colonial furniture. So it may be no accident that the greatest revelation of the show, “Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World,” is likely to be the insight it affords into his material possessions: a set of mahogany English Rococo chairs made by French craftsmen, a delicate French porcelain tea service with a Chantilly Sprig pattern, a silver marrow spoon with a family crest, a music stand that may have been designed by Franklin himself.

The exhibition as a whole stresses Franklin’s idealism, including his fervor for scientific experimentation and civic improvement. But Talbott sees no real contradiction between Franklin the idealist and Franklin the committed materialist. “He doesn’t say it’s bad to spend money,” she says, alluding to his famous essay, “The Way to Wealth.” “He says it’s bad to spend money foolishly.”

The timed-ticketed exhibition at the National Constitution Center, which opened December 13 and runs through April 30, is the centerpiece of Philadelphia’s ambitious year-long Ben Franklin 300 celebration. The celebration will include live performances, museum shows, symposia, tours—and 300 parties slated for January 13 through January 17 (Franklin’s actual birthday).

“Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World” is a project of the Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary, a nonprofit consortium composed of the University and two other organizations that trace their founding to Franklin—the Library Company of Philadelphia and the American Philosophical Society—along with the Franklin Institute and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The lead funder, to the tune of $4 million, is the Pew Charitable Trusts. After Philadelphia, the exhibition will travel to St. Louis, Houston, Denver, and Atlanta, before ending its run (in revised form) in 2008 at two Paris museums.

“In our genre—the history museum—there aren’t many blockbusters,” says Richard Stengel, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center. “This is really one of them. Benjamin Franklin is a great brand, one of the greatest brands in American history. And it’s perfectly and wonderfully mission-related for us. The show is really about his civic engagement—and that’s one of the things that we preach.”

The 8,000-square-foot show has more than 250 objects from 76 lenders, including about 30 from Penn. But it also includes evocations of Franklin’s home and work environments, computer interactives and other hands-on activities for children, video animations that relate anecdotes about his life, and images of Franklin in popular culture.

In November, about a month before the show is set to open, Talbott walks a visitor through galleries still under construction, explaining a layout that she promises will be dense with activities. The exhibition, translated into both French and Spanish, focuses on the dazzling multiplicity of Franklin’s personae. It is both chronological and thematic—with sections highlighting Franklin’s overlapping careers as a printer, civic leader, scientist, and diplomat. Visitors will likely emerge awed at his versatility—and, Talbott says, at his sense of humor. “They will see that he was a person capable of laughing at himself.”

In the object-preparation room, Talbott points out rare editions that Franklin cited in his famous Autobiography. John Locke’s Rules of a Society (1720), for example, inspired the formation of Franklin’s Junto, a Philadelphia group interested in civic improvements. It is being lent by the Walter J. and Leonore Annenberg Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Penn. Also from Penn’s rare books repository comes a handwritten household-account book kept by Franklin’s major domo at his household in Passy, France, in 1783-84. “It’s a piece of ephemera,” Talbott says, that his family nevertheless cherished through the centuries. “Unlike the artifacts, which got distributed very fast, I think that they understood that Franklin was a man for posterity in terms of his writings.”

A Wellesley graduate with a master’s degree from the University of Delaware’s Winterthur Program in American Culture, as well as a Penn doctorate in American Civilization, Talbott joined the exhibition team (and took over as associate director of the Tercentenary) in January 2003. By then, a committee of scholars already had developed the show’s themes. Among them was J.A. Leo Lemay, author of a multivolume biography of Franklin being published by the University of Pennsylvania Press and the H.F. Winterthur Professor of English at the University of Delaware. Lemay, who is currently completing the third volume, calls Franklin “the earliest and most thorough of all the revolutionaries.”

As curator, Talbott devised a 79-page, single-spaced outline, many of whose details—like a discussion of the impact of key Puritan leaders on Franklin’s thought—never found their way into the exhibition. But the document served as a roadmap for the long, tortuous process of identifying desired artifacts and working out loans.

