Too Late to Talk

An ambitious, carefully constructed novel of family secrets.

By Virginia Fairweather

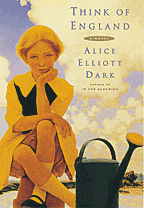

THINK OF ENGLAND

By Alice Elliott Dark C’76.

New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002. 272 pages; $24.00. Order this book

Alice Elliott Dark’s first novel begins with a stunning chapter. Nine year-old Jane MacLeod is awakened in the middle of the night by a violent scene between her parents. Their struggle has a sexually-charged subtext, but the child is too innocent to comprehend. Jane tries to intervene, and desperately assumes the blame for what precipitated the quarrel, a telephone taken off its receiver.

The parents, Via and Emlin, are engaged in a “brute tug of war” over the telephone, a flashpoint in their marriage. To Emlin, a doctor, its ring signals his responsibility to his patients. She cannot comprehend how he might care more “about strangers” than his family. Dark reveals their other battlefield. Earlier the same night, as the entire family sits together to watch the Beatles on television, Via entwines herself around Emlin. Later, the door to their bedroom closes—Jane hears the metal latch engage, and later, “a shout, bleak and full of anguish.”

The battle ends at 3 a.m. with an ultimatum; Emlin defies his wife to return to a patient, possibly unnecessarily. In a fury, the mother packs up all four children, and with her visiting brother, drives to their parents’ home nearby.

Dark’s craft is remarkable here. She tells a deeply disturbing story, sketching the prologue in swift strokes and creating complex characters, Jane and her parents, in very few words. She also makes the emotional bond between father and daughter very clear. The novel is ambitious and carefully constructed, incorporating some themes from Dark’s previous short story collections, Naked to the Waist and In the Gloaming [“Off the Shelf,” May/June 2000]—death, family discord, the ghosts of loved ones. The setting is Wynnemoor, a “charm on the bracelet of towns that surrounds Philadelphia.”

The book covers about 35 years in three bites. Jane is nine in 1964, when the opening chapter takes place. She is a “pretty” young woman just out of college and living in London, in 1979, in the second. Part three of the book recounts a family reunion in 2000. Midway in the middle section, Dark deftly drops the other shoe—we learn that Emlin died in an accident the night he left for the hospital. He never appears again, but his is the ghost Jane carries with her. Similarly, Via’s presence hovers over Jane though she is absent until the reunion denouement.

“Think of England” is a precept of Jane’s grandmother, with whom the MacLeod family live after their flight. Wynnemoor has “cool lawns and gardens, abundant roses, and bright winter berries.” People there know the difference between the Colonial Dames and the D.A.R. Dark doesn’t need to say more, and she doesn’t. The title phrase is a coda throughout the narrative, and much later, Jane calls it a “willful absenting of the soul at crucial moments, so that life consists only of what was comfortable.”

When Jane gets to London, she is living on her own, using her grandmother’s graduation gift, and wanting to write poetry. Almost immediately, she meets an offbeat couple, Nigel and Colette. Dark creates a striking character in Colette, a bold if not bizarre young woman.

The pair take Jane in, providing an eccentric education. Colette is American, wildly sophisticated and pragmatic, clearly a foil to innocent Jane, who knows about the Colonial Dames, but doesn’t know the meaning of a “beard,” even though Via’s brother, her Uncle Francis, is openly and comfortably homosexual.

Nigel is handsome, kind, charming, and aristocratic. He is also in need of a beard in order to receive a vast inheritance, and in a plot of Colette’s construction, she is the beard. Jane’s naiveté is such that she sees them as the “happy family” she lost. She is “tutored in beauty” by Colette, whose other courses include how to be imperious in restaurants and clubs, how to dress, and, most important, how to demand what you want in life. Jane’s emotional restraint is sorely challenged.

Nigel, like Jane, wants to write. His teacher is another American, Clay, with whom Jane has an affair. His emotional distance dwarfs Jane’s. His writing is everything, but she endures his priorities, suppressing her own wishes until challenged by Colette. Nigel and Colette’s relationship comes to an explosive end; Clay and Jane separate, and she heads home.

