Three classic cars.

By Witold Rybczynski

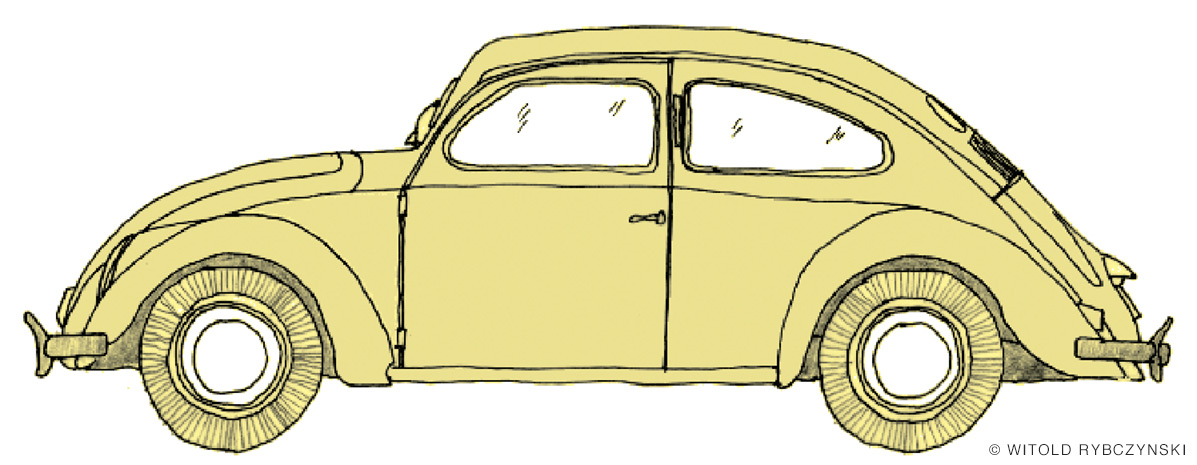

My first car was a Volkswagen Beetle. The design was already 30 years old—seven years older than I—and production would continue for another 36 years, making it the world’s longest-running automobile model. I bought mine in January 1967. After college, I’d worked and saved my money, and, as many young architects had done before me, I set out on a European grand tour. My VW was seven years old, bought for $300 in Hamburg, where the freighter on which I had booked passage from Quebec City berthed. The car carried me and a friend without a hitch from Paris to Valencia (where it was stolen, but that’s another story). Nine hundred miles. I’d never driven a VW, but the controls were simplicity itself. The enameled metal dashboard was dominated by a large speedometer that included an odometer, three warning lights—blue for the high beams, red for the generator, and green for low oil pressure—and an indicator for the flashing turn signal lights, which by 1960 had replaced the original semaphore indicators. There was no temperature gauge because the engine was air-cooled. There was no gas gauge, either—when the engine stuttered, it meant the tank was empty, which required flipping a lever below the dash to access the reserve—about a gallon, good for roughly 40 miles. The dashboard included two unidentified white plastic pull knobs: the one on the left controlled the headlights; on the right, the windshield wipers. I believe that there was also a choke. The turn signal was controlled by a stalk on the steering column, and the headlights were dimmed by depressing a floor switch. There was an ashtray, although no lighter. A knurled knob on the floor beside the stick shift controlled the heat, which came from an exchanger surrounding the exhaust pipe. The first time I stopped for gas, I looked in vain for the gas cap—I found it under the hood, which was actually a trunk, since the engine was in the rear.

I was reminded of my old VW the other day when my friend Jerry gave me a ride in his new Prius. Instead of a speedometer and traditional gauges, there was what Toyota calls a Multi-Information Display, an LCD touch screen swimming in icons, graphics, and numbers. The colorful array, which reminded me of a pinball machine, conveyed a range of technical information such as tire pressure and fuel consumption, as well as navigation and entertainment information and extraneous details such as time and date and whether a door was open. Somewhere, there was a number indicating the car’s speed. The cost of adding digital information is minimal, and I had the impression that the designers had simply piled on the bells and whistles. Perhaps that’s why Jerry’s owner’s manual was almost 800 pages (compared to 90 for a 1960 VW), 20 pages just on operating the lights and wipers. Jerry told me his dealer offered a course for new owners on how to manage the complicated display. No doubt one got used to the busy flat screen, but I would miss the elegant minimalism of that old VW.