High on Talbott’s wish list was a pastel of Polly Stevenson (ca. 1772), the daughter of Franklin’s London landlady, and a close friend who helped care for him in America before his death in 1790. “We knew that it existed, we had seen images of it, but we didn’t know where it was,” says Talbott. “It had disappeared from the face of the earth as far as we knew.” Then, one day, she was contacted by a man named Theodore E. Wiederseim, who owns an auction business in Chester Springs, Pennsylvania, and who knew that a Franklin exhibition was in the works. “Lo and behold,” says Talbott, “he happens to be a descendant of Polly Stevenson—and he had the pastel. And he was willing to lend it.”

Other key loans are five of America’s founding documents, all signed by Franklin. In addition to the Constitution and (at the Constitution Center) Jefferson’s own manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence, they include the less well-known 1754 Albany Plan of Union (a proposal for a legislative body that was ultimately rejected by the colonial legislatures), the 1778 Treaties of Amity and Commerce (which secured France’s material support for the American Revolution), and the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which spelled out the terms of American victory.

Installing these rare documents—from the National Archives and Records Administration, the American Philosophical Society, the Library of Congress, and other lenders—at each venue is a particular challenge. Different copies are being used at different sites for conservation reasons, and, Talbott says, the lenders “don’t want to truck it by a shipper. They want to bring it themselves—with a guard.” In most cases, a curator must supervise both the installation and removal.

Essential to the mounting of the exhibition has been the cooperation of Franklin’s descendants. With his common-law wife, Deborah Read, Franklin had a son, Francis Folger, who died at 4 of smallpox, and a daughter, Sarah, called Sally (1743-1808). He also had an older illegitimate son, William (1731-1813), whose mother has never been identified. It is this son, the onetime Royal Governor of New Jersey and a Loyalist during the American Revolution, from whom Franklin was famously estranged. Talbott says she is convinced that some of William’s descendants survive, but only Sally’s are known to historians.

One of them, Ted Molin, a lawyer and financial services company officer who lives in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, has lent what Talbott calls “a very important portrait” of William Franklin. Attributed to the English painter Mather Brown, ca. 1810, the portrait is part of a “matched set” that includes a portrait of William’s second wife.

The exhibition’s first section, “Character Matters,” features another important family loan: a massive 1763 Bible sent by Franklin to Sally from England, and printed by Franklin’s friend, James Baskerville. On the title page Franklin has inscribed his daughter’s name. “This is the family Bible,” says Talbott, “and it has the names of all the descendants in it.”

Section II, “B. Franklin, Printer,” displays a 1720 printing press used by Franklin in London, as well as a portrait of Franklin’s son Francis and another of his wife, recently cleaned as part of the Tercentenary’s $600,000 conservation project. Franklin, who advocated the American cause in England and France, was separated from his wife (who feared the transatlantic crossing) for about 14 years in all.

But that doesn’t mean he was stepping out on her, Talbott says. “He had one child out of wedlock, and that’s it. And he was a man who had a reputation of being charming and flirtatious, but he was not a gadabout,” she adds, with some heat. “Not in the least. There’s nothing to substantiate that he had affairs.”

Not that Franklin was an ideal family man. “I think that was a weakness in his character,” she says, citing his “dysfunctional” relationship with his son, William. “We’re not trying to tell the story of a perfect [person]. In fact, we’re trying to tell the story of a real human being—a man who is accessible, a man who is just like you and me.” The exhibition also makes clear that Franklin owned slaves for a while, though he ultimately supported the abolitionist cause.

