When the Christian Association relocated this winter, it took the mural Sam Maitin created 15 years ago along—and commissioned him to do a new one, too.

By Jane Biberman

As a Jew, I love the CA because it has always frowned on quotas and protected minorities,” says Sam Maitin FA’51. ‘‘I hung out there as a student and as a teacher because I was attracted to its ecumenicalism and its agenda of social activism. They have always been, and still are, in the forefront of the kind of community action that I think is important.”

Maitin has done a lot more than just hang out at the Christian Association. The artist, himself a social activist who has contributed much of his time and work to causes like the anti-nuclear movement and protesting the Vietnam War, created a mural for its Chapel of Reconciliation that provided solace and inspiration to visitors for 15 years. This past winter, the mural was moved to the association’s new campus home. Maitin was the guest of honor at a dinner and ceremony marking the organization’s move, and he is now in the midst of developing another mural for the new location.

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants who owned a grocery store in North Philadelphia, Maitin enrolled at Penn in 1945, when he was just 16. He “couldn’t believe” Penn accepted him, he says, adding that there were quotas for Jews at the time and “I was sure I wouldn’t make the final cut.” Maitin was also attending what is now the Philadelphia College of Art on a scholarship he won in high school; he took Penn courses at night, in art history as well as other subjects, and graduated with a bachelor of fine arts in 1951.

Maitin worked as a teacher, printmaker, and graphic designer, eventually establishing himself as an international artist of the first rank. Today, at 72, his silkscreen prints, paintings, and sculptures can be found at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, and the Tate Gallery in London. But Maitin is best known for his public art; his signature murals and three-dimensional constructs—abstract, joyful, and colorful—that enhance communal spaces around the globe.

On the Penn campus, Maitin’s polychrome dimensional mural, “Celebration,” enlivens the lobby of the Annenberg School for Communication, where he taught from 1966-1970. Over the years, he has contributed banners and prints to the Wharton School, the Dental School, and the School of Arts and Sciences. But perhaps he is most of proud of the sectional mural he made for the CA.

In 1983, Rev. Ralph Moore, the association’s former executive director, commissioned Maitin to paint an 18- x 8-foot mural. “I went to study the space and the light,” says Maitin. “There was a Penn student standing there on one foot, meditating. I realized that this room, which Ralph called the Chapel of Reconciliation, was for everybody.” It took Maitin two years and 100 sketches to complete the acrylic mural that incorporates the words of the late Penn professor and writer Hiram Haydn: “As they flew low over me, there was no sound but the beating of their great wings, like blows of peace from God.”

Maitin constructed a trolley in his studio so that he could paint the long mural on the floor. His wife, Lilyan, pushed it back and forth, following her husband’s directions: to the left, to the right. “I couldn’t have painted it standing up because I wanted to use a wash effect, with no sharp edges,” explains the artist, adding that he believes “the final effect is appropriate because it remains quiet and non-intrusive.”

It is based, he says, on a theme that is barely suggested: the elements of earth, fire, water, and sky. And the sky is enhanced by winged shapes or creatures that are mentioned in Isaiah. On the lower right-hand side, in pencil, the artist wrote “Kadosh, Kadosh, Kadosh” (“Holy, Holy, Holy”). Moore, who now lives in Rockland, Maine, but remains a close friend of Maitin’s, remembers: “Although the mural dominated the space, it seemed to welcome people of all faiths to come and sit and ponder. Buddhists, Christians, and Jews all came to meditate in front of it.”

Over time, the CA’s home at 3601 Locust Walk had become too large and costly to maintain, and the University bought the building in 1999. The association’s new quarters are in the former parsonage of Tabernacle United Church at 118 S. 37th Street. (This is the third home for the CA, which was established in 1891 as a campus outreach of the YMCA; it was originally housed in Houston Hall until 1928, when it moved to Locust Walk.)

The mural was recently moved to the Great Room of the new building. Because the space is smaller, the mural doubles as a wall and becomes the focal point of the ground-floor room, which is used for meetings and social gatherings. The Chapel of Reconciliation is now on the third floor. At the moment, its sloping walls are bare, but the CA’s current executive director, Rev. Dr. Beverly Dale, commissioned Maitin to create another mural conducive to reflection and contemplation.

“Sam has a long history with the Christian Association,” says Dale. “His tradition of activism coincides with our understanding of social justice. We approach it from different religions, but we are on the same page. Sam understands the importance of interfaith aspects.”

While its location has changed, the organization’s mission remains the same. “It is a place where minds open and faith works,” says Dale, adding that it “promotes tolerance, dialogue, and the critique of culture and Christian tradition.” In recent times, it has supported the domestic-partnership laws for gays and lesbians and offered counseling and emotional support for women concerned about issues of reproductive planning. “We are also concerned with the persecution of Muslims in this country that grew out of Middle East conflicts,” says Dale. “We have always had one foot in the community and one foot on campus.”