The car I bought in Hamburg had distinctive oval German export license plates, and an international registration sticker marked with a D, for Deutschland. As I drove through Holland on my way to Paris, more than once when asking for directions I received dirty looks, especially from older persons for whom the wartime German occupation was a living memory. And, after all, my car’s godfather was Adolf Hitler himself. Opening the 1933 Berlin Motor Show as the newly appointed reich chancellor, he had announced a national policy to motorize Germany, which despite having invented the automobile a half century earlier, lagged other European countries in car ownership. Hitler called on the auto industry to produce an affordable people’s car, a volkswagen.

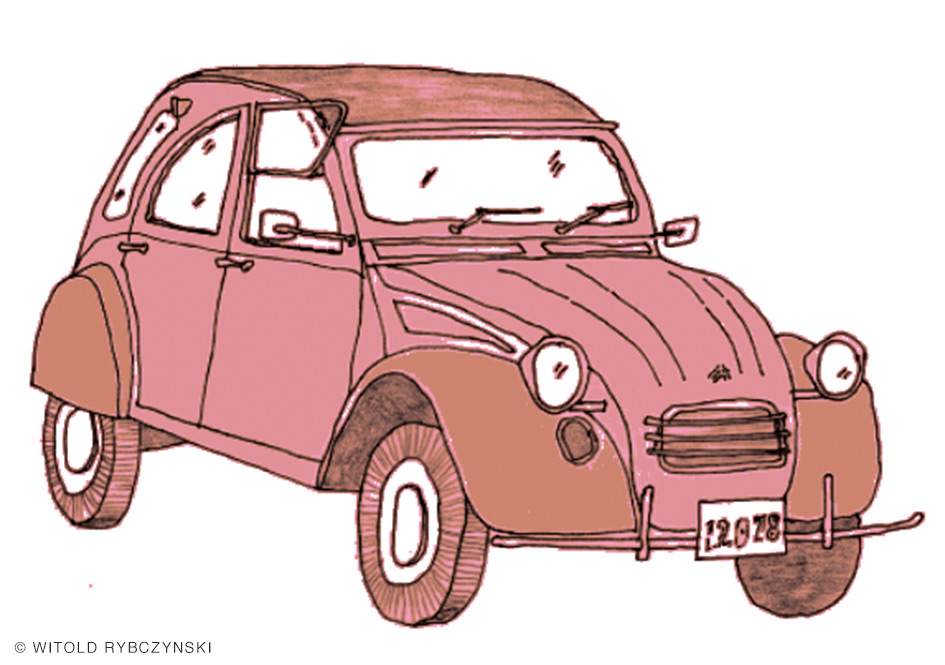

My first new car was a Citroën 2CV, which the French call Deux Chevaux, or Two Horses. It wasn’t actually two horsepower, although it sometimes felt that way. CV stands for chevaux-vapeurs, or steam horsepower, and 2CV refers to a tax category, because France, like most European countries, levies an annual road tax on car owners based on engine displacement. My car, bought in 1969 when I lived in Montreal, had a two-cylinder engine that produced 12 horsepower. That’s pretty small—half as powerful as a Volkswagen and smaller than many motorcycles. It meant a top speed of about 55 miles per hour if you were lucky; less in a headwind. The day I bought the car, I gave a friend a ride, and driving across Mount Royal I had to keep downshifting as the car went slower and slower. Never mind, I loved my fire-engine-red Deux Chevaux. The Beatles’ Abbey Road album was released that year, and in honor of their song “Here Comes the Sun,” I painted a stylized yellow sun on the trunk lid. Well, it was the sixties.

What appealed to me about the Citroën? I like cars, although I’m not particularly adept mechanically. I can change the oil and replace spark plugs or a fan belt, but that’s about the limit of my competence. It was the design of the 2CV that attracted me, the inventive way that each problem was solved in a distinctive, dare I say Gallic, fashion. For example, the car rode high and had a suspension designed to produce a smooth ride over bumpy back roads. This softness produced an alarming (but quite safe) tilt when cornering, and also meant that when there were passengers in the back seat, the rear of the car sank down. If it was nighttime, that made the headlights point up instead of illuminating the roadway. Pas de problème: a knurled knob under the dash rotated the bar to which the headlights were attached, lowering their angle. To reduce costs and keep the doors thin, the front windows did not roll down, but had a hinged lower portion that swung up, enabling the driver to make hand signals (the original 1948 version had no turn indicators) and pay tolls. An openable horizontal slot beneath the windshield extended the full width of the car and provided natural ventilation—no fan required. The lightweight seats resembled lawn chairs—thinly padded cloth over rubber bands stretched between tubular steel frames. The seats were easily detachable, and with the two rear seats removed, cargo space increased dramatically. In addition, the seats could be used as lawn chairs when picnicking or camping. The roof was fabric, because that was cheaper and lighter than metal—and the fabric could be unrolled, like a window blind. One evening, I inadvertently left the roof open and rain left an inch of water in the car; the designers had thought of that, too, and provided rubber drain plugs in the floor.