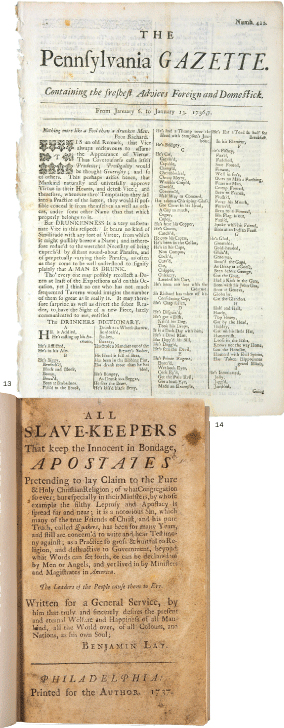

(13) The Pennsylvania Gazette, no. 422, January 6-January 13, 1736, owned, edited, and printed by Franklin from 1729 to 1748. (14) “Benjamin Lay, All Slave-Keepers That keep the Innocent in Bondage” (1737), the second of two early abolitionist tracts printed by Franklin.

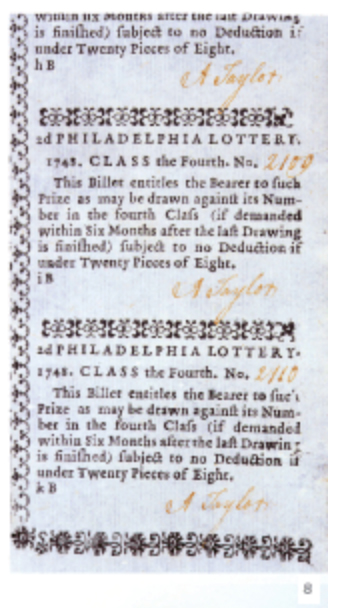

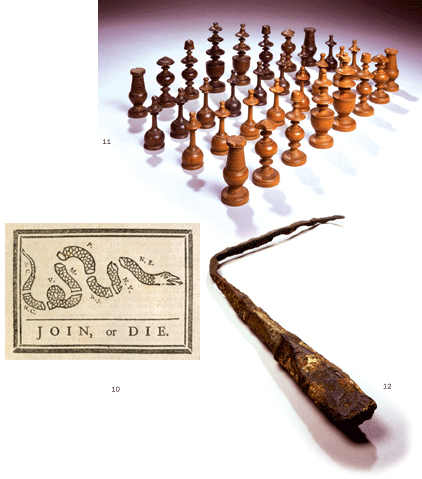

The third section of the show, “Civic Visions,” focuses on Franklin’s Junto and its “conception of community building,” Talbott says. It discusses Franklin’s role in founding such local institutions as Pennsylvania Hospital, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the city’s first fire company, and the University—but without, Talbott says, being “Philadelphia-centric.”

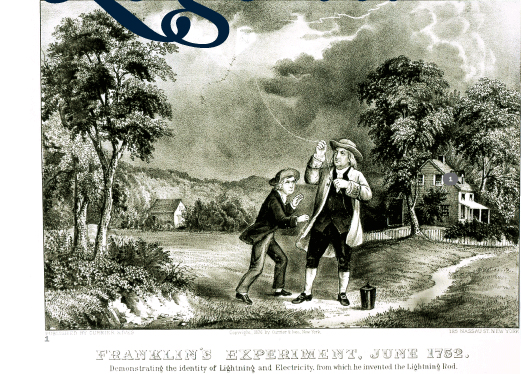

The “Useful Knowledge” section depicts Franklin as one of the preeminent scientists of his day, with a re-creation of a “gentleman’s laboratory,” along with Franklin’s own lightning rod and other scientific equipment. A 25-foot-long ship “environment,” allowing visitors to try Franklin’s method of charting the Gulf Stream, didn’t fit in the galleries, so it will be set up in the Constitution Center lobby.

In “World Stage,” visitors witness Franklin’s humiliation in London in 1774, when he is accused of releasing letters from Massachusetts’ Royalist governor asking England’s help in subduing the disobedient colonials. “This is going to be a particularly visceral experience,” says Talbott, as visitors stand beside a full-sized Franklin statue and listen to a scathing address by the English solicitor general. “That was the turning point for Franklin—when he became truly a revolutionary,” she says.

(16)Silver spoon (London, 1771-72) by Elias Cachart, owned by Franklin. (17) Hard-paste porcelain export plate (Chinese, 18th century), owned by Franklin. All from the Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Photos by Peter Harholdt.