Dark shows the violence beneath Jane’s repression. When she and Colette witness an explosion, Jane thinks about her father’s “melting down to shards of bones and teeth” in his accident. When she was younger, she tried to think of the most horrific things she could imagine, to diminish her pain for her father’s loss. Colette and she go to (and quickly leave) a rock club in London, where mutual razor slashing is part of the scene.

The plot comes full-circle at the family reunion. Dark swiftly and sketchily re-introduces Jane’s siblings, then their progeny, and Via’s second husband. Jane is now a single parent with an 11-year-old daughter, Emily, who has her own ghost. She has nightmares about her twin, who died in the womb. Jane likens her daughter’s “survivor guilt” to her own.

No one in the family seems to like each other much, except for the children, and one wonders about Jane’s obsession with happy families. Her childhood manuscript, entitled “The Happy MacMillans” is given back to her at the reunion, with all its title irony. Jane is now an editor. Her personal life is focused totally on Emily. She’s given up on lovers, and Dark doesn’t mention friends. Jane apparently sees only her compassionate uncle Francis and Nigel. In another irony, the only happy family in the book is this homosexual pair.

Jane drops her “think of England mode,” and confronts her mother about the night of the accident. Via allows a few revelations, including the jealousy she felt over Emlin’s absorption in the infant Jane, but says “it’s too late now” to talk. We learn that Clay’s novel is a critical success. Jane writes him a summary note—“Just because you don’t see someone doesn’t mean you aren’t in their life.” Emlin’s ghost appears. He knows that in spite of her best efforts, Jane hadn’t been able to help him that final night. “I’m sorry,” she says. “It’s all right,” he says. End of book.

The plot bears a passing resemblance to Ian McEwan’s Atonement. Both begin with a young girl, a would-be writer, observing events that she misconstrues, and both end with a family reunion—two situations rife with possibilities. Think of England is a provocative and poignant novel, artfully written. Jane MacLeod’s melancholy pervades the book and haunts.

Virginia Fairweather wrote for the Gazette on the architect Wendy Evans Joseph C’77 in the November/December 2000 issue.

Whose Cyberspace?

The closing of the Internet frontier.

By James O’Donnell

THE FUTURE OF IDEAS:

The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World

By Lawrence Lessig C’83 W’83.

New York: Random House, 2001. 354 pp., $30.00. Order this book

We can’t talk about the Internet without metaphors. It’s a highway or it’s cyberspace, and we variously live and lurk there, surfing and chatting, meeting our significant others and doing business. That figurative language is well-suited for a virtual world, but it’s a sign as well that we do not yet know how to speak directly of the experiences we have in that space.

Making rules in a space and place so hard to talk about is a tricky business. Even knowing what the rules are and who has made them can be a matter of argument. In an earlier book, Code: and other laws of cyberspace, Lessig, who recently left Harvard Law School (after clerking for judge Richard Posner and Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia) for the edgier and more wired world of Stanford University, argued that the controlling forces in cyberspace are deeply programmed into the architecture and operation of the network. In this new and provocative book, he carries forward that argument with a freshened polemical thrust.

The heady early days of frontier Internet, he argues, have blinded us to the reality: the ranchers are moving in, fencing off the plains, dragging along behind them the lawyers and the schoolmarms and (given the acceleration of Internet time) the giant agribusiness conglomerates as well. The great landgrabs take many forms, and Lessig opposes all of them.

For example, in the news since this book was written, Lessig has succeeded in getting the Supreme Court to agree to hear the case of Eldred v. Ashcroft, in which an online publisher is contesting the constitutionality of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998. This act extends the term of copyright to the creator’s lifetime plus 70 years. In other words, as things stand now, Irving Berlin’s “Alexander’s Rag Time Band,” written in 1911, will be protected by copyright until the year 2059, and money will go to Irving Berlin’s estate every time it is played until then—unless the copyright term is extended still further.