The controls were as simple as in my old Volkswagen. The speedometer and gas gauge were in a small pod behind the steering wheel, and instead of a dashboard there was a convenient shelf. The gearshift was a lever protruding over the shelf. The steering wheel was tubular steel, nothing fancy; no central horn button—instead, you beeped by pushing on the stalk that controlled the headlights. The sole luxury, installed for Canadian export models, was a large gasoline-fired heater in the engine compartment that instantaneously blasted hot air into the car.

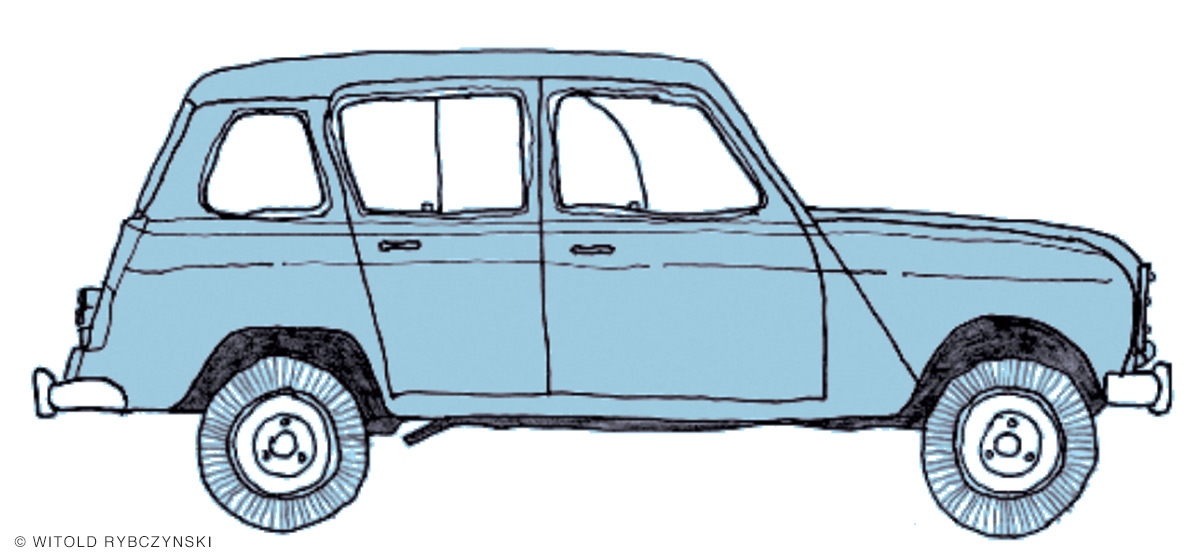

“Have you ever driven a Quatr’elle?” the front-desk clerk at the car rental agency asked me. He gestured to a small light blue car standing outside. I had to admit that I hadn’t—I wasn’t sure what a Quatr’elle was. “Going far?” he asked. “Athens,” I responded. He looked at me for a few seconds, then shook his head, gave a Gallic shrug, and went back to filling out the paperwork.

It was June 1964, and I was in Paris, embarking on an eight-week architectural road trip with a classmate. Ralph and I had met in the fourth year of our course at McGill University, worked together on class projects, and become friends. He was a Montrealer, a year older than I, and I deferred to his judgment in many matters, including the organization of the trip. Ralph had located youth hostels, looked into car rental agencies, and researched the itinerary. Our route would take us through Switzerland, across a corner of Italy, down the Dalmatian coast, inland across Yugoslavia, and south to Greece and Athens. In all, about 1,800 miles.

