Take only memories, leave only footprints, and air-hug if you can.

By Barbra Shotel

A warning from friends, a mantra: “Travel now. We aren’t getting any younger.” Alaska topped my wish list. I envisioned a place as wondrous as the Grand Canyon, a place where one should “take only memories and leave only footprints.” There was a small problem. Traveling solo meant a pricey single supplement on an organized trip. Then Morton entered my life. No, it’s not what you think. Morton was not a man who swept me off my feet. It was an orthopedist’s diagnosis of a painful foot injury: Morton’s neuroma. Suddenly travel was not an option—at least not the kind that left a long trail of footprints. So after nearly two years in sensible shoes—no Manolo Blahniks for me—I booked a trip on a small ship that would navigate Alaska’s Inside Passage.

A New York Times article datelined “Sitka, Alaska” had caught my eye. Originally settled by Tlingit natives, the modern town was founded by Alexander Baranov as a Russian fur-trading post in 1804. At the height of its opulence, Sitka was known as “the Paris of the Pacific.” More recently, novelist Michael Chabon had used the town as a model for the fictional Jewish Alaskan homeland in his latest book, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union. According to the article, Chabon had spent time with a few of the thirty-odd Jewish residents who live among Sitka’s 8,947 souls. Surprised as I was that there were any Jews in this remote part of southeast Alaska, I was even more amazed to learn that one was a Hasidic lawyer and a transplanted Philadelphian. He had worked for the Sitka Native Tribal Bureau, co-authored Alaska Natives and American Laws, and—most stunning of all—his name was David Voluck.

I am a Philadelphian, I am a lawyer, I am Jewish. I knew a Philip Voluck growing up. In fact, I had a teenage crush on him. Could David Voluck be Philip’s nephew? Son? Had David been a student at Penn, I wondered? The whole thing reminded me of the 1990s television series Northern Exposure, whose main character was a transplanted New York Jew who practiced medicine in Cicely, a remote fictional Alaskan town. I was intrigued. I decided to phone David Voluck.

Yes, David told me, he went to Penn (C’92), and yes, Philip was his father. He offered to show me around Sitka—“Like I did with Michael,” he said, graciously putting me in the company of the prize-winning author. Before we hung up, David suggested that I call his father. I dialed the number right then, and Philip filled me in about his children and grandchildren, and David’s journey toward Hasidism. Better yet, he remembered me as soon as I told him my name.

Sitka was at the heart of a trip that confronted me with one breathtaking sight after another. In Denali National Park, rain brought out wildlife—grizzly bears and the requisite moose—but let up for a sun-drenched view of the largest peak in North America, which for most visitors is shrouded in clouds. The blue-iced wonders of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve were magnificent despite the glaciers’ continuing retreat, and Misty Fjords National Monument was a breathtaking, peaceful place whose glacially carved granite was indeed reminiscent of Yosemite and the Grand Canyon. But the highlight was the sublime image of three whales cavorting outside my breakfast porthole one morning at sea. As though choreographed by Rudolf Nureyev, the creatures dipped down and up again in impeccable unison, their tails coming out of the water in triplicate, highlighted by the brilliant early-morning sun.

Two days before our arrival in Sitka, I phoned David’s voicemail to confirm our meeting: 1:30 p.m. at the Back Door Café. But a last-minute schedule change put the ship into port five hours earlier than planned, at 8 a.m. Once I was there, a shopkeeper helped me find the Volucks’ home phone number, and David’s wife Esther answered when I called. “David is praying right now,” she said.

My heart sank. Then David picked up the phone. “Stay put,” he said. “I’ll come get you.”