A coffee house is planned for the new space, where poets, artists, and musicians concerned with social justice may perform. A reading program will pair the elderly residents of a retirement home with third- and fourth-graders; and Penn students will be given the opportunity to work for Habitat for Humanity, and help people living with HIV/AIDs.

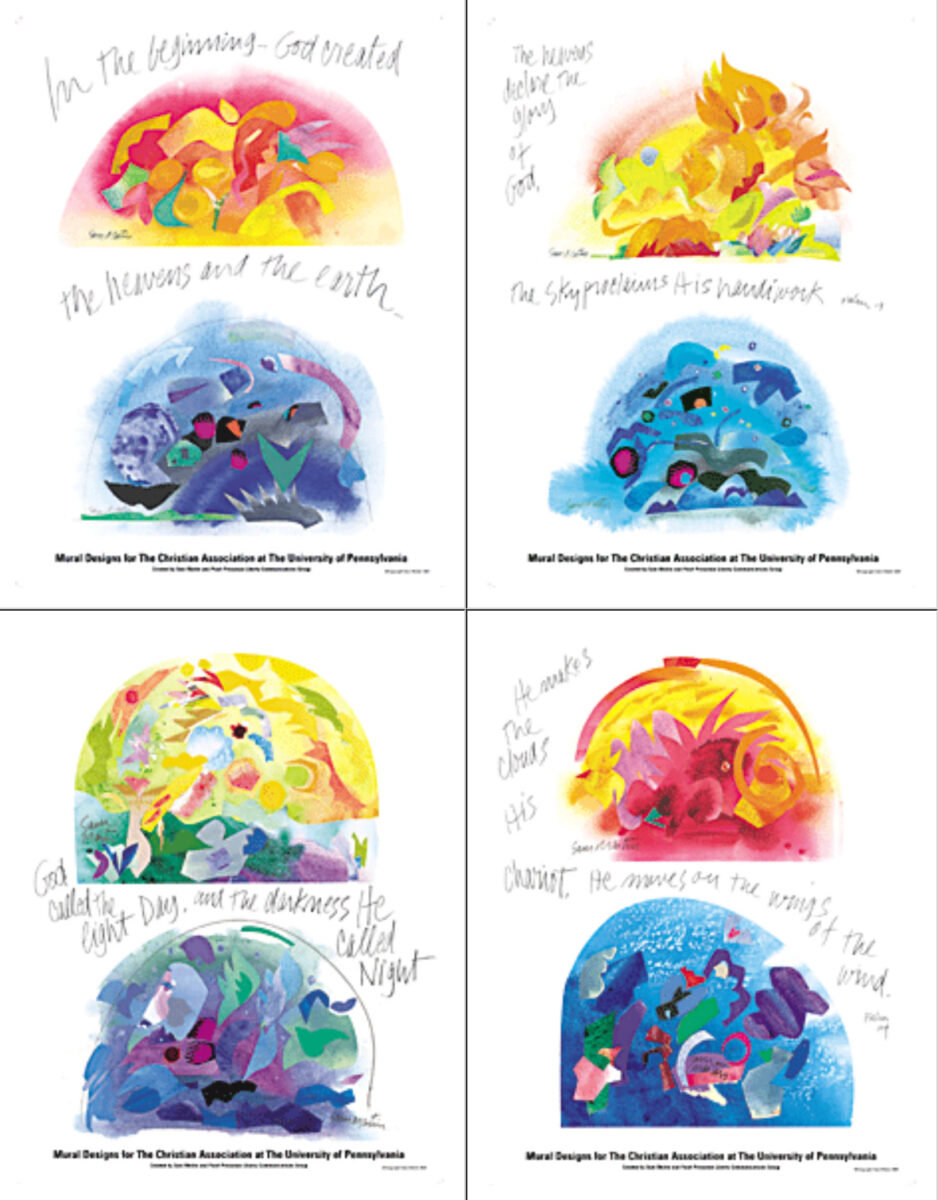

At the building’s formal dedication in February, where Maitin’s sketches for his new mural were on exhibit, the benediction before dinner was given by Rabbi Howard Alpert, executive director of Penn Hillel. “I find Sam and his work inspirational,” said Alpert. “His paintings based on Genesis and the Psalms express the highest aspirations of humanity.”

Hillel, the Newman Center, and the Christian Association are part of the Interfaith Council on campus, sharing a social-action agenda and participating in several joint projects, such as a Sunday night soup kitchen at Hillel for residents of West Philadelphia; and a Safety Fair, an annual event that attracts more than 1,000 children who come to learn about various personal-safety precautions. “Our joint mission is to raise awareness of spirituality though social action,” said Alpert.