On such terms, Elvis Presley has already made more money dead than he did in his entire working career, and the estates of other pop artists of the last half century will be equally fortunate. Winnie the Pooh saw the light of day in 1926 and A.A. Milne died in 1956; Disney purchased the copyright some years ago but saw that the silly old bear would go free to roam the Hundred Acre Wood in 2006—the new act keeps him penned up until 2026. The term of copyright has been frequently revised and extended in recent decades (every time Mickey Mouse is at risk of going out of copyright, Disneyphobes observe) with the effect that the extraordinary outpouring of creative work that has marked the post-WWII world shows signs of never going out of copyright.

Should we care? Lessig makes a powerful case that we should. He advances and refines in this book the notion of the “commons”—the property shared by the citizenry, property essential to common creativity. Public spaces, common utilities (like highways), and creative work in the public domain are all places where the creativity of a culture can exercise itself to good effect. The fundamental technical dimensions of the Internet were constructed precisely to create a free and open space in which such commonality of interests could meet and interact fruitfully. But as that freedom has shown signs of impinging on the economic interests of the great media corporations, they have reacted by looking for technical and legal ways to restrict the possibilities of the new media in order to protect their old income. The other panicky legal enactment of 1998, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, makes it frighteningly illegal to do anything (or even engage in theoretical research about doing anything) that might undermine technical devices created to restrict access to copyrighted materials.

Lessig is a pessimist in some important ways. Unless we act vigorously in the public fora—including the law courts—to oppose creeping protectionism, he argues, we will lose the freedom and opportunity that cyberspace offers. He stakes out a position that is neither “left” nor “right,” but libertarian and activist. An optimist in this space is one who holds that the power of the technical innovations already loose in the world is such that those who seek legal enactments to protect and restrict will in the end defeat themselves by their own cleverness and the energy of the culture will move elsewhere.

The optimists and pessimists share an important philosophical and societal issue. How far do we go in protecting the economic interests of individual and corporate members of the society? It can be argued that what’s good for Disney is good for America—jobs are created, money changes hands, and prosperity flourishes. But how far must we go to protect Disney? Will we look back 20 years from now and see the Disneys of this age in the way we now look back at the Welsh coal mines of a generation ago—industries that have outlived their usefulness? Will legal enactments designed to protect the old economy turn out to be a burden to the new that is finally shaken off, too late to help those they were meant to protect?

Against Lessig, I am an optimist, but would gladly share with him the sense that old and deeply entrenched ways of thinking about business and the mass media are unlikely to survive, and unlikely to go quietly. This year’s Penn graduates will live to see a world, I believe, in which both Disney and Microsoft have faded or disappeared. (Lessig’s book is published by Random House, once the cranky and creative offspring of Bennett Cerf, now a corporate wing of the German media conglomerate Bertelsmann. It’s still a free country.)

To focus on the “hot button” issues raised here is to do an injustice to this book. It is very much a partisan case in favor of a series of positions about the future of an information society, and deserves to be read, considered, and argued about, but it is surprisingly well written and lucid, and surprisingly comprehensive. If you have found the sound bites and newsmagazine tidbits about the controversies and possibilities of the Internet age hard to follow, this book includes not only polemic but extraordinarily clear and comprehensible accounts of how the Internet works, how it came to work the way it does, and what the issues and possibilities of the present and foreseeable future will be. Many will disagree with Lessig, but all can learn from him.

Until July 1, when he became provost of Georgetown University, Dr. James J. O’Donnell was professor of classical studies and vice provost for information systems and computing at Penn.

BRIEFLY NOTED

A selection of recent books by alumni and faculty, or otherwise of interest to the University community. Descriptions are compiled from information supplied by the authors and publishers.

QUENTIN FENTON HERTER III

Written by Amy MacDonald C’76.

Illustrated by Giselle Potter.

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. 30 pp., $16.00. Order this book

Quentin Fenton Herter III remembered always to say “Please,” to wash behind his ears and knees. He never ran but always walked, and sat quite still when grown-ups talked. But … Quentin Fenton has a shadow (named Quentin Fenton Herter Three). Never good and always bad, this Quentin loves to make a mess, break rules, and boss his friends. The two Quentins are careful to stay at arm’s length, but one afternoon, during a long, boring tea with “doilies, dust and aged ones,” each does something completely unexpected. Amy MacDonald has written a number of picture books in verse, including Rachel Fister’s Blister and Cousin Ruth’s Tooth. She lives in Falmouth, Maine.

