Drew Gilpin Faust examines her own youthful journey from the Virginia gentry to New Left activism with a practiced historian’s eye—but stops short of probing her adult trajectory into another elite establishment.

By Maureen Corrigan

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 320 pages, $30.00

“How did you become radicalized?” That’s the question the late Todd Gitlin—the New Left activist, scholar, and former president of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)—once asked me at a board meeting of the long defunct “Progressive Book Club.” (I’ve since learned that Gitlin often asked that question of people.) My stumbling deflection must have disappointed him. A “radical” in my conservative corner of the 1960s was a high-schooler who attended Up With People concerts, which promoted a cheery vision of multiculturalism, instead of joining the local chapter of Young Americans For Freedom, as several of my classmates did.

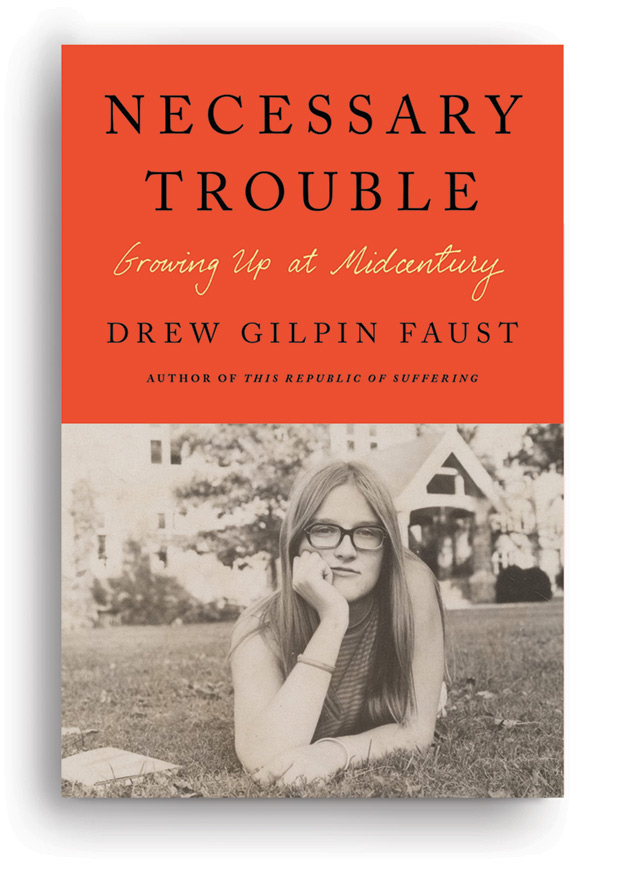

Drew Gilpin Faust’s new memoir, Necessary Trouble, offers the kind of response that Gitlin was no doubt expecting from me. Faust—who was the Walter Annenberg Professor of History at Penn before serving as the founding dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in 2001 and becoming the first female president of Harvard University from 2007 to 2018—chronicles her journey from a privileged post-World War II childhood on her family’s horse farm in segregated Virginia to gradually “becoming radicalized” in high school and joining SDS in 1964, her first year at Bryn Mawr College. (Necessary Trouble includes a photo of Faust’s original 25-cent copy of The Port Huron Statement, the founding document of SDS.) Galvanized by televised footage of the vicious “Bloody Sunday” attack on John Lewis and other protesters attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, 1965, Faust forsook her midterm exams at Bryn Mawr and drove with a college boyfriend in a borrowed car to Alabama, where they joined in the historic voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery led by Martin Luther King Jr. Faust writes at the end of Necessary Trouble that, in a conversation a few months before Lewis died in 2020, he blessed her use of his signature phrase for her own memoir—which, however, places a burden on the text that it understandably can’t bear.

Like other memoirs written by Americans who became activists during the early 1960s, Necessary Trouble tells the inspiring story of an individual life intersecting with History—in this case, the civil rights and burgeoning anti-war movements, as well as the Sexual Revolution. What distinguishes Faust’s account from a contemporaneous “awakening-into-activism” account like Ann Moody’s Coming of Age in Mississippi is not so much the arc of her narrative but, rather, the dispassionate style in which she chronicles it from the perspective of a halfcentury later.As befits a distinguished historian whose 2008 book This Republic of Suffering [“Arts,” Mar|Apr 2008] won the Bancroft Prize and was a finalist for both the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, Faust has written a charged memoir about the ’60s, but not of the ’60s.

“As a historian,” she writes in the book’s prologue, “I have spent much of my life listening to voices from the past and trying to use them as bridges of understanding to times distant from our own. Here I am seeking to be one of those voices … History is about choices and about how individuals make those choices within the structures and circumstances in which they find themselves. I want to illuminate what those choices looked like to one girl trying to become a person during two decades of rapid transformation and powerful reaction in American life.”

