A new book untangles the legal arguments and unintended consequences of Church v. State.

By Dennis Drabelle

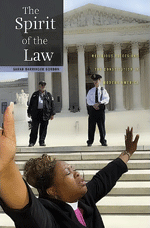

THE SPIRIT OF THE LAW

Religious Voices and the Constitution in Modern America

By Sarah Barringer Gordon, faculty

Harvard/Belknap, 2010. $29.95.

Sarah Barringer Gordon has written a lucid and fruitful study of what might be called “demotic law”: the way in which non-lawyers give new meaning to the US Constitution by suing to vindicate rights not spelled out in the text but seemingly embraced by its spirit. The field in which she has chosen to observe this phenomenon is religion, which calls for balancing the free-exercise clause of the First Amendment with the requirement that church and state be kept separate. Cases arising under the First Amendment can be dauntingly complex. But Gordon, the Arlin M. Adams Professor of Constitutional Law and professor of history at Penn, explains them clearly and without lapsing into jargon.

She begins with the Jehovah’s Witnesses—and Katherine Graham’s wedding. In the summer of 1940, the future publisher of The Washington Post had to wait as the ceremony was delayed to accommodate a debate that had broken out at the pre-wedding lunch. One of the guests, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, was defending his majority opinion in the recently decided case of Minersville School District v. Gobitis, in which the Court ruled that the Constitution did not bar a school from requiring students to salute the flag, even though their faith adjured them not to worship false idols. One debater got so exercised that he wept, and Frankfurter defended himself by saying he’d never claimed to be a liberal.

By today’s lights, Frankfurter seems in the wrong. To be fair, he hadn’t been wholly unsympathetic, suggesting that the Jehovah’s Witnesses turn to the state legislature (Pennsylvania’s) for an exemption. Only one member of the Court, Harlan Fiske Stone, had dissented, but not long afterward he was elevated to chief justice. Three years after Gobitis, the Court reversed itself in another flag case, West Virginia v. Barnette, holding that, under the First Amendment, freedom of conscience trumped the state’s interest in fostering loyalty among its citizens. This time Frankfurter found himself in the minority, warning that the decision would unloose a flood of litigation and force the Court to decide whether a given body of beliefs amounted to a religion or not.

Frankfurter’s “prescience was remarkable,” Gordon notes. “Visceral satisfaction with the result in Barnette has been followed at the Supreme Court by decades of tortured reasoning and unpopular rulings.” (One maligned decision, at least when first handed down, was Engel v. Vitale, which held that the state of New York could not conduct an official prayer in its public schools.)

The Jehovah’s Witnesses look principled and heroic—until you examine their behavior more closely. According to Gordon, the church used secret courts to “disfellow” members for such infractions as drunkenness. “Jehovah’s Witnesses claimed tolerance for their intolerance,” she concludes. The moral is that case-by-case translation of the law’s spirit into reality is a messy process that can lead to unpredictable results.

Another example of how hard it is to control the law can be seen in the career of Beverly LaHaye, who in 1979 founded Concerned Women of America (CWA) to shore up the patriarchal family. The new group sought to expand the freedom of conscience embedded in the First Amendment by such enforcers as the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Accordingly, CWA backed lawsuits pressing the argument that secular humanism is a religion in disguise, and that it was taking over the public schools. In one case, a mother argued that it was unconstitutional to force her kids to use a reader containing material she considered at odds with her Christian beliefs. A lower court sided with the plaintiffs: as Gordon characterizes the result, the state (Tennessee) was ordered to let the kids “opt out of the reading program, study at home, and … take standardized tests for reading skills.”

What at first appeared to be a dramatic victory, however, did not hold up. An appellate court did what lawyers do best: draw distinctions. Reading a textbook was not the same as pledging allegiance to the flag, the court said. The kids weren’t being required to espouse what they read, simply to master it. Since that decision (Mozert v. Hawkins County Public Schools), Gordon notes, “arguments that secularism in public schools violates the free exercise rights of students and their parents have been rejected virtually across the board.”

Not only did CWA lose a big case; in later years the unabashed religiosity they brought to lawsuits involving marriage and the family seemed to backfire on them, as gay men and lesbians argued that limiting marriage to opposite-sex partners illegitimately enshrined religious beliefs in civil law. Ironically, LaHaye had founded CWA partly as a riposte to the National Organization of Women, which she perceived as a hotbed of leftist lesbians.

Gordon covers numerous other topics, always keeping an eye out for the human detail that adds psychological interest. In the end, she cites with a hint of approval a sentiment expressed by former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor: that on the whole, this grassroots movement has led to an increase in religious tolerance. At any rate, Spirit of the Law is a fascinating and valuable account of ordinary people trying to make the Constitution live up to its inspiring words—and sometimes getting more than they bargained for.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is a contributing editor of The Washington Post Book World.