Dr. Marjeanne Collins, professor emerita of pediatrics at Penn and a chair of the CA’s board, introduced Maitin at the dinner. Collins, who spearheaded the project for the new mural, said: “We love and respect Sam for living his life as he practiced his art. To use Sam’s words, he has always thought that ‘the making of art is a humanizing and sensitizing process, which, unlike most other activities, including formal religion, never isolates, separates, or threatens people.’ Rather, it is an attempt to contribute to society, to people, to civilization, forging bonds where none existed and creating a visual history that serves as an anchor for succeeding generations.”

Collins pointed out that the integration of Maitin’s philosophy of life and work is clearly shown by his prolific efforts on behalf of SANE, an organization that flourished in the 1970s and 1980s to combat nuclear testing. Maitin created many silkscreen print-posters honoring, among others, broadcaster Taylor Grant, actors Ed Asner and Jane Fonda, and Nobel Peace prize-winner Desmond Tutu. During the 1970s, Maitin also joined a group of artists and poets, including Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, who protested against the war in Vietnam. To that effort he contributed eight “peace posters.” Maitin believes that “poster art can be shared with numerous people because it is non-elitist.”

Philadelphians are particularly fond of Maitin, said Collins, because his paintings, murals, and sculptures decorate and brighten so many public places and spaces: the Fleisher Art Memorial, where he took painting lessons as a boy; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and other hospitals; Temple University Dental School; the Kaiserman Jewish Community Center in Haverford; the YM-YWHA at Broad and Pine Streets; the Free Library of Philadelphia; the Settlement Music School; the Philadelphia Art Alliance; Wills Eye Hospital; and the rear wall of the Academy of Music. He recently designed posters for the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Woodmere Art Museum in Chestnut Hill, which held a major retrospective of his art last year.

Maitin’s latest large-scale work is an 11- x 5-foot polychrome aluminum sculpture for George Washington University in Washington, D.C., which was commissioned by Philadelphia oncologist Dr. Luther W. Brady RES’56, a longtime Maitin benefactor. This spring, after a two-week stint as artist-in-residence at Brevard College in North Carolina, Maitin will resume working on another mural, commissioned by the Jewish Family and Children’s Service of Philadelphia, for the new Please Touch Museum, which will be located on the Delaware River waterfront.

He will also continue working up sketches for the new chapel mural. Maitin envisions two paintings, each 7- x 8-feet, on the east and west walls of the room. One will be in warm, sunny colors, suggesting light; the other in greens, blues, and purples, evoking darkness. “The arc-shaped windows gave me the idea to create similar mural shapes,” says Maitin, who would also like to do a small framed painting for the back wall, as well as a painting for the ceiling, so that when people come to pray they literally will be surrounded by light and color.

Unlike his earlier mural, Maitin wants the new ones to be a bit more vivid. “The two semi-circular shapes will bring to mind the shape of the world,” he explains. “I am thinking of Genesis, of Creation, as a theme, and I want to weave in the impressions I have of the 104th Psalm. It is one of my favorites. I used to discuss it with Ralph Moore. In a sense, God has finished his, or her, work and looks down at the earth and talks of the roar of the lion from the mountaintop; he cavorts with the leviathan of the sea—a huge sea monster I have always thought of as a whale. I don’t want them to be too literal. I’ll probably incorporate calligraphy, which is typical of me.” Maitin will “get some feedback from the folks at the CA” before executing the final designs. There is no deadline, but he hopes to finish the murals and install them by this fall.

“Although Sam does not think of himself as a religious man and is suspicious of organized religion, deploring orthodoxy and fanaticism,” says art reviewer and critic Rita Rosen Poley, who attended the dinner, “I believe that he is probably more religious than he thinks.” Poley curated a large show of Maitin’s religious works last year at the Temple Judea Museum at Congregation Keneseth Israel in Elkins Park. The show, which featured a series of biblical watercolors inspired by the 1976 Bar Mitzvah of his son Izak, was titled “The White Monkey Talks With God: Sam Maitin Paints From the Bible.” It included about 70 or 80 works by the “white monkey” (which is how Maitin’s uncle described him when he was born).

“When we were young, my brothers, my father, and I would have discussions about personalities in the Bible,” Maitin says. Poley thinks that Maitin’s childhood, filled with family conversations about historic, political, literary, and cultural Judaism, left an enduring legacy.

Like Ralph Moore and Beverly Dale, Maitin believes that music, art, and painting are the spiritual quests of the human heart and soul. “One reason I am doing this,” says Maitin of the murals, “is because I have a great affection for these people. They are truly the great people.” To show his support and appreciation, the artist designed four silkscreen posters, based on his mural designs for the new chapel, and donated them to the CA.

“We were really overwhelmed by Sam’s generosity,” says Marjeanne Collins. “We will use the posters to promote the Christian Association’s expanded program support for student and community outreach. And, of course, we hope it will attract many people to Sam’s Sistine Chapel.”

Jane Biberman, former editor of Inside magazine, profiled Sam Maitin for the Gazette in 1987. She is a freelance writer in Philadelphia.