An anti-death penalty lawyer and author exposes some of the ills of capital punishment.

Convinced that the government was conspiring to read his mind, Andre Thomas ripped out his left eye and ate it while locked up in a Texas prison cell in 2008. This happened about four years after he gouged out his right eye, following his arrest for the brutal killings of his estranged wife and two children.

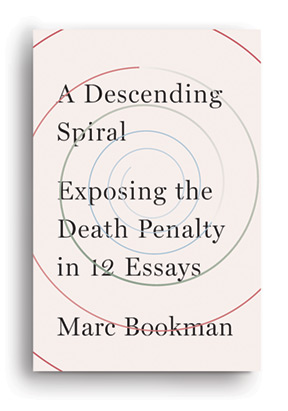

Yet despite exhibiting an extreme form of psychosis and experiencing hallucinations since the age of 10, Thomas’s insanity plea was rejected after the first eyeball incident, and to this day “Texas continues to pursue Andre’s execution,” author and anti-death penalty crusader Marc Bookman C’78 writes in his 2021 book, A Descending Spiral: Exposing the Death Penalty in 12 Essays (The New Press). “No state authority figure has expressed hesitation about ending the life of a man who intentionally blinded himself, nor has there been any move by the district attorney to reconsider Andre’s mental state at the time of the killings.”

Sitting outside of Houston Hall on a drizzly September afternoon, Bookman becomes even more animated talking about Thomas, whose patterns of schizophrenia, he argues in his book’s second chapter, “How Crazy Is Too Crazy to Be Executed?”, were profound and longstanding. But even though the Supreme Court ruled in 2002 that intellectually disabled people are exempt from capital punishment, the courts have not shielded those with severe mental illness from the death penalty.

“It’s remarkable, isn’t it? It gives you a sense of just how driven the government, the state, can be to execute someone,” says Bookman, a former public defender who now runs the Atlantic Center for Capital Representation, a nonprofit death penalty resource center serving Pennsylvania and Delaware. “To execute a guy that mentally ill is beyond the pale.”

An even “more insidious aspect” of Thomas’s trial, Bookman writes elsewhere, is the fact that three jurors had noted on their jury questionnaires that they opposed interracial marriage and yet still landed on the jury, where they rejected the insanity defense and voted to give Thomas the death penalty rather than life in prison. (Thomas is Black, and his wife that he killed was white.)

Other essays explore a negligent prosecutor, a racist and anti-Semitic judge, and a drunk defense attorney who failed to reveal his client, Robert Wayne Holsey, was an “extremely low-functioning man who had been raised in poverty and terrorized physically and mentally by a vicious, violent, and psychotic mother,” Bookman writes. Holsey was executed in Georgia in 2014 after the Supreme Court denied another attorney’s appeals about Holsey’s intellectual disability and alcoholic trial lawyer who later landed in prison himself.

“I think it’s important for the public to expand their understanding of injustice,” Bookman says. “It’s not just an innocent person who’s in prison. When a Jewish defendant is presided over by an anti-Semitic judge, or when prosecutors are hiding evidence, or when attorneys are drunk or not paying attention, that’s a real injustice. And when you’re talking about the death penalty, it’s an injustice that can’t be tolerated.”

Bookman says he felt “uniquely qualified” to write these essays, some of which he had already published in various online outlets before updating them for the book. At Penn, he waffled between becoming a writer or a lawyer, ultimately deciding on the latter because he figured he could still write. After attending law school at the University of North Carolina (during which he took a three-day train trip to Utah to watch the Penn men’s basketball team play in the 1979 Final Four), he considered becoming a prosecutor, “because prosecutors have all the power, and if you want to do social justice, it’s nice to have power.” But he was persuaded by his mentors to become a public defender, “which was obviously the right choice at the time.”

Starting in 1983 as a Philadelphia public defender, Bookman quickly got a sense of how the system grinds through poor people. “It’s your job,” he says, “to stop the grinder as best you can. It’s not about systematic change; it’s stopping injustice in your small corner of the world.” Calling every day a “constant fight,” he derived motivation from the Samuel Beckett quote: “I can’t go on; I’ll go on.”

Bookman spent 27 years at the Defenders Association of Philadelphia, the last 17 in the homicide unit, before cofounding the Atlantic Center for Capital Representation, a hands-on litigation organization based in Center City Philadelphia that provides free assistance to lawyers on capital cases. The nonprofit’s goal, Bookman says, is to “reduce death sentences to such an extent the policy doesn’t make sense anymore.” Its slogan, which Bookman says came to him in his sleep, is: “Trying to put ourselves out of business since 2010.”

Bookman is cautiously optimistic that day might come. His book ends on a hopeful note—executions and death sentences in the US have dropped more than 75 percent from their highs of two decades ago. “And there is no evidence to suggest these trends will reverse themselves,” he writes.

But there are still battles to be fought, even in his home state of Pennsylvania, which hasn’t had an involuntary execution (on someone who gave up their appeals) in almost 60 years and is currently governed by an executive moratorium on the death penalty. (Two other states have imposed similar moratoria and 23 states have eliminated the death penalty entirely.) One of the most “outrageous” essays in his book tells the story of Terry Williams, whose execution the former Philadelphia district attorney tried to secure even though Williams, at 18, was convicted of murdering two older men who had sexually abused him as a minor. Larry Krasner, Philadelphia’s current district attorney—who Bookman believes is “doing very good work” after being elected as a criminal justice reformer vowing never to seek the death penalty—has since moved Williams from death row to the general prison population.

“I think slowly but surely we’re persuading the population this is not popular anymore,” Bookman says. “And it’s up to the population to persuade their elected officials that they don’t want this.” What’s changed the most since support for the death penalty peaked in the mid-1990s—public opinion polls have showed its popularity declining ever since—is “a really important recognition of systemic racism,” Bookman adds. “And as reform prosecutors like Larry Krasner get elected, over the course of time we’re going to see real change, decarceration, and much more social justice. And getting rid of the death penalty is fundamental to that movement.”

While his book and his work focus primarily on people who have been wrongfully accused or wronged in other ways during their trials, the book’s title and epigraph illuminate his moral stance on the death penalty even for those who committed the most heinous crimes in open-and-shut cases. He quotes Martin Luther King Jr.—“The ultimate weakness of violence is that it is a descending spiral, begetting the thing it seeks to destroy”—and later, speaking passionately about being “on the right side of history,” uses The Lion King as an analogy. Near the end of the Disney film, which he once used as a lesson for his children when they were growing up, the protagonist Simba has the chance to kill his father’s killer, Scar, who asks Simba if he intends to do just that. “No, Scar, I’m not like you,” Simba responds, banishing him from the kingdom rather than executing him.

“Simba’s words are the right words,” Bookman says. “Somewhere between the age of 6 and adulthood, we lose sight of the fact that it’s not right to act like my clients acted on their worst day.” —DZ