It was embarrassment that drove Edward Lawler Jr. C’80 to investigate the strange situation of the President’s House in Philadelphia. He was giving a tour of the Independence Hall area to a relative about five years ago, and after explaining that Philadelphia had been the nation’s capital in the 1790s, he pointed out Congress Hall (where the House of Representatives and Senate met) and Old City Hall (where the U.S. Supreme Court met). The young man listened, then asked where the equivalent of the White House had been.

“I turned around and pointed to the ladies’ restroom next to the Liberty Bell Pavilion, and told him I thought it had stood there,” says Lawler, who prided himself on his knowledge of local history. “But it seemed odd that I didn’t know this for sure, that so important a building and site had been forgotten.”

The details of its commemoration are still being hashed out, but the fact that it is being commemorated at all is due largely to Lawler, the Independence Hall Association’s historian, who has invested countless hours into making the memory historically accurate.

Few buildings in America had the historical pedigree of the President’s House, which stood on the south side of Market (then known as High) Street, a block north of Independence Hall. Built in 1767 (and rebuilt in 1781 by Revolutionary financier Robert Morris), the handsome, four-story brick edifice was both the residence and executive mansion of the nation’s first two Presidents. George Washington lived there from November 1790 until March 1797, and presided over State dinners on Thursdays and public “levees” (audiences) on Tuesday afternoons. Living with him was his wife Martha and their white servants—and eight of their slaves, who were periodically “rotated out” of the state to avoid Pennsylvania’s anti-slavery law. Two escaped during their time in Philadelphia, and Washington signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 into law while living in the house. That law, notes Lawler, “gave teeth to the provisions of the Constitution which protected slavery, and had a chilling effect on the lives of the one-fifth of the American population which was of African descent.”

Native Americans enjoyed a slightly warmer welcome there, at least on one occasion. In a 1794 diary entry, John Quincy Adams described a reception given to a group of Chickasaw Indians by Washington, who joined them in smoking from a “large East Indian pipe.”

Three years later, Adams’ father, John, was elected the nation’s second president, and he and (sometimes) his wife Abigail lived there from late March of that year until May 1800. It was in the President’s House in December 1799 that they received the Senate “in a Body with a sympathetic address” mourning the death of Washington.

There were other famous residents of the house—which, before the Revolution, was owned by Richard Penn, grandson of William Penn and the brother of Thomas Penn, who helped fund the College of Philadelphia. One was British General William Howe, who lived there during the occupation of Philadelphia. Another was Major General Benedict Arnold, who made the house his residence and headquarters after the British evacuated the city in June 1778; it was there that he began his treasonous correspondence with the British.

The house was converted into a hotel in 1800, and on November 10 of that year, Abigail Adams stayed there en route to the new capital in the District of Columbia. She wrote to her sister: “Though the furniture and arrangment (sic) of the House is changed I feel more at home here than I should any where else in the city, and … I can scarcly (sic) persuade myself that tomorrow I must quit it, for an unknown & unseen abode.” That would be the White House.

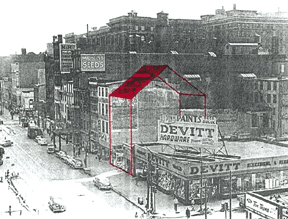

The house was gutted in 1832, and the memory of it faded. Though its side walls stood until the 1950s, the size, shape, and exact location had long been blurred by the conjectures of amateur historians.

In the 1930s, a WPA [Works Progress Administration] project assigned more than 40 people—historians, researchers, architects, woodworkers—to create a model of the President’s House. The idea was to generate enough interest to rebuild it, full-sized, in the proposed Independence National Historical Park.

“Unfortunately,” says Lawler, “the WPA researchers really blew it.” Though they created a gorgeous, carefully detailed model, it was of a “fictional five-bay house” that had been conjured up by a 19th-century amateur historian. To add insult to injury, the WPA somehow “missed the fact that the four-story side walls of the house were still standing, right there in front of everyone.”

A rebuilt President’s House could have become “as familiar a sight (and a site) as the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg,” Lawler adds wistfully. “Instead, a public toilet was built atop the footprint of the house.”

Fast-forward again to the late 1990s. A month after Lawler gave that eye-opening tour to his relative, Independence National Historical Park began a series of public meetings about the proposed changes to Independence Mall, which included a new Visitors Center, a new home for the Liberty Bell, and the National Constitution Center [“The House That Joe Built,” November/December]. Lawler was one of three citizens who urged that the President’s House be commemorated in some fashion.

“The Park’s response was unenthusiastic (to say the least), so I decided to begin researching it on my own,” he recalls. “It started as a puzzle, to figure out just exactly what the President’s House had looked like when Washington and Adams occupied it, hoping that the work would help Independence Park to commemorate the house. I have a big collection of Philadelphia books from my father and grandfather, both Penn grads, and the more research I did on the house the more confusing things became.”

The efforts to establish the truth and commemorate the President’s House and its early inhabitants can be found on the Independence Hall Association’s Web site (www.ushistory.org/ presidentshouse). But at least there is a consensus that the “footprint” of the house should be outlined in the paving of the entrance plaza to the Liberty Bell Center, and that the eight slaves will be commemorated—though exactly how remains under discussion.

If it’s been an often-frustrating project for Lawler, it’s also been enormously rewarding.

“The most satisfying aspect of the project has been reconstructing the lives of the eight enslaved African Americans who Washington brought to Philadelphia to work in the presidential household: Giles, Paris, and Austin, who worked in the stables; Hercules, who was the primary cook, and his son, Richmond, who helped in the kitchen; Moll, who cared for Martha Washington’s two grandchildren; Christopher Sheels, who was Washington’s body servant; and Oney Judge, who was Martha’s body servant,” says Lawler. “In the past, they’ve been largely a list of names; I’ve tried to gather personal anecdotes and biographical information to help turn them back into real people.”

The moving story of Oney Judge’s escape to New Hampshire—and Washington’s requests to have her seized and returned —can be found on the Web site, as can thumbnail sketches of the other slaves. The site also features a number of letters and memoirs written by visitors to the house.

“From the first, I realized that the story of the house had to be told through first-person accounts at the site,” says Lawler. “Thousands of people visited the house in the 1790s, and I was certain that many would have written home about what it was like to attend a State dinner, or a presidential audience, which were called levees. There is also the correspondence of the people who lived in the house, especially Washington and his chief secretary, Tobias Lear, and John and Abigail Adams, who were extensive writers.”

Asked if he’d ever wanted to go back and tweak history a little, Lawler responds: “Oh, yeah. I’d like to go back to the 1930s, correct the WPA’s colossal mistakes, and shout the opposite of what Reagan said to Gorbachev: ‘Don’t tear down these walls!’”

—S.H.