Sex, Suicide, and Snapchat: Adolescent Health in the Digital Age

Ask parents about their kids’ use of social media and texting, and chances are they will voice dismay about the amount of time spent online, the content encountered there, the danger kids run of becoming targets of bullies or other predators, sexting, and the inevitable loss of interpersonal skills. Those predictions, while incredibly common, are not coming to fruition, says Dan Romer, research director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC). Parents’ concerns are not only over amplified but, in most cases, flat out wrong.

“A lot of assumptions are not holding up under examination,” Romer says. “So far, the evidence is either not clear about negative impacts, or it’s going the other way and showing that kids who are well connected on social media are not becoming social isolates or necessarily engaging in risky behavior.”

In fact, a new and wide-ranging assessment of research shows that social media and texting appear to be enhancing the lives of most adolescents. No matter the platform—be it social networking, mobile apps, internet searches, or gaming—the results were the same.

“Many are better off because of those technologies,” Romer says. “They are in touch with friends, including those outside their immediate geographical areas. We think being connected online is a good thing. If there are bad things about social media and texting, they are balanced by the good things.”

Romer and his colleagues reported their conclusions in a special issue of the journal Media and Communication titled “Adolescents in the Digital Age: Effects on Health and Development.” Released in June and edited by Romer, the issue compiled research conducted by a team of experts from a variety of disciplines and academic institutions, including physicians, public health professionals, and communications experts from the University of Oregon, Northwestern, University of Sydney, Ursinus, Penn’s School of Nursing and the Perelman School of Medicine, as well as the APPC, which sees itself as a natural home for such cross-disciplinary collaboration.

Romer and his colleagues examined some of the greatest hits of teenage taboos: sex, alcohol, drugs, and cigarettes. Some authors drew together evidence from a variety of studies previously conducted by the Pew Research Center, Common Sense Media, and other national organizations, while others conducted original research via online surveys.

They found that, contrary to popular belief, social media are not having a direct impact on risky adolescent behaviors. Romer and his colleagues note that in broad terms, this is not all that surprising; after all, the results of those risky behaviors—including car accidents, unintended teen pregnancies, transmission of STDs and HIV, and teen smoking—are at all-time lows, despite the prevalence of social media.

But problem areas remain, including bullying, gun violence, and suicide, though the research is mixed on the impact of social media on them. For example, Romer referred to an old academic finding that teens who experience the suicide of friends or family members are more likely to attempt it themselves. But Romer cited more recent research indicating that kids who hear about suicides on Facebook are less likely to attempt it themselves, possibly because they see messages of love and support posted for the person who died and his family. However, adolescents who go into suicide-themed chat rooms do have a high rate of attempts, even if they are looking for help. Romer, who says that more research needs to be done in that area, admits to frustration in finding clear ways to counteract negative messaging through social media, or any kind of media. In fact, one of the special issue’s big takeaways is that the current digital media landscape has made it increasingly hard to deliver any kind of positive public-health messages to adolescents, since teenagers live in social media worlds that are difficult for adults to penetrate.

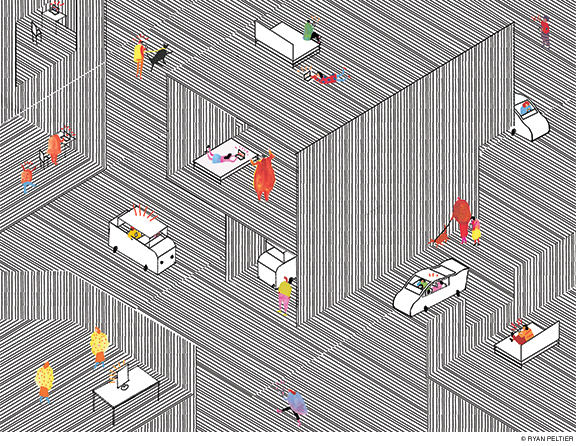

“Digital neighborhood” is the term used by Robin Stevens Gr’09, director of the School of Nursing’s Health Equity & Media Lab, to describe the personalized social-media realms organized around the music, sports, books, and movies teens follow online.

Identifying and targeting digital neighborhoods is critical to understanding the behaviors of adolescents from various backgrounds. Stevens co-authored a paper that continues her research into the ways social media influences the sex lives of African-American and Latino teenagers, particularly those who live in poor or lower-middle-class areas.

“Most research is done on white, suburban adolescents who live in good neighborhoods, so we have to be careful about blanket statements if we don’t have good data about black and Latino groups,” Stevens says. She adds that even ethnicity is a limited guide to where a given adolescent will spend time in the virtual realm. “Take two young people of the same age, race, and geography. One is gay and one is straight. They will have very different digital neighborhoods.”

Regardless of their digital neighborhood, adolescents commonly use the internet to learn about health-related issues like birth control. Unfortunately, Googling anything related to sex usually leads to a cornucopia of pornography, Stevens says. She is researching methods of using social media to provide teenagers with correct and positive information about everything from relationship advice to reviews of local, teen-friendly clinics and doctors, and the positives and negatives of various birth control methods.

A key to transmitting information about sex—or drugs, drunk driving, or any other risky behavior—is accessing the digital neighborhoods in which the adolescents live. Furthermore, Stevens says, lecturing kids won’t work and never has. What’s needed are authentic messages delivered by credible messengers, people Stevens calls “super peers.”

Enlisting them in public health campaigns is a must. “Any positive message needs to come from within,” explains Amy Bleakley, a senior research scientist at the Annenberg School who co-authored two papers in the special issue. “You need to nurture these campaigns, plant little seeds and gain credibility in groups. It has to be a genuine attempt on the part of the people involved to incorporate the dynamics of youth.”

Among risky behaviors identified by the special issue’s authors is internet use itself. As Romer explains, there’s no clear academic or clinical definition of internet addiction because it is hard to quantify. So, in the Annenberg Media Environment Survey, Romer, Bleakley, and their co-authors identified 1,833 US kids aged 12-17 whose internet use displayed addictive tendencies, including staying online longer than they intend to, frequently thinking about going online when they aren’t, and having online behavior negatively impact offline lives. Of that group, 899 parents also answered survey questions.

Bleakley laughs as she describes how seldom parents accurately judged their kids’ online usage. “They have no clue,” she says, “and while that is not entirely surprising, it does confirm how out of touch parents are with kids’ problematic internet use.”

Parents’ efforts at restricting their kids’ online behavior have been largely ineffective. Romer and his colleagues grouped those efforts into two approaches: “mediation” and “monitoring.” Mediation includes conversations about social media, rules about its usage, and co-watching suspicious content. According to Romer, those methods simply don’t work. In fact, they backfire.

“Mediation that included checking their child’s email/online accounts or installing tracking software was actually related to participation in more online risky activities,” the authors wrote. The reasons are timeless. “They don’t want to be told what not to do, and view those messages as authoritarian,” Romer explains. “It gives them something to rebel against, so they do.”

Much more effective is monitoring social-media behavior, which includes calm conversations between parents and adolescents. Bleakley admits that’s a big ask. “Parents think they are acting in the best interest of their kids and they want to take action,” she says. “But the key is to focus on the mindset of an adolescent, not the world of social media.”

To that end, Romer just finished work on a new version of Treating and Preventing Adolescent Mental Health Disorders , first published in 2005. Scheduled for publication in 2017, the book’s chapters on depression, eating disorders, drug use, and suicide are updated to reflect the influence of social media, and there is new material on subjects like internet addiction and online gambling. But based on the journal issue he edited, one takeaway is that while the digital realm contains hazards for adolescents, parents would do best to focus most of their attention on what’s happening in the real one.