Solitude and Sanctuary: John Brown’s 40 Days and Nights

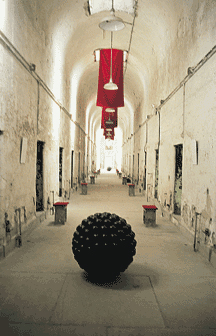

In the dank, deserted cells of Eastern State Penitentiary, the toilets are now clogged with fallen plaster and the sun squeezes through the skylights to reveal leprous walls—designed almost two centuries ago to hold criminals in penitent solitude.

But in the hands of Dr. Terry Adkins, associate professor of fine arts, one of the cellblocks has taken on a majestic air not typically associated with prisons. Red velvet banners hang from the vaulted ceiling of the cellblock. The spartan benches that inmates once sat upon are now covered with the same rich fabric to look like something one would kneel on inside a church. “I tried to make it into a cathedral,” the sculptor says of his installation, entitled Sanctuary. “My intention was to give [the space] this majestic, sacred kind of feeling.” Adkins was one of several artists who won a competition to set up an installation inside Eastern State. Closed as a prison in 1971, the facility now operates as an historic landmark.

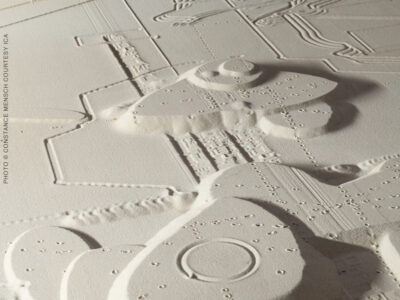

Sanctuary meditates on the abolitionist John Brown and his time in a Virginia prison—“40 days and 40 nights, like Jesus in the desert.” While imprisoned Brown wrote many letters that showed his “single-mindedness and purpose,” Adkins explains. “He used the dire circumstances of this incarceration and turned it into a monastic experience.” Adkins altered 40 cells—one for each night—to represent various aspects of Brown’s life, focusing on him as “a shepherd, a prophet, a soldier, and a martyr.”

African spears surround a rusty prison bed frame inside one cell. “They’re modeled after some pikes John Brown had fabricated up north. He was going to arm fugitive slaves with these.” Columns of black and white feathers stand at attention on a bridge made of rope in another cell. “It has to do with the bridge at Harper’s Ferry” in Virginia, where Brown led his famous 1859 raid. The feathers symbolize an eagle’s keen eyesight. “It leaves no doubt about John Brown’s clarity of vision, his purpose, and the consequences of his actions.”

Adkins says he has chosen Brown repeatedly as a subject, because “he is a singular, enigmatic figure in American history that Americans would somehow like to disavow. In some circles he’s considered to be a traitor, a madman, and a criminal, when, in fact, all these depictions of him are quite generalized and unfair. For black Americans, John Brown is an entirely different person. We see him as more of a hero and a martyr.” Adkins has created John Brown exhibitions, or “recitals,” as he calls them, in several locations, including the University of Florida and the University of Akron, adding new sculptures while reusing and reworking others.

While Eastern State is an exciting venue for a sculptor to work within, there are certain drawbacks to displaying one’s art in a 170-year-old prison. For one thing, you can’t nail anything into the crumbling walls. “The piece with the eagle feathers is tied to the radiators.” Another problem is the persistent dampness of the place. Positioned in the long hall are two giant spheres covered by smaller black balls, which represent “the souls of black folks.” Adkins inquires if they were intact during a recent visit to the prison. “The balls keep falling off because of the humidity.” —S.F.