The satisfaction of three sentences, a signature, and a stamp.

By Lisa S. Greene

There were no postcards at the Philadelphia airport.

I had left a rabbinic conference in time to pick up a snack and postcards before my flight, but amidst the Phillies, Eagles, Flyers, and Liberty Bell paraphernalia, I could not find a single postcard. A wave of unsettledness set in—what did this mean for the state of humanity and the future of the written word?

It’s not too much to say that postcards define me. I always write to my kids when I travel. Sitting down to write on the road—or even downtown on my day off—provides a mindful practice of reflection on conversations, art, and history. And sending postcards strengthens my connection with friends across the map.

I endured the pandemic by writing at least one personal note each day, reaching out like the elusively extended hands in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling. Late at night I’d sit at my desk, the stillness allowing me to sense who I wanted to connect with. I’d pull out a fitting card, write, address, and stamp it, and place it in the mailbox before heading to bed, knowing that despite the world tumult, in this moment, there was calm.

There’s a deep family history behind my need to write. My grandparents wrote longhand letters, and my parents were prolific postcard and letter writers. When Dad traveled—or even just popped into Manhattan for a meeting—he wrote to us in his slanting lefty script reporting on who he ran into on Lexington Avenue. When my sister Jackie and I went to summer camp, Mom sent postcards in her kindergarten-teacher print—“At the Whitney with Barbara and Joan,” or “In Maine with Harriet”—messages light in content but big on love. Finding Mom and Dad’s cards today, often as bookmarks in favorite volumes, summons their faces and voices, and reminds me how they encouraged us to look out at the world to see and learn.

When I was little, Mom started placing postcards we received in a metallic box. I wonder now if she and Dad asked their globe-trotting friends to send Jackie and me cards, or if that was just what everyone did back then. Last summer, after Mom died, Jackie and I packed up the old house with our cousin Amy. I found the box. Memories came rushing back. Before me again were Uncle Joe’s mystery cards, signed with a question mark. Here was one from Amy’s late father, my Uncle Fred—a professor who made frog noises with his hands. On a postcard depicting Lady Liberty, he had signed a note to me using our childhood nickname for him: “I am in New York…Who is the lady on this card? Amy once called her the Liberty of Statue. Love, Froggy.”

