A comic superstar, a shy writer, and an unexpected epiphany.

By Marian Sandmaier

A few months ago, I was watching the Golden Globe Awards when 93-year-old Dick Van Dyke emerged from the wings and made his unsteady way to the podium to present an award. At the sight of him, the audience leapt to its feet and cheered, loud and long. And I did the only thing I could do: I jumped up from my chair and clapped, too.

Because he and I have a history.

It stretches back to 1974, when the federal government hired me to write public education materials on the hazards of alcoholism. It was something I knew little about. At the time I was working for a trade magazine on how to conduct successful business meetings. But I wasted scant time worrying about my overall fitness for my new job, because I was too busy freaking out about my first major assignment—to interview a recently recovered alcoholic named Dick Van Dyke.

The idea was for me to persuade the celebrated actor to talk with me in person about his struggles with drinking, write up the interview, and then get it published in Sunday newspapers across the country. At age 26, barely three years out of Penn, I was a tad elated but mostly aghast. I’d never met so much as a local TV weatherman; now I might get a sit-down with the likes of Dick Van Dyke. On the darker side, I was wretchedly shy. I’m not proud of this, but I actually went to my boss to try to weasel out of the assignment. Her lip didn’t exactly curl, but it might have twitched. “Try,” she said.

I trudged back to my office. How would I even get in touch with him? Van Dyke was a notoriously private person. A higher-up at the agency I worked for, the National Clearinghouse for Alcohol Information, told me I was on a fool’s errand, that he’d tried to score an interview multiple times and had gotten nowhere. Naturally, Van Dyke’s phone number was unlisted. All I could get hold of was a box number in Cave Creek, Arizona.

So, I did what I could in 1974: I sat down at my electric typewriter and wrote him a letter. Two pages, single-spaced. I pasted a 10-cent stamp on the envelope and mailed it off.

About two weeks later, I was sitting in my office, drafting some pamphlet on responsible drinking, when my phone rang. I sighed at the interruption. “Hello?” I said, my tone extra brisk.

“Hi,” said a deep, rich voice. “This is Dick Van Dyke.”

“Yeah, and I’m Mary Tyler Moore,” I nearly said, annoyed that someone in my office was pranking me. Luckily, in the next millisecond, I cancelled that response. Instead, I said, “Oh.” Continuing to demonstrate my crack conversational skills, I followed up with, “Thanks for calling.”

Van Dyke got right to the point. He’d be more than happy to do the interview. He could meet me in Los Angeles on such-and-such a date and time. He sounded more reserved than I’d expected, but genuine and down-to-earth. Trying not to hyperventilate, I said, “Tell me where you’ll be, and I’ll meet you there.”

“No, no,” he protested. “Just tell me where you’ll be staying in L.A., and I’ll come to you.” I couldn’t quite process this. Dick Van Dyke was willing to go out of his way for me? I was about to argue, then thought better of it. Mustering my last reserves of composure, I told him the name of the hotel and thanked him again.

When I hung up the phone, I exploded out of my office and sprinted up and down the hall, shrieking, “I JUST TALKED TO DICK VAN DYKE!” Bureaucrats poked their heads out of offices. My boss hugged me.

Ten days later, I flew from DC to Los Angeles and settled into a ridiculously ornate, government-paid suite at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. I went down to the lobby 15 minutes before our appointed interview, prepared for a substantial wait. To my astonishment, Van Dyke was already standing there, hands in pockets, wearing a black turtleneck under a houndstooth sports jacket. He looked for all the world like a regular guy, except that he obviously was the furthest thing from it.

When I introduced myself, he shook my hand and grinned his famous grin. Then he ducked his head a bit and looked off to the side, biting his bottom lip. In the awkward silence that followed, it hit me that this man, this colossal comic superstar, was shy. Since I was hardly a model of social ease myself, the two of us stood there tongue-tied, like two people trapped on a bad blind date. Finally, I said, “Okay, so. Should we go up to my suite?” On the elevator we stood side by side, staring straight ahead.

But as soon as we entered the suite, something shifted. As Van Dyke folded his long body into a chair and lit his first cigarette, his self-consciousness seemed to melt away. Now focused and earnest, he began to talk about the drinking problem that had dogged him for five years in the 1960s and early 1970s and had nearly ruined his life. The story he told me was stunningly at odds with the image he’d cultivated on the hugely successful Dick Van Dyke Show and the first Mary Poppins film—a perpetually sunny, carefree sort of guy. Instead, he drew a portrait of a tense man who never drank on the set but could hardly wait to get home each evening, when he’d promptly open a bottle of high-proof something or other and drink himself into semi-oblivion.