THE COMPOSER-PIANISTS: Hamelin and The Eight

By Robert Rimm C’87.

Portland, Ore.: Amadeus Press, 2002. 340 pp., $29.95. Order this book

Robert Rimm writes about eight legendary, enigmatic, and interrelated composer-pianists of the instrument’s golden age and goes on to consider their present-day advocate and interpreter, Marc-André Hamelin. This book portrays The Eight—Alkan, Busoni, Feinberg, Godowsky, Medtner, Rachmaninov, Scriabin, and Sorabji—as “the piano’s aural sensualists” and explores the relationships of their music, their music-making, their ideas, and their lives. When, in 1996, Hamelin played a series of three recitals in New York featuring works of the very composer-pianists Rimm was researching, Rimm struck upon the idea of including him in this book; their collaboration took the form of a series of long interviews as well as a CD, Marc-André Hamelin Plays the Composer-Pianists. Rimm teaches piano and

keyboard performance, and music theory, composition and history at Chronos Studios.

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY AS SEEN THROUGH THE SPIRA COLLECTION

By S.F. Spira with Eaton S. Lothrop Jr. and Jonathan B. Spira C’83.

New York: Aperture, 2001. 232pp., $75.00. Order this book

From the very first dark rooms to the latest digital high-tech breakthroughs, the development of photography has changed the way in which Americans view their history and themselves. Looking through the prism of the Spira collection—a vast private assemblage of photographic equipment, images, books, and ephemera—this illustrated book chronicles photographic history as well as the emerging relationships between photography and other disciplines, such as painting, history, and the sciences. S.F. Spira, Eaton S. Lothrop, Jr., and Jonathan B. Spira—founder of the research firm Basex—lecture and write frequently on photographica and the history and future of technology.

THE YOUNG ATHLETE: A Sports Doctor’s Complete Guide for Parents

By Jordan D. Metzl, with Carol Shookhoff G’72 Gr’82.

New York: Little, Brown, 2002. 304 pp., $23.95. Order this book

Dr. Jordan D. Metzl, cofounder and medical director of the Sports Medicine Institute for Young Athletes in New York, fields many questions from parents on how to encourage safe sports play for their children. In response to the need for information of this kind, he has written—with Dr. Carol Shookhoff—a guide to everything from working with the coach to preventing and treating sports injuries. Shookhoff, who lives in New York, writes frequently on educational issues and is the mother of a teenage soccer player who also plays basketball and lacrosse, and runs track.

ECCENTRIC INDIVIDUALITY IN WILLIAM KOTZWINKLE’S THE FAT MAN, E.T., Doctor RAT, AND OTHER WORKS OF FICTION AND FANTASY

By Leon Lewis G’62.

Lampeter, Wales: Edwin Mellon Press, 2002. 188 pp., $79.95. Order this book

This is the first full-length, critical study discussing at length all of the most ambitious novels of William Kotzwinkle. In addition to analytical examinations of his most prominent works, including The Fan Man and his adaptation of the film E.T., the book identifies patterns of coherence, recurring themes and subjects, and strategies of comic invention. Dr. Leon Lewis, an English professor at Appalachian State University, is the author of Henry Miller: The Major Writings and numerous articles on contemporary American and British writers.

SHAKESPEARE ON THE AMERICAN YIDDISH STAGE

By Joel Berkowitz C’87.

Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2002. 304pp., $32.95 (cloth). Order this book

By the early 1890s, New York was fast becoming the world’s center for Yiddish theater. And America’s Yiddish actors—living on Second Avenue and Manhattan’s Bowery—were wild about Shakespeare. This book constructs the history of this unique theatrical culture by focusing on the 1892 production of The Jewish King Lear and Yiddish versions of The Merchant of Venice, Hamlet, Othello, and Romeo and Juliet. Joel Berkowitz is assistant professor of modern Jewish studies at SUNY Albany.

VOYAGE THROUGH TIME: Walks of Life to the Nobel Prize

By Ahmed Zewail Gr’74 Hon’97.

Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2002. 288 pp., $22.95. Order this book

The discovery of the femtosecond—one quadrillionth of a second—has meant new ways of viewing molecular landscapes for scientists around the world. It has also meant, for the author, an unshared Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1999. Born in an Egyptian delta town, Dr. Ahmed Zewail chronicles the story of his personal life alongside the scientific achievements that took him to California and culminated in his invention of a laser camera to capture events in the split-second world of femtochemistry. Zewail is the Linus Pauling Chair of Chemistry and professor of physics at Caltech and director of the National Science Foundation’s Laboratory of Molecular Sciences. He was awarded the Grand Collar of the Nile, Egypt’s highest state honor.

WEST PHILADELPHIA: University City to 52nd Street

By Robert Morris Skaler Ar’59.

Portsmouth, N.H.: Arcadia, 2002. 128 pp., $19.99. Order this book

In the first half of the 19th century, West Philadelphia consisted of farmland and virgin stands of timber. The area soon became home to wealthy businessmen who built elegant mansions and villas in University City and Powelton Village. West Philadelphia’s growth accelerated northward into Belmont and Parkside-Girard after the 1876 Centennial Exposition and westward into Cedar Park, Spruce Hill, and Walnut Hill in the 1890s with the introduction of electric trolley lines. This is the first photographic history of the area in the last 100 years. Images of modest West Philadelphia rowhouses, which slowly took over the open farmland after the Market Street Elevated opened in 1907, illustrate why Philadelphia became known as the “City of Homes.” Rarely seen photographs of the streets where people lived and worked fill this history. Robert Morris Skaler is a forensic architect and historian who has been collecting historic images of West Philadelphia for more than 35 years.

WINNING WOMEN’S VOTES: Propaganda and Politics in Weimar Germany

By Julia Sneeringer Gr’95.

Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. $27.50.

Order this book

In November 1918, German women gained the right to vote. Suddenly, a deluge of written and visual propaganda addressing motherhood, fashion, religion, and abortion appeared, as campaigns for female support ignited across the political spectrum. This book documents the ways in which propaganda—aimed at women by parties from Communist, to Catholic, to Nazi—sought to reconcile traditional assumptions about women with their new stance as voters. Dr. Julia Sneeringer is associate professor of history at Beloit College in Wisconsin.

SOLD TO THE HIGHEST BIDDER: The Presidency from Dwight D. Eisenhower to George W. Bush

By Daniel M. Friedenberg W’43.

Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 2002. 315 pp., $29.00. Order this book

A broad indictment of the American presidency, this book laments the vast influence of money on elections and subsequent policies of all the occupants of the White House since Eisenhower. After detailing what he terms the “legalized corruption” of the American electoral system, Daniel Friedenberg calls for a series of reforms, including the use of new technology to create a more equitable future. He is president of John-Platt Enterprises, Inc., a New York general investment company.

WINNING DECISIONS: Getting it Right the First Time

By J. Edward Russo and Paul J.H. Schoemaker WG’74 Gr’77.

New York: Doubleday, 2001. 352pp., $27.50. Order this book

High-speed decision making in the business world can be stressful, haphazard, and often unavoidable. This book attempts to pin down rapid thinking to a teachable, four-step science. Based on the authors’ 30 years of decision coaching at the University of Chicago’s Center for Decision Research, it uses worksheets, questionnaires, and case studies to teach business professionals how to make intelligent decisions in an atmosphere of uncertainty. Dr. Paul J.H. Schoemaker is the founder, chair, and CEO of Decision Strategies International, Inc. and research director for the Emerging Technology Management Research Program at the Wharton School.

OCCASIONAL GLORY: A History of the Philadelphia Phillies

By David M. Jordan L’59.

Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2002. 296 pp., $29.95. Order this book

The Philadelphia Phillies have lost more games and finished in last place more times than any other Major League club. The lost seasons have established their reputation as one of the most unsuccessful teams ever to take the field—but even so, the Phillies have had some unforgettable players and notable triumphs. This work is a history of the baseball club from its inception in 1883, when the Worcester (Mass.) Brown Stockings moved to Philadelphia, through the 2000 season. David Jordan, an attorney, is also the author of The Athletics of Philadelphia: Connie Mack’s White Elephants, 1901-1954 and president of the Philadelphia A’s Historical Society.

