Photo by Chris Crisman

Like every kid in Titusville, a small town in the northwest corner of Pennsylvania, Chris Crisman C’03 spent a week of sixth grade at hunting camp, learning how to shoot a rifle. All was well when his parents dropped him off at the beginning of camp, but something was different by the time they picked him up. He vividly remembers being hit with a sense of foreboding as he got in the car.

“They told me things were going to change a little bit,” he says. “People were going to start getting laid off.”

Crisman’s father had worked as an hourly shift-worker at Cytemps Specialty Steel for 21 years, alongside his brother, most of his friends, and his own father. When parent company Cyclops Industries unloaded its steel entities in the early 1990s, the tenor of Titusville changed. Reps from the steelworkers’ union—Crisman’s dad is a vice president—battled with their corporate counterparts for long hours behind closed doors. Titusvillians kept their radios tuned to the local news for the latest updates on the arbitrations. Everything was at stake—their livelihood, their health. Almost all of the steelworkers had sustained multiple injuries over the years. The list for Crisman’s father begins with two disintegrated discs in his back, three heart surgeries, and a replaced hip. “And that’s just the physical stuff,” Crisman adds.

His dad was one of the lucky ones—he’d worked just long enough for his pension and benefits to kick in.

“It was a strange time,” Crisman remembers. As a teenager at Titusville High, he was aware of a general mood shift and of specific changes, like his dad going to work at a Salvation Army two days a week and his mom’s dog-grooming business suddenly becoming the family’s major source of income. But the big picture—the realization that he’d witnessed the end of an era—didn’t begin to emerge until he left his hometown and matriculated at Penn. As an undergrad, the pull of Titusville grew stronger and stronger until it even made its way into his coursework.

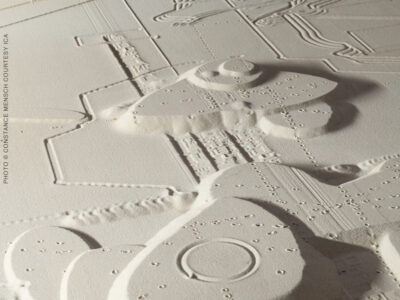

In 2002, Crisman, a double major in environmental studies and photography, received a Nassau Fund grant to document western Pennsylvania’s vanishing steel industry. He made the 12-hour round trip home several times that year to produce a series of photographs of Titusville’s hulking, abandoned steel mills.

After graduation Crisman stayed in Philadelphia and wedged his foot in the door of the commercial-photography business with gigs as an assistant. Whenever he returned home to Titusville, he’d read obituaries in the local paper of former steelworkers. They were dying a lot younger than they should’ve been.

“I had it in the back of my mind that I wanted to do portraits of these guys while they were still alive,” he says. “I realized that documenting the buildings wasn’t as important, that the American steelworker is iconic, and that soon they’re not going to exist anymore.” Crisman’s father asked around and made some appointments. Then he went along with Chris and talked with the guys while his son set up lights and scouted for the right shot.

Photo by Chris Crisman

Photo by Chris Crisman

Photo by Chris Crisman

The resulting series, “Titusville Steelworkers,” was one of 140 projects out of 8,461 entries to win Communication Artsmagazine’s 47th annual photography competition. The publication featured five portraits in their August issue. And based on the series, the Canadian Magenta Foundation named Crisman one of 20 emerging U.S. photographers in 2006 and included his work in a book that came out in November. Some of the shots, blown up to 40 x 60 inches, were exhibited at F.U.E.L. gallery in Philadelphia’s Old City in August. The effect when they’re enlarged is mesmerizing.

Photo by Chris Crisman

Some of the compositions pay homage to the longstanding tradition in portraiture of letting props invoke a sitter’s character. Lou Locke, in uniform and holding an American flag, stands in a doorway surrounded by framed pictures of his family, Jesus, a souvenir postcard from Chincoteague, and an illustration of two bucks locking antlers. Lester Warner sits in a beige armchair; on the wall behind him hang a buck mount, a collection of wall clocks, and a pair of flowery drapes. His glass-front gun cabinet is set up in the corner.

Crisman fits the work in between his paying jobs: taking photos for magazines and advertising, commercial, and corporate clients. He likes the balance of commercial work with self-funded fine-art projects.

“There’s a different level of intimacy with the steelworkers,” Crisman says. “These guys are really comfortable in their skin.” Some of the steelworkers think the photo shoots are exciting; for others, it’s quite the opposite. Lester Warner was the most hesitant—he feared someone might filch his guns.

Each time Crisman steals home to make more pictures, he reads more obits and feels a sense of urgency all over again. “But none of the guys I’ve shot have passed,” he says. He thinks for a second. “Yeah, none of the guys have passed yet. Maybe it’s a good omen for them.”

—Caroline Tiger C’96