We loaded our bags into the back of the car, which had a large hatch. It was decided that today I would drive and Ralph would navigate. I got in the car and had a moment of confusion. I had learned to drive with a stick shift, but where was it? Not on the steering column, as in my father’s Vauxhall, and not on the floor. Ah, it must be that lever with the white plastic knob that was sticking out of the dashboard. There was a large speedometer, stalk controls on each side of the steering column, one of which turned out to be the horn, and a bunch of toggle switches for lights and heating that I would figure out later. A helpful mechanic leaned in and explained the operation of the mysterious gearshift, and we were off. We first had to get out of the city, and I remember zipping up the Champs–Élysées and whizzing around the Place de l’Étoile, as it was then called. “Perhaps we should slow down a little. No need to drive like the Parisians,” Ralph observed in his usual calm manner. I eased off the accelerator.

The car I was driving was a Renault 4L (pronounced quatr’elle). The L stood for “luxe,” although there wasn’t much luxury to be seen in the rudimentary interior—no fancy finishes, mostly painted metal, sliding instead of roll-down windows, a rubber floor mat. And who needed a radio? The hammock seats, made out of padded fabric supported by curved steel tubes, were surprisingly comfortable. So was the car’s soft ride, heeling over in corners and gliding over bumps. I didn’t give this much thought as we drove out of Paris, but the suspension would serve us well on the rough back roads of Yugoslavia. In fact, the Quatr’elle was a proficient off-road vehicle, and would place second in the demanding 1979 Paris–Dakar rally, right behind a Range Rover.

“Not too many frills and a workhorse” was how Ralph later described the car. The Quatr’elle was Renault’s answer to the Citroën 2CV. When Pierre Dreyfus (1907–1994), the new chairman of Renault, launched the project in 1956, he described what he had in mind: “I want a versatile car, one that’s urban and rural at the same time, and one that suits the needs of everyone. Call it the blue-jeans car.” Like the 2CV, the Renault 4 was a four-door four-seater with a front-mounted engine driving the front wheels. The four-cylinder engine, a reliable Renault standby, produced 27 horsepower and a top speed of about 55 miles per hour. The engine was water-cooled, but to minimize maintenance the Renault engineers had devised an ingenious sealed cooling system that never needed topping up, and unlike many cars at that time, the Renault had no lubrication points. The car had a soft and supple suspension, and rack-and-pinion steering. The roof was steel. Instead of the Citroën’s rounded body, the utilitarian Renault was boxy—actually, two boxes: a big one for the people and a small one for the engine. Less character but more space. Despite being eight inches shorter than a 2CV, the boxy Renault 4 had more room, and removing the back seat created plenty of storage space. Access to the rear was by a top-hinged glazed hatch, making the Quatr’elle arguably the first hatchback. The design lacked the Deux Chevaux’s quirky charm, but it had the schematic simplicity of a toy car in a children’s coloring book.

The Quatr’elle had been on the market for four years when we rented it, and Renault would sell 8 million of this unprepossessing little car worldwide by the end of its run in 1994, making the Renault 4 the world’s number three car in terms of total production, just behind the Ford Model T and the Volkswagen Beetle. This success was due in large part to the car’s adaptability and versatility. The Renault 4 wasn’t a car to impress the neighbors or play boy racer. It was for transporting families, large dogs, and bags of groceries. And two wide-eyed architectural tyros.

It took Ralph and me almost three weeks to reach Athens. We were not in a hurry, and we made many stops along the way, including visits to the world’s fair in Lausanne, Diocletian’s Palace in Split, the medieval monasteries of Meteora, and the shrine of Delphi, the first of many ancient sites. We spent two weeks in Greece, and on the strength of reading Zorba the Greek I made a four-day side trip to Crete. The return journey took us across the Adriatic and up the Italian boot, with a visit to Pompeii and extended stays in Rome and Florence. The last week driving through the French Riviera was hurried, with brief stops in Cannes for a dip, and Marseille to see Le Corbusier’s famous Unité d’habitation. We took the motorway up to Paris, arriving in the city the day before we were due to return the car. The little Renault had performed admirably, especially on mountainous backcountry roads. “Driving on dirt is a little like driving in powder snow,” I noted in my journal, adding with the insouciance of youth, “I nearly drove off the road once or twice, which could be serious when there is no guard rail and a hundred-foot drop.”

Witold Rybczysnki is the Martin and Margy Meyerson Professor Emeritus of Urbanism. Adapted from The Driving Machine: A Design History of the Car by Witold Rybczynski. Copyright © 2024 by Witold Rybczynski. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.