In his brief and dramatic life, 19th-century medical alumnus Elisha Kent Kane broke new ground in exploring both the frozen North and the hothouse atmosphere of celebrity culture.

By Dennis Drabelle

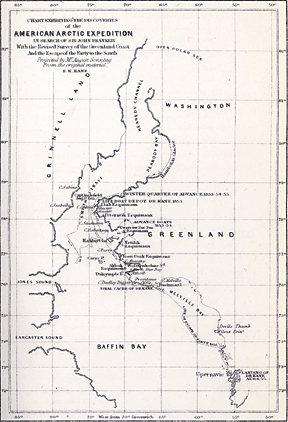

A man you’ve probably never heard of was once the most famous living American other than statesmen and generals: Dr. Elisha Kent Kane M1842, who flourished in the years between the death of the last remaining Founding Fathers and the onset of the Civil War. Kane deserved the attention he got, for his exploits changed the national orientation. Before him, America had been an object of exploration; with his travels, the new nation became an exploring agent, making its first significant contribution to knowledge of the outer world. He wrote his adventures down so appealingly that the typical 19th-century parlor was said to display at least two books: a Bible and Kane’s Arctic Explorations. (The Bible promised eternal salvation; the Explorations delivered national pride.) Two geographical features bear his name. One of them he explored: Kane Basin, between Greenland and Ellesmere Island. The other he didn’t and couldn’t have: Kane Crater, on the moon, about which all one needs to know is that it’s huge.

Kane himself might have stepped out of a boy’s adventure tale. He swung down into a volcano at the end of a rope, won a battle in the Mexican-American War, stayed poised when faced with mutiny under his command, and pointed the way to the North Pole.

His private life was equally flashy. Foreshadowing the tendency of well-known people to mate with each other and become well-known-squared, Kane courted and married the most famous woman of the day, the spiritualist Margaretta (Maggie) Fox. Their love affair was repeatedly tampered with by distant forces: the punishing Arctic and the nebulous region where souls hover after death. At times the principals themselves were hard-put to sort out their genuine mutual affection from the expectations raised by their public personae. In common with so many famous folk to come, they carried on a kind of ménage a trois: a man, a woman, and the limelight.

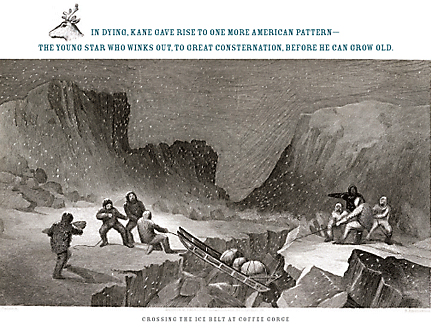

While all this was going on, a crucial fact about Kane was little known. From his late teens on, he was under a medical sentence of death. His response was to live at breakneck speed, piling up feats in a short span of years. Sometimes he went too fast—his expeditions were marred by impulsive decisions, unrest, and near-disasters—but he felt he had little choice. When he was 37, the dire warning came true, and a nation on the verge of sectional division pulled itself together for an unprecedented bout of mourning. In dying, Kane gave rise to one more American pattern—the young star who winks out, to great consternation, before he can grow old.

Born in 1820, the eldest son of prominent parents (his father was a federal judge in Philadelphia), Kane was short and slender, with fine features, impeccable manners, and a rebellious streak. His rush to glory began when he was a freshman at the University of Virginia. He contracted rheumatic fever, a disease that attacks the lining of the heart. In his case, the damage was so severe that a doctor told him he could die “as suddenly as a musket shot.” He fell into a protracted depression. A remark by his father brought him around: “Elisha, if you must die, die in the harness.”

From then on, the young man lived with a sense of urgency: much to do, not much time to do it in. At Penn’s medical school, he was considered the brightest student in his class. After graduation, he wasted no time. With his father’s help, he wangled a job as medical officer for a diplomatic mission to China. On holiday in the Philippines, he performed his first great stunt. Tethered to a rope held by guides, he swung down into a live volcano to collect a sample of sulphur water. Local pygmies gave this exploit a Tarzan-of-the-Apes twist by raging against the insult to the volcano’s indwelling god.

