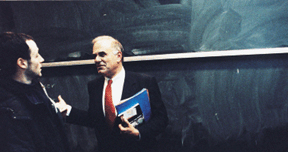

Most faculty don’t have students waiting for a turn to shake their hands after the first class of the semester, but when you’ve just finished two successful terms as the top office-holder in Philadelphia, you can expect this kind of reception. So when Edward G. Rendell C’65 dismissed the first session of “The Science of Politics: Who Gets Elected and Why?” before the allotted hour, many students lingered to meet the man dubbed “America’s mayor.”

Sporting a dark business suit, but also the relaxed expression of one who has just returned from a week in Hawaii with his family, Rendell swept into a Logan Hall classroom the evening of Jan. 17 for the second of two three-hour classes he will be teaching in the urban-studies department each week. A few of the 75 gathered students (many of whom weren’t registered, but were vying for admission) clapped softly as he bypassed the imposing lectern and briefly conferred with his graduate assistant at a nearby desk. As he removed his glasses and stood up to address the class, one briefly wondered whether the man who rescued Philadelphia from fiscal crisis eight years ago could also finesse the transition from City Hall to Locust Walk. But the politician-turned-instructor left little doubt when he explained that he had conducted some market research before the semester began, consulting his son Jesse, a sophomore at Penn.

“He gave me two pieces of advice: … One, keep everyone here for about 20 minutes. Second, if you hand out reading assignments, tell everyone in advance what portion of the articles they really should read. [Because] nobody reads all of this stuff.’

“We’re not going to do that,” Rendell added, but he vowed to make the readings—and the course—relevant. “We do want this to be a fun class where people ask questions and challenge [graduate assistant] Margaret [Pugh] and challenge myself.”

With no tests planned, students’ grades will be largely based on their work in assigned teams on mock political campaigns. Rendell told them they would sink or swim together, because that’s what happens in a race. Laying out the challenges of their assignment, he said, “You don’t know what the other candidates are going to do, and you’re going to be asked to anticipate their reactions. It’s very much like a chess game.”

Rendell, inarguably, has become a master of the game since he last taught a similar course on campus about a dozen years ago. And now, after his recent appointment as the chair of the Democratic National Committee, he will no doubt be acquiring a set of new moves. But, as he explained after class, he doesn’t plan to divulge presidential campaign secrets along the way. “I don’t think I will talk about any ongoing problems any more than I would have had I just been elected mayor—although it’s interesting, my role as DNC chair has taught me a lot about federal elections, which I wasn’t nearly as conversant in before.” For behind-the-scenes insight into the 2000 campaign, students will have to wait for another semester. Rendell plans to teach again in 2001.

The former mayor’s campus duties began earlier in the day, with a much smaller seminar entitled, “Can Cities Survive?” made up predominantly of undergraduates who plan to pursue public-service careers. “The level of commitment of the students there was very strong,” he observed. Though the politics course is geared toward a more general student audience, he added, “I was even impressed with the discourse here.”

In a brief introduction to “The Science of Politics,” Rendell shared anecdotes from previous campaigns, including his first race for district attorney, his unsuccessful bid for Pennsylvania governor in the eighties and the Democratic party’s push last fall to get the vote out for John Street in his tight mayoral race against Republican Sam Katz.

He also touched upon a number of the topics that will be covered in greater detail this semester, such as fundraising, the shrinking influence of political parties, the effectiveness of field workers and, especially, the role of the media.

“When I ran for DA for the first time, I got elected because of the free media,” Rendell said. He recalled one press conference he staged to rail against his incumbent opponent for a junket to Montreal. Among the expenses charged to city taxpayers from that trip was a $168 safari suit. So Rendell waved a similar outfit before the TV cameras. “In some ways,” he explained, “free media is almost better than paid media, because people get a little inured to those paid commercials.”

It wasn’t until his gubernatorial race, however, that Rendell learned how naïve he had been about media coverage.

To help him appreciate the differences in news markets across the state, his media consultant at the time would pretend to interview him. Assuming the role of a television reporter in socially conservative northeastern Pennsylvania, for example, the consultant asked, “Should abortion be legal?”

Recalls Rendell, “I gave a 25-to-30-to-35 second sound-bite about why I thought abortion should be legal. He said, … No, that’s a terrible answer. It’s absolutely calculated to allow them to run that on TV tonight, because you gave them 30 seconds, exactly what they were looking for. Your answer should have been ‘Yes.’ And if they pressed it, … That’s the way I feel.’ The reason being that they can’t put that on TV.

“The second question they ask you is, … Do you believe in the death penalty?’” Rendell had a record as district attorney to prove that he did. “Then you give them a 30-second answer,” the consultant told him. “That’s the question that goes on the news that night.”

But Rendell underscored the difference between campaigning effectively on one’s beliefs and letting public polls dominate the discourse. “One of the things I disliked in Sam Katz’s [mayoral] campaign,” he observed, “was that his media consultant was enunciating positions in the last six to seven weeks that were straight out of the polls.” Katz took a jab, for instance, at the Philadelphia Parking Authority—a long-reviled agency that Rendell takes credit for revamping. “That came right out of a poll,” said Rendell. “The public perception had not yet caught up to the reality. You have to draw the line somewhere and say, ‘I’m not going to do that. It may poll well, but it’s wrong.’ I think that’s your responsibility as a candidate.”