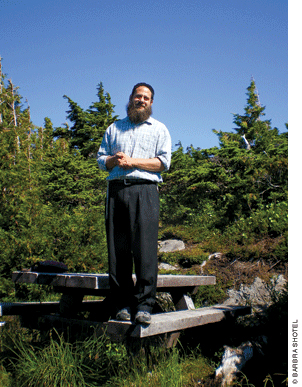

Bodily contact is discouraged between a Hasidic Jewish man and unrelated women, but when David approached me I still asked if I could shake his hand. He had a brown beard and the curly locks of his peyos were tucked behind his ears. He wore a button-down shirt over his traditional fringed garment, and a black skullcap topped his head. His reply was that of a natural politician. “We can shake hands if you feel it is necessary but preferably not,” he said, putting me perfectly at ease. Then, in lieu of the afternoon boat ride they had planned, he invited me to participate in Havdala, a ceremony blessing the new week.

If it weren’t for David and Esther, there would be no Hasidic Jews in Sitka. Yet it is possible that the reverse is also true—that if it weren’t for Sitka, David would never have followed the Orthodox path. Having begun his undergraduate years at Penn as a student of comparative religion, his interests ranged from African culture to the environment of the American West. During law school at Lewis & Clark College in Oregon, he took a summer internship working for the Sitka Tribe of Alaska. He returned to Alaska after graduating and eventually joined a small practice, which entailed flying to remote villages in small private planes to meet with tribal clients.

In an introspective moment, David told me that his clients would often remind him how important it was to them that they save their Alaskan heritage and culture. David would nod in agreement. He thought he understood, until one of the native elders made an unusual request of him after the tragic loss of her son. This woman wanted to “culturally adopt” David. In keeping with tradition, she had even selected a name for him to be used in the adoption ceremony—that of a deceased tribal chieftain. Then, in a dream, her deceased grandmother told her that David had his own tribe, and needed his own name. Only after hearing this was David struck with his own epiphany: that he should work to protect hisheritage and culture.

“Maybe it was meant to be,” he joked with me. “As a child I heard King David this and King David that as I sat in synagogue. I always thought they were talking about me.”

He decided to leave Alaska and study to be a rabbi. He met Esther in New Jersey, they married, and had a daughter named Nechama. But soon the financial sacrifice of rabbinical studies began to take a toll. David wanted to return to the law in Alaska, and Esther, who had grown up Orthodox in New York among eight siblings, left her family behind to follow him. I could not help thinking of my own decision at 34 to leave a top network TV job for a year living in New Zealand.

The reality of their newfound remoteness hit home during Esther’s second pregnancy. Birth complications culminated in an emergency airlift to Anchorage—an experience common to many Alaskans who live in small towns—where Esther remained in the hospital for 3 months. David carried on in Sitka as a single dad to their daughter, flying back and forth for visits while maintaining his law practice, consulting for a medical clinic, and hosting his bimonthly radio show.

David frequently encounters people who tell him, after being fooled by his beard into thinking he is Russian Orthodox, “I never met a Jew before.” But they may have listened to one. David’s show, broadcast from Sitka’s KCAW-FM, beams interviews and reggae throughout southeast Alaska. I was realizing that David was every bit the eclectic charmer that Philip Voluck had described to me.

“If Yehudah grows up to be a rap artist, he already has a name,” he went on, talking about his son, whose birth had ended up costing their health-insurance carrier some $240,000. “We call him Quarter-Mill. That would be his rap name.”

As we took in spectacular views from Tongass National Forest, David confided that he was reluctantly considering leaving Sitka for the Lower 48. His four-year-old daughter felt “fearless” in her current environment, but the rapid approach of the school years had put the issue of religious education on the family’s mind. The future may have a more urban place in store for them, somewhere a Hasidic lawyer can find work—“New York, Miami, who knows?”

In the meantime, being in Sitka with David Voluck was like walking down the street with a celebrity, constantly being stopped by his native Alaskan clients and other townspeople for a chat. If he were to stay, I told him, he would eventually end up mayor. “Probably,” he laughed with evident humility.

He may even have a way to win office without shaking hands. As we said our goodbyes, I felt I was leaving a dear friend. I told David I wished that I could hug him. He looked at me with a glint in his eye. “Well, we can, you know, air-hug,” he said.

“We do that all the time.”

Barbra Shotel CW’64 is a lawyer, freelance writer, and former network TV writer/producer.