After a tour of duty in the navy, Kane went to Washington, hoping to pull more strings. There he probably made contact with a fellow Pennsylvania native, Secretary of State James Buchanan. The young man’s timing couldn’t have been better. The United States was at war with Mexico, and President Polk wanted to smuggle a message to his commanding general in the field, Winfield Scott. Kane got—and successfully performed—the assignment. Then, attached to a scouting party in Mexico, he made another splash: In a fight with sabers, lances, and guns, he not only routed the opponents but also patched up the wounded, including himself. On his return to Philadelphia, he was greeted as a hero.

Next he was off to the Arctic. This phase of Kane’s life, which began in 1850 and lasted until the end, was occasioned by the disappearance of English explorer Sir John Franklin while searching for the elusive Northwest Passage. Under Franklin’s command, two ships had set sail in 1845; nothing had been heard from them since. The First U.S. Grinnell Expedition, to which Kane was detailed as surgeon, failed to find the missing Brits, but Kane came back infatuated with the Arctic. The account he wrote of the voyage was a warm-up for his later masterpiece about his own expedition.

While Kane was reconnoitering the top of the world, his future wife was trafficking with ghosts. Maggie Fox came from a humble background in rural upstate New York. At home one night in 1848, she and her sister Katy noticed that they had extraordinarily flexible toes, which they could snap smartly against one another inside their shoes. Their superstitious mother concluded that a spirit was making these “rappings,” which contained messages her girls could decipher. Maggie and Katy played along, and soon they were the talk of the neighborhood.

An older sister smelled money; under her tutelage, Maggie and Katy created the séance, a quasi-religious service in which anyone who paid a fee could get in touch with departed loved ones. Elsewhere, opportunists discovered that they, too, could carry messages between the living and the dead, as well as produce more elaborate effects, such as apparitions and musical instruments that played themselves. Spiritualism became an international craze. (For more on Maggie Fox, spiritualism, and Penn’s connection with both, see “Feet and Faith” in the Mar|Apr 2006 Gazette.)

Katy was the prettier of the rapping sisters, Maggie the livelier. When they played Philadelphia in 1852 and a local hero came calling, it was Maggie he fell for. But if Maggie’s visibility as a medium had first brought her to Kane’s notice, he soon set her straight: not only did he not believe in spiritualism, he considered it vulgar. (In this he was hardly alone: Almost from the start, skeptics had noted a disparity between ends and means. If spirits had wisdom to impart about the great mystery of what happens after death, why stoop to such frivolous mechanisms as “rappings” and self-tooting horns?) Kane’s family expected him to marry within his own upper-middle class. He declared himself ready to defy them and wed Maggie, but only if she gave up spiritualism.

Maggie was both thrilled and peeved. Kane could be charming and generous, and it was flattering to be wooed by such a gent. But she didn’t like being condescended to, especially by someone about to abandon her for another Franklin search, this time as commander. Besides, she had family pressures of her own to deal with: Thanks to séance money, the Foxes had embraced a high standard of living.

By now Kane had become a performer himself, spreading his fame and raising money for his voyages by lecturing. He must have been a spellbinder: after hearing him give a talk, the English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray turned to a companion and said, “Do you think the doctor would permit me to kneel down and lick his boots?”

In a moment of candor, Kane admitted that he and Maggie were a pair of operators. “When I think of you, dear darling,” he wrote to her, “wasting your time and youth and conscience for a few paltry dollars, and think of the crowds who come nightly to hear of the wild stories of the frozen north, I sometimes feel that we are not so far removed after all. My brain and your body are each the sources of attraction, and I confess that there is not so much difference.” Mrs. Fox tried to keep the lovers apart, but they considered themselves engaged. Before returning to the Arctic, Kane took a drastic step: to remove Maggie from her family’s influence, he sequestered her with friends of his outside Philadelphia, where she began to receive the education she’d missed out on.

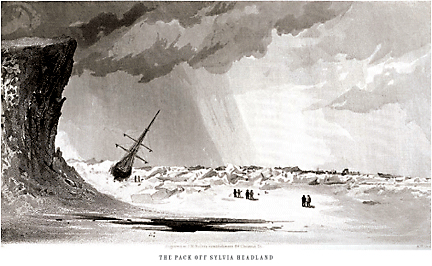

Back in his element with the clock ticking, Kane had little use for caution. Where a more deliberate explorer might hug the shores of a bay, Kane would steer between lunging icebergs in the main channel. But he learned from his mistakes and took advice from local Eskimos, which is more than can be said for many later explorers.

