The paradoxical power of vulnerability.

By Linda Willing

Several years ago, I spent the month of August working outside of Atlanta. I brought my bicycle with me, hoping to ride after work a few days a week. I was thrilled when I heard there was a rails-to-trails route not far away that would perfectly meet my needs.

But when I told people about my intentions, they warned me. The parking lot was in a bad area, they said. Watch yourself. Don’t linger after dark. Don’t leave anything valuable in your car.

I heeded their warnings. I was careful always to stow everything in the trunk and doublecheck my car door locks. But one day I was in a hurry. It had been a frustrating day at work. I was late arriving at the parking lot for my late-afternoon ride. A minor mechanical problem with my bicycle further delayed my departure. I rushed away from my car, trying to get in some kind of ride before dark.

The ride refreshed me, and by the time I cruised back into the parking lot nearly two hours later, I had let go of all the tension and anxiety I had carried with me when I arrived.

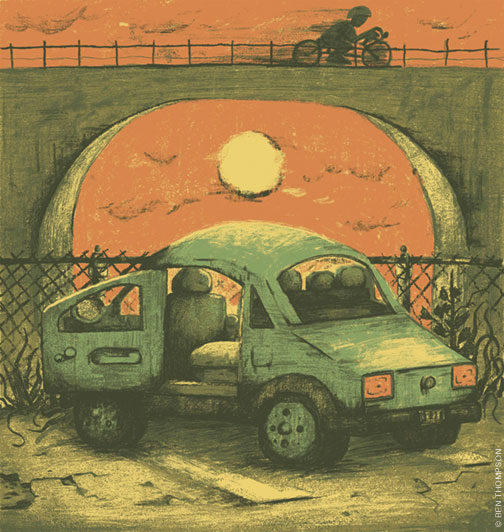

That’s when the cold horror descended on me. As I pedaled up to my car, I saw that one of the back doors was open. My car had been broken into, and as I got closer, a second nauseating wave consumed me. In my impatience to get on the trail, I had neglected to go through the drill of hiding everything away, and had left my purse, my computer, my jewelry from the day, my important papers—everything—in plain sight.

Feeling sick and angry at myself, I hurried to assess the damage. I was so filled with anticipatory regret that I could hardly register the first thing I saw when I peered into the car. It was my computer case, lying on the backseat exactly where I had left it. The surge of relief I felt was tempered by disbelief, and I frantically dove into the front seat. There I discovered my purse, my jewelry, my papers, and everything else I had left behind in the car—untouched and exactly where I had left them.

That’s when it finally dawned on me: I had left the car door open in my haste to get onto the trail. It was an incredibly careless and stupid thing to do—leaving a car door standing open in a public parking lot. But the fact was, nothing happened as a result. No one opportunistically took anything from me, but instead just left my car sitting there, completely vulnerable, until I returned. The battery still even retained enough of a charge to ignite the engine.

I recently revisited this experience while reading Humankind: A Hopeful History, by Rutger Bregman. The book’s basic premise is that people in general are a lot better at their core than we give them credit for. Bregman offers interesting reconsiderations of some of the classic stories that inform modern views of human nature, from Lord of the Flies to Philip Zimbardo’s infamous Stanford prison experiment.

Bregman’s research is compelling, if sometimes selective. Still, I think he’s onto something, and his conclusions echo other testaments to cooperation and solidarity among strangers, such as Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell, which explores communities of mutual support that develop with remarkable frequency and depth in the wake of disasters.We hear such stories all the time: the nurse who flew from Alaska to help earthquake survivors in Haiti; the person who donated a kidney to a neighbor; the volunteer flotilla that arrived to rescue people after Hurricane Katrina.

I’m not really an optimist at heart, but these stories resonate for me. I’ve experienced the compassion of strangers in my travels and my work as a firefighter. As an undergraduate at Penn in the 1970s, I spent many days walking the streets of the city by myself. It was as valuable a part of my education as any class I took. I explored churches and galleries, I had conversations with random people in parks, I lingered over coffee in tiny cafes on less-traveled side streets. In four years, I never had a bad experience.

When I tell people the story about leaving my car open in the parking lot that day, they tend to react in the same way. “Well, of course no one would mess with your car, with the door standing wide open like that,” they say. “Nobody would approach a car under those conditions. They would assume it was a trap.” They’re probably right. But this response also recognizes that there may be some power in allowing ourselves to be vulnerable. If standing wide open can protect us, why don’t we do it more often?

Bregman offers this advice: “Be courageous. Be true to your nature and offer your trust. Do good in broad daylight and don’t be ashamed of your generosity. You may be dismissed as gullible and naïve at first. But remember, what’s naïve today may be common sense tomorrow.”

My own experience in the world leads me to a somewhat different but possibly complementary conclusion: don’t be stupid, but don’t be afraid either.

On Christmas Day during my junior year at Penn, I took the train into the city, intending to meet up with friends the next morning for a winter break trip to Florida. A friend told me I could stay overnight at her empty house at 43rd and Pine Streets. Thirtieth Street Station was festive and busy with people returning from holiday gatherings. I got on the trolley but decided to get off at 37th Street, thinking I could pick up a can of soup for dinner from the mini-mart nearby.

When I got off at that stop, there was no remaining holiday cheer, just a sense of foreboding. The station was deserted and as I emerged from underground, the bad feeling intensified. The campus on Christmas night was a ghost town: dark, abandoned, and threatening.

Now I was faced with walking the eight blocks to my destination for the night. I was dressed like a target—a bright green winter jacket, a pink wool hat, and a flowered canvas suitcase banging against my leg. I was nervous, but I figured I would just keep my head down, keep moving, and everything would be fine.

I had barely made it across 38th Street when someone emerged from the shadows—a large man who came right up next to me and asked if I had change for a dollar. I’ll admit it, I was scared. I dug into my pocket and pulled out a handful of coins. “Here,” I told him, trying to move away, “Take it.”

He lingered next to me. “I don’t feel right just taking your money,” he said. “Isn’t there something I can do for you?”

I looked around. It was dark. I was alone and if this man wished me harm, he could do me harm wherever he wanted. “Yes,” I said. “If you want, you can walk with me to 43rd and Pine.”

And he did.

Linda Willing C’76 is a former urban firefighter, National Park Service backcountry ranger, and the author of On the Line: Women Firefighters Tell Their Stories.

A point of light in a news cycle that focuses on fear. Thanks Linda.

Thanks, Linda. That is beautiful, and helps us allow ourselves to change our expectations. I am an optimist, and continue to try to shed light, support, and love everywhere I am. Best, Tom

excellent article, thanks for sharing