Accordingly, Faust generally opts for the informed wide view, rather than intimate confidences. This is a memoir augmented by statistics on women’s higher education in the early 20th century, changing post-New Deal income tax rates for the wealthy, and capsule social histories. For example: broaching the subject of shifting attitudes toward premarital sex at Bryn Mawr, which she entered in 1964, Faust offers a brief background on the Pill, which became available in 1957, but was not accessible to “unmarried minors without parental consent” until the late ’60s. As a teenager, Faust was prescribed the Pill to treat her irregular and painful periods. Consequently, she says, “I never had to worry about getting pregnant.” The door then closes on that subject.

Necessary Trouble richly—if selectively—chronicles Faust’s family history and her own life and times up to her graduation from Bryn Mawr in 1968. The memoir opens on tragedy: the death of her mother on Christmas Eve 1966 from what Faust suspects may have been adult anorexia. Faust’s uncertainty derives from the silence that shrouded “anything difficult or unpleasant” in her family. Both her parents, who met and married during World War II, came from affluent families who belonged to the “horse set.” Faust’s grandfather bred and sold thoroughbreds and racehorses; her father attended Princeton and “looked as if he had been invented by F. Scott Fitzgerald.” (A photo in this memoir from a 1940 Esquire article on “collegiate fashion” bears out this claim.)

Faust observes that her mother, a transplant to the South who was “deeply unhappy in 1950s Virginia,” focused her considerable energies on her three children, particularly her bookish only daughter, Drew, who resisted training to “be a lady.” About her mother’s life and early death, Faust starkly observes, “Few could have done better at achieving what [Betty] Friedan called ‘the forfeited self.’ She would live through her children even as they struggled to escape her control. Her death … was a final act of self-abnegation.”

Faust would also part ways with her family over the issue of racism. If her parents accommodated the racial status quo in segregated Virginia, Faust pushed back remarkably early. In 1957, as Virginia Senator Harry Byrd called for “Massive Resistance” against plans to desegregate public schools, the nine-year-old Drew Faust wrote a letter to President Eisenhower sharing her “many feelings about segregation.” For a historian of the Civil War era who would go on to comb through thousands of archival letters in the course of her research, Faust understandably was delighted to discover that her elementary school letter “now rests among twenty-three million pages of manuscripts in the Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kansas.”

Higher education—boarding school and Bryn Mawr—was Faust’s pathway to a wider world. (She also credits books featuring fictional and real “girls who dare”—like Nancy Drew, Scout Finch, and Anne Frank—as a deep influence.) The Bryn Mawr that Faust entered in the mid-1960s was an intellectually rigorous institution marked by “a very peculiar sort of feminism”: one in which the students were seen as every bit the equal of a man, yet to “even speak of women as a category was seen as a kind of special pleading, an acknowledgment not so much of difference as of deficiency.” (Disclosure: for several years in the 1980s, I taught English at Bryn Mawr and worked in the president’s office. By that time, Women’s Studies was in its ascendency.)

The ethos of “participatory democracy” that Faust embraced by, for instance, volunteering with other students to go door-to-door in economically-distressed South Philly to discuss community issues as part of the SDS-sponsored “Economic Research and Action Project”—“We had no idea what we were doing,” Faust confesses—also transformed life at Bryn Mawr. Faust describes a surreal meeting with the Board of Trustees in Atlantic City—as the Miss America Pageant was underway, no less—where she and other members of student government successfully argued for the abolishment of antiquated curfews and “parietal rules” designed to safeguard the virtue of female undergraduates. The Sexual Revolution had officially arrived.

When Faust became the president of Harvard, she ascended to an Olympian position within the institutional elite of American society. Perhaps the most frustrating gap in this perceptive, yet distant memoir is thatreaders cannot infer any clues as to how Faust subsequently navigated the winding path from New Leftist to establishment eminence.Faust mentions that, shortly before his death in 2022, she and Todd Gitlin corresponded about Camus and his influence on the New Left. In invoking Gitlin and Camus, Faust implicitly points to issues of power within social hierarchies—the radicalizing analysis of her youth—that make one curious about her later life.Several years earlier, when she was still serving as Harvard’s president, Faust found herself in conflict with her former SDS compatriot, who was leading alumni and students at Harvard and Columbia, respectively, in fossil fuel divestment movements. During her tenure, she was, at best, indifferent to the organizing of mostly female workers at a Harvard-owned hotel. If Faust writes a sequel to Necessary Trouble about her professional life as a historian and college president,it would be revealing and powerful for her to go from the question of “How did you become radicalized?” to “How does a young woman sustain her impulses to transform the world?” even as her gifts, worldly ambition, and the advantages of her class origins ultimately take her from the streets to the suites.

Maureen Corrigan Gr’87 is the book critic for the NPR program Fresh Air and the Nicky and Jamie Grant Distinguished Professor of the Practice in Literary Criticism at Georgetown University.