A DUEL OF GIANTS: Bismarck, Napoleon III, and the Origins of the Franco-Prussian War

By David Wetzel C’70.

Madison, Wisc: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2001. 240 pp., $24.95. Order this book

The clash of two extraordinary personalities—Otto von Bismarck and Napoleon II—drives this account of the events leading up to the Franco-Prussian War. Historian Dr. David Wetzel tells how this utterly avoidable war that unfolded in the brief, eventful days of July 1870 ushered in an era of power politics that would reach its apocalyptic climax in World War I. Wetzel, also author of The Diplomacy of the Crimean War, works in the administration of the University of California, Berkeley.

THE ACUPUNCTURE RESPONSE

By Glenn S. Rothfeld C’ 71 and Suzanne Levert.

New York: McGraw Hill, 2001. 256 pp., $14.95. Order this book

Reported to treat and prevent a host of illnesses, acupuncture has gained acceptance in this country in recent years; in response, this book aims to make acupuncture even more accessible. Providing advice on everything from the first visit to an acupuncturist to identifying the most easily treated diseases, the author explains this ancient system of medicine from a Western point of view. A clinical assistant professor at Tufts University School of Medicine, Dr. Glenn S. Rothfeld is also medical director of WholeHealth New England, Inc.

“Before Us, They Were Here”

White Dog. New Deck. The Palladium. Steinberg-Dietrich. Rachel Solar-Tuttle C’92 L’95 does more than a little name-dropping in her first novel, Number Six Fumbles. Set at Penn in the early 1990s, her story follows a high-achieving, sociable sophomore, who, after watching a home football game against Cornell, starts to wonder what would happen if she “fumbled the ball” in her own life:

There are these photographs of athletes that line the walls of Smokes. To me they stand for the people who came before. Before Us, they were here. They were an Us. I hate to think of that, of the relentless way time keeps coming at you, especially at school where they march in a whole other class to replace you as soon as you graduate.

“These pictures give me the creeps,” Phoebe says, looking at a grainy black-and-white photograph of a guy in an old-fashioned sports costume, posed on a single knee with a medicine ball. It’s feathered at the edges.

But that’s not the one that stands out to me. “What about this one?” I say. It’s a head shot, just above our booth. He’s so handsome, but standoffish, it makes you almost have to brace yourself to look at him, makes you suck in air without thinking. His eyes have a sharpness that even in black and white says blue to me; his dark hair, cut in a flattop, emphasizes the squared jaw, the high cheekbones. I’ve thought about him at random times before, wondering who he is and why that picture was taken and what he’s thinking about.

He probably drove his red-orange MG down Locust Walk to his Young Democrats meeting, his Friars Club meeting, squash practice. He breezed through the same halls we do, sang the same songs on the football field.

“It feels like he’s listening to us, does that seem crazy?” I say. “We’re sitting here waiting for more drinks, watching the hookups and the little fights, everything that’s going to be gossip tomorrow. We’re sitting here letting more and more time go by, and his time is over. It’s as if he’s saying, ‘Look at me; look at the person I was once. All those moments slipped away so fast. If you’re not careful, you become someone you never intended to be. And you can’t go back.’ —Hey, Phoebe, where’s your book bag?”

She pulls the bag from under her seat.

“Can I borrow some paper?”

Phoebe takes out a spiral notebook, rips out a bunch of pages, and hands them to me. I pass some back to her. I reach in her bag for two pens and start drawing stick figures and smiley faces on all of the pages. Phoebe does too. Then I stand on the seat, reach over, and start covering up the photographs, one by one, pressing the ripped edges of the paper around the frames. No one seems to notice. I save the best for last and do it carefully and with relish, covering up those blue eyes, the eyes that see too much, know too much about all of our futures.

—Excerpted from Number 6 Fumbles by Rachel Solar-Tuttle, Pocket Books/Simon & Schuster, 2002.