More than most authors, Lawrence Weschler knows that there are two kinds of reading. His latest book, Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences, began as a contest on his publisher’s website before taking form in ink and paper. In March, the former New Yorker staff writer came to the Penn Humanities Forum to “worry out” some of the differences between printed books and reading on the Web.

Weschler has nothing against the Web. He began his presentation with a series of his favorite YouTube videos. But as a devotee of long-form writing with almost a dozen books to his name, he’s cautious about the effervescent, distracted nature of the medium. The virtual realm is dominated by what he terms the “frenzy of rebound,” as readers’ attention spans are tugged this way and that by beckoning hyperlinks. “Cruising the Web might be likened to musical improvisation,” he said during his talk, “but a book is a score.” The analogies did not stop there. Here is an abridged passage from his lecture.

Roy Blount recently commented that reading from a monitor instead of a book is like playing videogame football instead of throwing the ball around. What’s so funny about that is it used to be that reading a book about football, as opposed to actually playing football, was the analogy—“stop being such a reader, and go and play.”

But it seems to me that he’s making a point, that book-reading is active. It exercises different muscles, demands a different stance, a different posture towards what’s going on, than the Web does. I might summarize it as “concentration” versus “scatter.” Or, in a sense, that reading is centripetal, and the Web is centrifugal. That reading is drawing you into the book, and the Web is continuing to hurl you out onto other things that are just outside, just beyond. Reading [a book] involves entering into a dialogue with one other person, on the other side of the page, where the Web is a kind of flirtage with many.

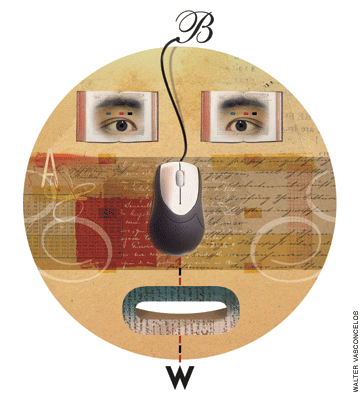

Continuing this notion of reader’s experience, I would describe the difference between vertebrate and invertebrate. The Web is invertebrate. Books, on the other hand, are vertebrate; they have spines. They have spines that open out to us, and we hold onto them, and they hold onto us, in a kind of enfolding embrace while you are in them. Rilke’s great line about “that love that consists in this: that two solitudes protect, abut, and greet each other.” That sense of your solitude, and the solitude of the thing that you’re reading.

Books that possess us are books that we want to posses. Borges has a great story where he says, “A man sets out to draw the world. As the years go by, he peoples a space with images of provinces: kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, instruments, stars, horses, and individuals. A short time before he dies, he discovers that the patient labyrinth of lines traces the lineaments of his own face.”

It seems to me that that’s true of a book-lover’s shelf. That the shelf, when you die, is, in a very profound sense, you. And that doesn’t happen on the Web.

—Sean Whiteman LPS’11