Though Kane and company were gone more than two years, this second attempt to track down Franklin was a true voyage for only a few months. The rest of the time, the ship was stuck fast in ice. The men stripped its interior of wood to burn in the stoves and fought against scurvy by consuming the few birds and marine mammals they managed to kill. Kane, who might have been thought especially vulnerable because of his weakness, was the only traveler to escape the disease—fresh meat can be preventive, there was a ready source on board, but he couldn’t get anyone else to join him for a bowl of rat soup. When the men felt up to it, they explored. One party got stranded and sent a man back for help. The fellow arrived so weak and addled that he couldn’t remember where he’d left his comrades, but Kane and other volunteers went out and found them anyway.

What Kane could not do was keep his men in line. Unrelenting winter darkness, temperatures that bottomed out at 69 degrees below zero, illness, boredom, being cooped up with the same people for months on end—so much cumulative misery tested the crew’s resolve. Some of them cracked, announcing their intention to abandon the marooned ship and strike out for civilization. For all of Kane’s shaky leadership, he handled the mutiny well. He gave everyone a choice, contained his fury when some of those he relied on most raised their hands to leave, talked a few into reconsidering, and grubstaked those who insisted on going. Four months later, when the deserters came straggling back, he honored his pledge to accept them.

The Second Grinnell Expedition, as it was called, found no trace of Franklin (he and his party had long since perished on a Canadian island), but it did lay down a route toward the North Pole. In the spring of 1855, Kane and his men abandoned ship and crept south in sledges and boats. Eighty-four harrowing days later, they reached an Eskimo settlement, where a Danish supply vessel took them on board. The expedition was a mélange of stumbles and regained balance, of mutiny and forgiveness, of gruesome weather and excruciating hardship, of exhilarating beauty and courageous enterprise—and Kane had it all down in journal entries and sketches, which he couldn’t wait to turn into a book.

On October 11, 1855, the forts of New York City fired cannons to welcome back Kane and his crew. The longsuffering Maggie Fox, in town on a visit, expected her man to pay a call that evening. She waited up for him till midnight, but in vain. He stopped by the next day, only to drop a bombshell. His family was adamant: He couldn’t marry her. He asked her to sign a statement denying that they were engaged, which she did. A few days later, he found the courage to return, hand the paper over, and watch as Fox tore it up.

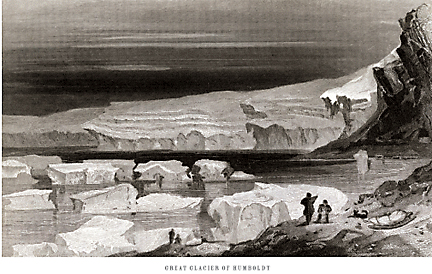

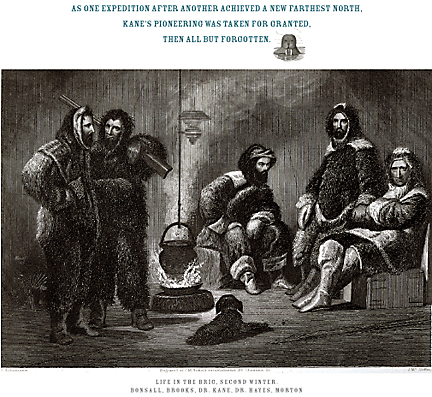

Having returned to Philadelphia, Kane flung himself into the writing of his new book, which he finished in a matter of months. Arctic Explorations: The Second Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin, 1853, ’54, ’55 was a sumptuous production, embellished with steel engravings based on Kane’s sketches—several of which are reproduced here—and enlivened by his vivid prose. “The thermometer had fallen . . . to -49.3,” he wrote of one outing, “and the wind was setting in sharply from the northwest. It was out of the question to halt: it required brisk exercise to keep us from freezing. I could not even melt ice for water; and, at these temperatures, any resort to snow for the purpose of allaying thirst was followed by bloody lips and tongue: it burnt like caustic.” Sales of the two-volume set topped 65,000 in the first year alone.

