Vantablack

A new collection at the Fisher Fine Arts Library provides a vivid and varied reminder of the “materiality of art” in our digital age.

There’s a black hole in the Fisher Fine Arts Library’s new Materials Collection, and it’s hard to look away. “I feel that if I stare at it too long its gravitational pull will suck me in, and I’ll never be heard from again,” remarked one visitor.

The object in question is 5 inches high, affixed to a piece of crinkled foil inside an unassuming plastic display box. This velvety, super-black coating known as “Vantablack” reflects so little light that when you look at it, the third dimension seems to disappear. It is the darkest material ever created, which is what made it a must-have for the collection, located on the library’s ground floor in space formerly occupied by the old art history slide collection. (The slides haven’t been sucked into that black hole, just digitized and relocated to a storage facility in New Jersey).

The Materials Collection includes nearly 3,000 sample objects ranging from everyday building elements like bricks, wood, and concrete to precious materials of antiquity, such as cochineal (desiccated South American insects once used by the Aztecs to make carmine red dye) and Tyrian Purple (“the most expensive dye, ever”), made from dried snail snot and prized by the ancient Romans for ceremonial robes.

Cochineal

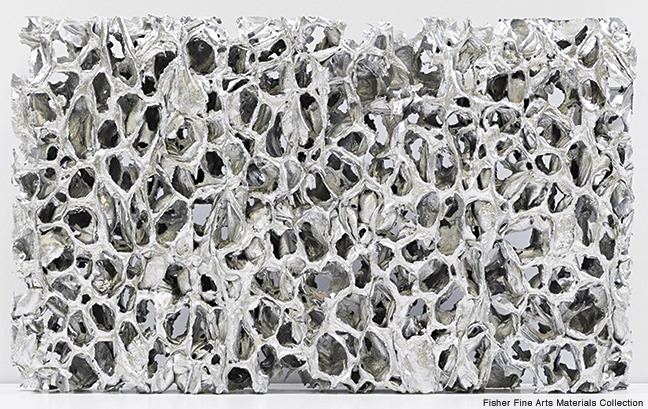

Large cell translucent foam panel

And here are three miniature glass sculptures. The first two—a transparent, Barbie-size pretzel and a honeycomb hexagon—are 3-D printed glass, products of a fusing process that was almost unimaginable a few years ago due to the super-high temperatures previously necessary for working with melted glass. The third is an example of Bioglass, a synthetic biomaterial that bonds chemically with live bone—useful for everything from bone grafts to high-tech toothpaste.

Perched on a houseplant are two examples of fairylike aerogel, an ultralight manufactured material sometimes known as “frozen smoke.” And here’s a 4-D printed, auto-folding, origami-like sculpture from MIT, which has no practical purpose at all—yet—though maybe an enterprising Penn student will come up with one.

There’s more, but the eye is always drawn back to the black hole in the middle of the table.

Vantablack (the name comes from the acronym “Vertically Aligned NanoTube Array”) is a trademarked coating process developed by a British tech firm for use in the aerospace industry. Its light-gobbling property is useful for minimizing stray light in telescopes and has the potential to conceal stealth aircraft. To purchase this sample for the collection, Bennett had to sign an affidavit swearing that she would not be using it for military purposes.

But as a material, Vantablack is as interesting to artists, designers, and philosophers as it is to engineers and physicists. Throughout the art world Vantablack is licensed exclusively, famously—and controversially—to British sculptor Anish Kapoor, whose trademark prohibits other artists to use it. So, of course, the Materials Collection also includes a sample of artist Stuart Semple’s Black 2.0—a deep black acrylic artist pigment that is wryly licensed for use by any artist except Anish Kapoor.

Vantablack and Black 2.0 are emblematic of the collection’s mission to offer support for creative material-based approaches to research and teaching throughout the University curriculum, everything from civil engineering to art history. In this way, the Fisher Fine Arts collection is unique among university materials libraries, which focus exclusively on the needs of design and architecture programs.

Students in “Innovations in Health: Foundations of Design Thinking” last fall were scheduled to take a field trip to the library to learn about the different materials available to them in planning and designing a team project to help solve a healthcare problem or public health need. The course is taught by Marion Leary GNu’13 Gr’14 Gr’23, the School of Nursing’s director of innovation research. A resuscitation science researcher, Leary is working with the STEM library’s innovation intern on a CPR awareness project using electric paint, which she discovered during a visit to the Materials Library while prepping for her class.

This sort of cross-pollination benefits both the creative and the liberal arts facets of the University by opening new ideas and channels of inquiry. PennDesign sculptors drop by the collection to check out new, moldable, high-tech industrial materials or to use one of the library’s handheld 3-D printers. And art history students experience tactile encounters with the elements of artworks that were previously available to them only as flat images on an acetate slide or (nowadays) a glowing screen.

“When I took art history survey courses as an undergraduate, we were sitting in a dark classroom looking at the work on a slide. But in that situation you don’t get to think about the process of art-making itself and, for example, how some materials were prohibitively expensive at the time, or might now be considered toxic,” says Guardiola—who clarifies that they don’t open toxic samples in the presence of students.

In her summer section of Art History 102, an undergraduate survey course of Renaissance through contemporary art, the instructor, Kendra Grimmett, a doctoral candidate in art history, made extensive use of the Materials Library to demonstrate to her students that works of art are more than two-dimensional images on a web page: they are physical objects, created from a variety of natural and highly processed materials.

During their visits, Grimmett’s students touched historical materials traditionally used in Renaissance art, such as lapis lazuli, gold leaf, and Carrara marble. In one session, students created their own egg-tempera paint, mixing the pigments with real eggs, and painted small samples. Later in the semester they examined cutting-edge 21st century technologies and got a firsthand glimpse at copyrighted materials, such as International Klein Blue and Kapoor’s Vantablack.

“Each field trip to the Materials Library promoted the understanding and appreciation of the materiality of art,” says Grimmett. “The questions arise: Where do the materials come from? How much do they cost? How are they processed? And how do materials age after the artist finishes the work?”

Both Grimmett and Leary stress the forward-thinking, collaborative ethos of the Fisher Fine Arts Library staff, who Grimmett says provided detailed information about the available materials in the collection as she prepared for her class visits. “They even acquired materials I asked about, and thoughtfully suggested objects for discussion.”

Gone are the old days when students combed through sleeves of square slides to research or cram for their art history exams. “The physical, analog slide collection was the bread-and-butter of art history pedagogy,” says Bennett. “It was what professors used for exams, for teaching, for in-class discussion. But in the digital age the practice of looking at slides, using slides, and pulling slides for the lectures has gone the way of the dodo.”

The Materials Library brings a new and vigorous purpose to the ground floor of the library, which it shares with The Common Press, Penn’s letterpress printing studio, Bennett notes. “As more and more of the world ‘gets digital,’ and we celebrate the digital humanities and all of these new exciting developments, the fact that we have two spaces devoted to materials—the Common Press and the Materials Library—really underscores the importance of the object itself and of the material within the object,” she says. “And that’s something really hard to intuit through a web page.”

—Karen Rile C’80