Juan Castrillón, a PhD candidate in ethnomusicology, didn’t develop the online version of his exhibit Re-Covering the Ney Collection with any premonition that right now, millions of people would be confined to their homes not only in Philadelphia, but throughout the country and world.

But as it turns out, his pre-planned web exhibit has become one of the limited opportunities to visit a museum right now—prompting professors to assign it to their students, and enticing people from all over to scroll their way through a virtual trip.

Originally on display at the since-closed Van Pelt Library—but also open for visits online anytime here—Re-Covering the Ney showcases four reed-flute instruments (neys) that have lived in the Penn Museum’s African collections since the late 19th century. Castrillón says there is no certain dating of these particular neys, but he suspects they range from the 17th century to the end of the 19th century.

The ney as an instrument goes back much further than that. In excavating the ancient city of Ur, Penn archaeologists found what are likely the oldest versions of the ney. Penn Museum houses one of them, dating back to 2,800 B.C., in its Near East collection.

In 2001, Castrillón was studying anthropology as an undergraduate student in Colombia when his teacher popped in a cassette tape of someone playing the ney. He still remembers that moment. “I was just grabbed and hooked,” he says. “I felt as if I were home when I listened to that sound.

“I was so intrigued by that feeling,” he continues. “When someone plays a trumpet, we feel that the sound comes out of the trumpet. With this instrument, I felt like the sound was going back to the instrument. For me, the only way I had to express that was using metaphors about introspection or meditation.”

Soon Castrillón was studying the ney as a researcher while also learning to play it himself. He’s now made numerous trips to Istanbul to take ney classes and perform anthropological and enthomusicological studies on the instrument, which is especially popular in Turkish classical music. Though Castrillón is careful to note that the ney is not considered a sacred instrument, he quickly adds that “what is sacred, or has a spiritual connection, is the attitude that a performer expresses through the instrument.”

He was in Istanbul conducting field work and shooting a film about the ney when he heard from Dwaune Latimer, who supervises the Penn Museum’s African collections. She’d been fielding requests for information on the museum’s neys and, as Castrillón writes in the virtual exhibit text, “This exhibit presents my answer to Dwaune Latimer and anyone interested in what these instruments have to tell.”

After years of study, Castrillón ranks the ney as the most difficult instrument to play. It’s not like a recorder, where you have a mouthpiece to blow into. It’s also not like a modern flute, in which solid keys help cover the instrument’s holes for you. The ney is end-blown and made from a single reed, which means it requires a lot of air. To produce quarter-tones and eighth-tones, a player must cover portions of its holes just right with their fingers.

“Producing the sound takes a lot of time,” Castrillón says—often weeks of practice just to play a single note. “Many people who start trying to perform on the ney grow frustrated so quickly. They want to learn quickly and play tunes. With the ney, it’s a very long process.” (Unable to resist trying for yourself? You can actually buy a ney right on Amazon.)

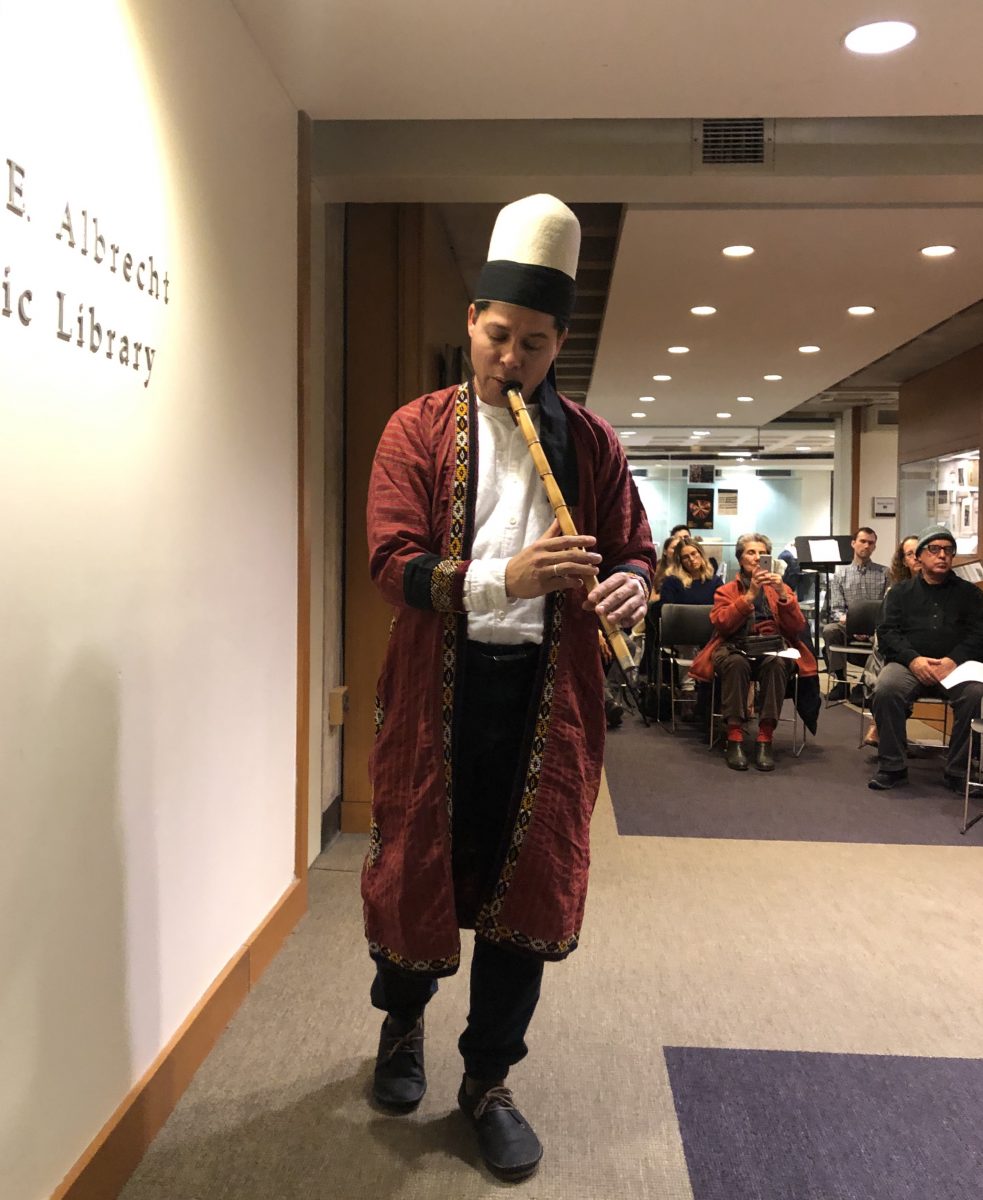

Along with photos and write-ups, Castrillón’s virtual exhibit includes several videos—from interviews with the head of Penn’s music library and Latimer, to footage he shot in Istanbul, to his own performance on the ney inside Van Pelt last December:

—Molly Petrilla C’06