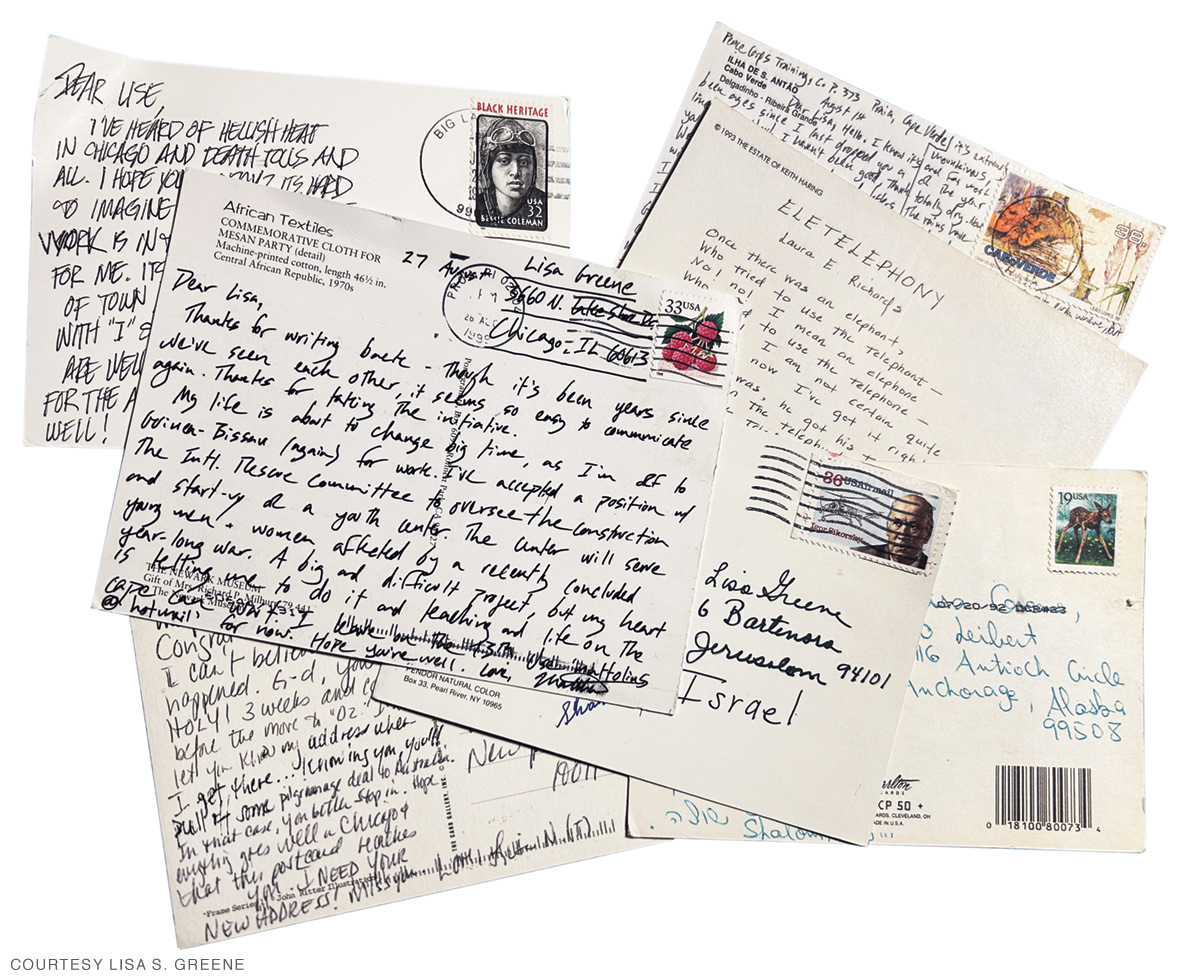

Since college I’ve kept my own collection of received postcards. Recently, I came across buried treasure: a blue Pendaflex folder labeled “correspondence.” It contained a card from Kristi, the hiking guide who kept me going at 12,000 feet in Durango while we backpacked with teenagers in 1996. And one from Andreas, the German PhD student I met in Kyiv during my last summer of rabbinical school. I was teaching in nascent Jewish communities, and on a day I really needed someone to understand me, I stumbled upon Andreas on a street corner. We spoke English, cooked spaghetti and meat sauce, and made enough of a connection to merit an airmail stamp. Other cards bore the wry humor of Ariel, whom I met at her parents’ Passover seder in London during my junior semester abroad, and elegantly penned notes from my Korean soul sister Hye Won, a dorm-mate at Andover when we were 16.

I meditatively read and moved these cards from one side of my desk to the other for a while, and then encountered one that stopped me cold. There was the familiar handwriting I’d not seen in years, on a card Matthew had sent from Cape Verde. “Dear Lisa,” he wrote. “I know it’s been ages since I last dropped you a line. Even though I haven’t been good [about writing], thank you so much for sending cards and letters. Well, I’m about 1/3 of the way finished with Peace Corps training …”

I’d been Matthew’s resident advisor in the Quad when I was a senior. He was a tall, lanky freshman rower from Boston: good-looking, blond, preppy. I was a short Jewish girl with dark curly hair from New Jersey. We shared a certain mix of idealism and cynicism. He’d stand in his doorway in Brooks-Leidy watching his hallmates’ antics with a bemused smile, then sit at the feet of our other friend Lisa, a literature-loving sophomore, and discuss his love of RC Cola, which her father bottled in Chicago. Matthew pledged a fraternity known for WASPy elitism, while I headed home for Rosh Hashanah. We developed an unlikely crush that brought on late-night conversations but no action. I was a rule-following RA, after all.

But our friendship—nay, curiosity—lingered, and after I graduated we remained friends. We visited one another in Boston and Manhattan; he picked me up at the train on his motorbike, and I let him sleep on my couch, even lending him my coveted Levi’s jean jacket. But more than anything, we exchanged letters and cards.

Then we’d lost touch. Several years ago, I found out why. Reading the Gazette, I learned that he had died from ALS. Finding Matt’s cards brought back a friendship that made me laugh and buoyed me to take risks, even as reading his mail aroused regrets. What if I hadn’t been such a rule follower?

The cards in that stack transported me. I saw the faces and heard the voices of the writers—some of whom I still talk to all the time, others I’d have to scour the internet to locate, a few I will never see again. I hold onto these missives in a way that I cannot keep track of a text or email.

And this treasure trove inspires me to keep fresh cards close at hand, in my desk drawer or my purse, each a blank slate awaiting the perfect moment and message.

Stashing postcards is a familiar habit, too. In my parents’ house postcards had a designated drawer in Dad’s desk. A kid could sit there, open the drawer, and be whisked away—to Japan, Jerusalem, Munich, Cincinnati, Illinois. There were ink drawings and faded photographs of double-decker buses and El Al flight attendants, unlabeled art, antiquities, and midcentury hotels. The obverse sides were mostly blank—surplus cards transformed into a historic repository of family travels.

After Dad died suddenly in 2008, Mom reorganized his desk, moving the cards from the top drawer to the bottom. This gave her grandchildren easy access. So my own kids sifted through the cards on visits—even as Mom kept using them too, writing to the grandchildren at summer camp, until Parkinson’s Disease put an end to her inimitable penmanship.

When it came time to empty the desk after Mom died, Jackie told me to choose the cards I wanted before she took the rest. I imagine that she, too, feels the tug of connection to our parents who slid those cards into suitcase pockets while traveling.

So now my parents’ unused postcards are merged chaotically with mine, mixed in with the dozens my kids and I have brought back from our own travels. When I open my card drawer, I can select one that seems right for the recipient and the occasion. I have nearly 70 years to choose from.

I don’t write with an expectation of response, but sometimes I open my mailbox after work and discover a handwritten missive on the back of a glossy image. In recent months, they’ve arrived from New Orleans, California, and London. And my friend Debbie wrote from Manhattan—as she has for years. We met sophomore year in High Rise North and spent the rest of our Penn tenure sneaking snacks from Skolniks Bagels into the Van Pelt stacks.

Debbie credits me with starting her postcard habit 30 years ago. I was heading to Israel as a first-year rabbinic student. She wanted to stay in touch but worried that she wouldn’t write anything because of the pressure to say it all. “Write a postcard,” I told her. “Tell me one thing about your day.” It worked—and still does! The other day I got a fuchsia orchid postcard saying, simply, “Know you always appreciate a handwritten communication.”

And then there was the miraculous postcard from Austin. “Mom,” wrote my college-age daughter Noa. “Today I went to a place that may be one of my favorite places …” The card recounted in meticulous, tiny print the natural rock pool she’d jumped into in Texas, and detailed her Seattle meanderings. I could picture her gleefully plunging in to swim, and exploring bookstores with friends.

But the salutation was what really got me: “Mom.” I’d managed the best part of the postcard-writing ritual: passing it on.

Rabbi Lisa S. Greene W’87 serves North Shore Congregation Israel in Glencoe, Illinois.

Beautiful piece and a beautiful ending. I still try to send the occasional postcard, and I experience such joy to get one in the mail. They’re a slice of memory. Thank you for writing this.