When I asked Van Dyke how he’d finally arrived at his moment of truth, he paused. “I’d always been a very happy, lively kind of a drunk,” he finally said. “Then I began to get angry and aggressive—just a sudden personality change. I frightened myself.”

But he kept on drinking until 1972, when he became so physically depleted and mentally confused that he could barely work. One late night, he was sitting on his living room sofa, soused, and realized he was unable to form a single coherent thought. The next morning, he checked himself into a treatment center. After he told me that, he paused for a moment and then said that during his first year of sobriety, he’d slipped back into drinking before getting help once again. “Which, incidentally, no one knows about,” he told me. “This is the first time I’ve ever talked about it.”

When Van Dyke said that, something in me woke up. I felt insignificant in the best sense. I couldn’t have articulated it then, but I somehow got that this whole experience had nothing to do with me—especially the shyness that had nearly made me reject the opportunity that had made this moment possible. What I witnessed was this man blowing past his own deep reserve and sharing something profoundly personal about himself, something that was brutally stigmatized at the time, but something that might actually change a life. “You out there,” he was saying, “if you’re drinking too much, don’t wait until you’re as wrecked as I was. To hell with what other people think. Save your precious life.”

I felt something shift inside me, something tiny and not quite conscious. Only later did I understand that in that moment, I’d begun to revise one of the big stories of my life, the one that insisted, “I’m shy, so I can’t possibly do that.” Now, a different voice was quietly proposing, “You’re shy, and so what? Go ahead and be awkward. Be uncomfortable. Show up anyway. Because you never know when you might do some good.”

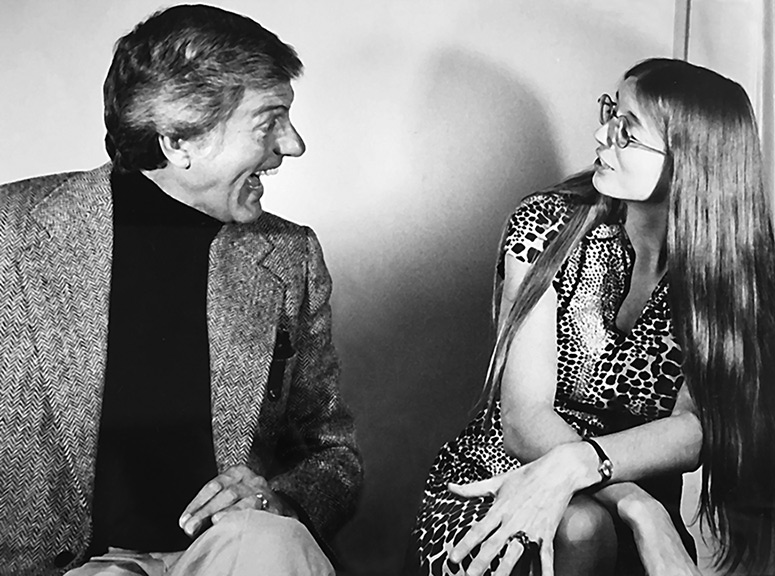

Soon our interview was wrapping up. By this time, a photographer had shown up and was snapping pictures of the actor to accompany the piece. As I switched off the tape recorder and Van Dyke and I began to sink back into mutual self-consciousness, the photo guy spoke up. “Hey, how about I take a couple shots of you two together?”

There was the briefest silence, during which I more or less stopped breathing. Then Van Dyke said, “Happy to.”

“Okay, so turn toward each other and talk,” the photographer instructed, and for a moment Van Dyke and I stared mutely at each other. Then, as flashbulbs popped in our faces, I shrugged at my shyness and started telling him a story, some lame tale about expecting to stay at a bleak Motel 6 for this trip, and then getting booked into the Beverly Wilshire. Crazy, right? And at the same moment, we laughed.

A few weeks after I returned to Washington, the photos came in the mail. To this day, they hang on my office wall. Whenever I look at them, I glow a little: there’s my young self, chatting up a mega-star. Then the glitter factor fades and I take in what’s really going on. Dick Van Dyke and I are looking right at each other. We’re cracking up. Connecting. Two shy people. Even now, as I write this, I’m smiling.

Marian Sandmaier CW’71 is the author of The Invisible Alcoholics and former director of Women’s Programs for the National Clearinghouse for Alcohol Information. She has written for the New York Times Book Review and the Washington Post.

This is such an incredibly beautiful story, and I think only truly shy people will understand it. Thanks for connecting certain dots which most people wouldn’t.

Such a silly thing for me to notice, but he wool weave of DVD’s jacket is actually in the herringbone pattern…not hounds tooth.