Finally, in “Seeing Franklin,” visitors also will be able see themselves—literally and perhaps metaphorically. A 12-foot-wide, photo-sensitive pair of glasses will enable them to watch images of Franklin morphing into their own self-portrait. “That,” says Talbott, “is the stunning final moment,” as exhibition patrons are challenged to identify with Franklin’s legacy and make it their own.

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia who writes for The New York Times, Mother Jones, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and many other publications.

SIDEBAR

Feting Frankin

Benjamin Franklin turns 300 on January 17, 2006, but events in honor of his tercentenary are happening year-long. The celebrations were kicked off in October with a reenactment on a Market Street returned to its colonial days of 17-year old Franklin’s arrival in Philadelphia—an event memorialized on Penn’s campus in the 1914 sculpturre of the young Franklin by R. Tait McKenzie that stands outside Weightman Hall. Some events appear below, with Penn events highlighted. A full listing can be found at www.benfranklin300.org.

Ongoing

- Ben Franklin: In Search of a Better World. The largest collection of Franklin materials ever assembled, this centerpiece exhibit of the tercentenary celebration “will immerse visitors in Franklin’s world and leave them inspired by his example.” The National Constitution Center, through April 30. $9 adults, $7 seniors, children, students, and active military [see main story for more information].

- Franklin…He’s Electric!Visitors to this exhibit can explore the scientific contributions of the man who invented bifocals, swim fins, and musical instruments. The Franklin Institute, permanent exhibit. $13.75 adults, $11 seniors and children.

- For the Education of Youth. Maps, drawings, and documents reveal how Franklin’s proposal for higher education turned into the reality that is the University of Pennsylvania. College Hall, through June. Free.

- Franklin Footsteps Walking Tour. Explore Franklin’s neighborhood, and learn about his civic involvement, his roles in government, and how he came to invent the four-sided street light. Leaves from Franklin Court, April 1–June 30 and September 3–October 31 Saturday and Sunday at 2pm, July 1–September 2 daily at 2pm. Free.

- Franklin Lunch. Enjoy a three-course lunch priced at $17.06 in honor of Franklin’s birth year. Le Castagne, $17.06.

January

- Franklin Biographers: A Reunion. Jim Lehrer of PBS’s Newshour joins three prominent Franklin biographers in conversation. The National Constitution Center, January 8. Free, reservations required.

- 7-up on Ben. Seven members of the Penn community will talk for seven minutes each on what Benjamin Franklin means to them. Kelly Writer’s House, January 17. Free.

- Institute of Contemporary Art Project Space: Brian Tolle. A special installation commemorating Franklin draws on artist Brian Tolle’s collaboration with local historical archivists and fabricators. Institute of Contemporary Art, January 17 – March 26. $6 adults, $3 seniors, students, artists, free to children and Penncard holders.

- Ben Franklin: Unplugged. In an energetic and funny theater performance, monologist Josh Kornbluth sets off on a journey to uncover the mysterious relationship between Franklin and his son. Plays & Players Theater, January 10–22. $15–$45.

February

- Birthday Party for Benjamin Franklin. A Philadelphia Orchestra concert explores Franklin’s passion for music. The Kimmel Center, February 4. $7-$44.

March

- Franklin Court. The Pennsylvania Ballet brings Franklin’s inventions to life with dancers personifying swim fins, bifocals, and electricity. The Academy of Music, March 3 – 11. $10 – $105.

April

- Franklin Symposium.A panel will discuss Franklin’s ideas on education, followed by a performance of music from his time by Tempesta di Mare, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s annual dinner and speaker award ceremony. Panel at Van Pelt-Dietrich Library (free), performance at the Penn Museum, April 4. Panel free.

- The Medical World of Benjamin Franklin.This exhibition examines Franklin’s contributions to medicine as well as his own challenges as a medical patient. College of Physicians of Philadelphia, April 8–June 30. $10 adults, $7 seniors and students.