But the strain of writing at top speed undermined the author’s already fragile health. Lady Franklin, Sir John’s indefatigable wife, implored Kane to lead one last search for her husband. This was beyond him now, but he agreed to join her in England, where they would plan an expedition to be commanded by someone else.

At Kane’s insistence, Fox had sworn off spiritualism—a renunciation made easier because she feared being unmasked as a charlatan. Here, again, the lovers were kindred spirits; for Kane was a faker, too—a weakling passing himself off as a swashbuckler. Had the public scrutinized his second Arctic expedition more closely, they might have noticed what a squeaker it was: Three of his 20 men died, and the ultimate retreat could easily have ended in disaster.

The two illusionists considered themselves re-engaged. Only days before he sailed for England, they called in witnesses and said impromptu vows. Assuring Fox that this was a valid marriage, Kane promised they would do it over, formally and in church, when he returned. They seem not to have consummated the marriage before he left, but Kane’s will included a special bequest of $5,000 to his brother Robert, intended for Fox in case of her husband’s death.

Kane had to cut short his stay in England. His condition had worsened, and a warm climate was prescribed. He traveled to Cuba, where on February 16, 1857, he died. Grief was so urgent and widespread that the roundabout process of transporting his remains to Philadelphia developed into a new phenomenon: the multi-city funeral procession, by boat and barge and train and carriage, with the route lined by mourners—a precursor to the rites for Abraham Lincoln eight years later.

After Elisha’s death, the Kanes rallied around his memory. In particular, they tried to shield him from the taint of spiritualism, as personified by Maggie Fox. They refused to credit the marriage and balked at paying her the earmarked money. Only 22 years old, Fox was left in an awkward position. Calling herself Mrs. Kane, she built a shrine to the explorer in her bedroom and repeatedly asked his friends if he’d left any messages for her. He hadn’t. She begged Robert Kane for her bequest, which he doled out in dribs. She sued, but the case was dismissed, and the Kanes stopped payment altogether. Deepening the insult, the family fed information about Elisha to a friend who wrote an adoring biography—without giving Fox so much as a mention.

To vindicate herself—and make some money—Fox authorized publication of The Love-Life of Dr. Kane, a collection of Elisha’s letters to her. But her timing was off: The book came out in 1866, by which point the once-glamorous couple was old news, and it sold poorly. To support herself, Fox went back to work as a medium. In 1893, not quite 60, she died broke.

For a while, Kane fared better. Other explorers followed his route; he was given that lunar honor; and he and his voyage were still talked about—Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner cited him in their novel The Gilded Age (1873) as epitomizing a type of famous man: the leader of “some daring expedition.” But as one expedition after another achieved a new Farthest North, Kane’s pioneering was taken for granted, then all but forgotten. It didn’t help that Kane had been wrong about what he’d accomplished: He thought he’d found the fabled Open Polar Sea, an ice-free route straight to the Pole. But later explorers discovered there’s no such thing (or, rather, was no such thing—as global warming continues to scramble the atmosphere, Kane may turn out to have been simply ahead of his time).

Early in the 20th century, the race to the Pole gave rise to banner headlines: Which American was the first man to have stood on the numinous spot, everyone wanted to know, Frederick Cook or Robert Peary? With each scoffing at the other’s claim, someone had to be lying. Congress and the National Geographic Society weighed in, and the public couldn’t get enough of the controversy, which lingers to this day (Cook’s stock is currently up, while Peary’s is down). The bright light of polar sensationalism all but blinded the world to Kane’s contributions.

Fergus Fleming, in his Ninety Degrees North: The Quest for the North Pole (2001), dismisses Kane as “not a great explorer.” Perhaps, but he was a great figure, a self-made hero with the echt American ability to whip up a popular frenzy and shape his own public image. He was also a fine writer, whose big book is an overlooked national treasure. Subsequent Penn grads have won renown, and others will do so in the future. But with major geographical features named after him on two different worlds, Elisha Kent Kane set a mark that may be impossible to beat.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is a contributing editor of The Washington Post Book World.